Amerika’s box

by Mai Al-Nakib

“The most original first collection of short fiction I have read in years.” A. Manette Ansay

The decision to change their five-year-old daughter’s name was a bold one for Ahmed and Fatma to make. Kuwait was, after all, a country tangled in red tape. But like most of their fellow citizens in the year 1991, Ahmed and Fatma wanted to commemorate their nation’s gratitude to America. Fatma was in her late forties. It had been a few years since she was last pregnant. They knew something drastic had to be done, so they ploughed patiently through daunting name change procedures. They submitted pillars of forms to the proper ministries. Small bundles of cash slipped quietly under desks. They publicized their young daughter’s new name in two newspapers. Once the paperwork was done, Ahmed and Fatma informed friends and family of the change and invited everyone to their home to celebrate over istikans of saffron tea. Men in one room, women in the other, eating like locusts and singing along to music. They were free once again, safe together in the long afternoon.

Ahmed and Fatma were not wealthy. They lived in government housing near a gas station in the city center. Ahmed pushed paper in a ministry job that masked unemployment. Fatma stayed at home, swamped with the details of domesticity. Their decision to have eight children was largely economic. While both had an uneasy sense that birth control, like a gynecological exam, was against Islam, it was mostly for the per-child social allowance that they had permitted their family to grow. Each newborn added fifty dinars a month to Ahmed’s paltry salary. Fifty times eight could not be passed up, so Fatma had spent most of her adult life ballooned by babies.

With every pregnancy, Fatma prayed for a girl. A daughter to follow in her footsteps and to help with chores. A daughter to share the burden of her disappointments, to scold and to love. A daughter to plan a wedding for, to take care of her and her husband in their old age. None of the first seven pregnancies answered her prayers. By the eighth she had stopped asking, accepting that the girls she would choose for her sons to marry would be as close to daughters as she was going to get. Her baby girl’s unasked for arrival was, to Fatma, a sign of Allah’s subtle endorsement of her years of du‘aa. To Ahmed, his daughter was, more simply, a reason to soften, a way to escape the noose of habit.

In elementary school, Amerika felt special. Nobody else had her name. She didn’t know what exactly America was then. All she knew was that whenever she told people her name it made them exuberant. To begin with.”

Young Amerika Ahmed Al-Ahmed took to her new name instantly. The oily gray man in charge of stamping name change forms had mistakenly replaced the c in America with a k. He had picked up snippets of English here and there, and America sounded to him like it should have a k in it. In any case, he was starving and wanted to leave work early for lunch. He had no time to look into trivialities. By the time Ahmed was informed by the oily gray man in charge of receiving name change forms that America was spelled with a c not a k, it was too late. If Ahmed wanted to change that single letter, he would have to wait until after the weekend and pray for the unlikelihood that both oily gray men showed up for work. Ahmed made the wise decision to accept the k; it didn’t really matter since his daughter’s name would be written mostly in Arabic. As it turned out, Amerika would come to love her accidental k especially. A k like a kick in the air, like a Radio City Rockette.

In elementary school, Amerika felt special. Nobody else had her name. She didn’t know what exactly America was then. All she knew was that whenever she told people her name it made them exuberant. “Yes! We should be grateful. If it weren’t for America, we would be part of Iraq, Allah la yagooleh. You will never forget to be thankful to America. Neither should we.” Always the exuberance. To begin with.

The only person in those early years who responded differently to Amerika’s name was her religion teacher. Abla Nada was tightly wound, a pinprick of a woman, with a face as thick as coffee. Her head was securely bandaged in black, a hijab covering her hair, her forehead down to her eyebrows, half her cheeks, and most of her chin. As she spoke, her saliva sprayed onto open books, shiny desks, the tops of students’ heads, the blackboard. “An infelicitous name for an infelicitous little girl. You are doomed, my dear. With a name like that, there will be no redemption for you. Nor for any of us who dare to step across Allah’s line. In your graves, you all will hear the footsteps of your mourners walking away, leaving you alone. Your punishment will begin as your grave starts to shrink around you and you feel the hot breath of hell encircle your body, you smell its rot, its pus, its blood and urine.” Saucer-eyed children listened in terror, unable to close their ears or their hearts to her words. Only Amerika seemed immune. She listened to Abla Nada’s tales of torture and punishment like she would ghost stories around a campfire. She scooped up her teacher’s chatter as she did her grandmother’s about what it was like to grow up in the desert, about how the skies used to be a shattering blue that reminded you to be grateful for beauty and birds. Abla Nada’s accounts were stories and Amerika loved stories. Her friends left class trembling, crying, promising to pray. Amerika left with a kick of the heels, a Rockette, a rocket, the letter k in search of adventure.

Amerika pronounced her name ‘Amreeka’, with a stress on the r not the m, because that’s how America is pronounced in Arabic. She had no idea that it was pronounced differently in other places, at least not till she was about seven and started watching satellite TV. Then she learned it could also be pronounced ‘Ammurrika’ or ‘Amereek’. She discovered her name was a place, a big place with tall buildings and wide open spaces and violent storms with lots of rain and snow. She learned about icicles that clung to the branches of trees like crystal fingers. About trees with leaves that changed color, bursting into orange and red, yellow ocher and chestnut brown. She found out about Halloween and dressing up in scary costumes. She thought Abla Nada might enjoy the idea of Halloween, obsessed as she was with the shape and smell of death, but Abla Nada told Amerika in no uncertain terms that she would be sent straight to hell simply for knowing about such things. Amerika retorted that if hell was anything like Halloween, full of trick-or-treating and jack-o’-lanterns, she would gladly go.

Amerika learned about baseball, hitting a white ball with a stick and running and spitting on the ground. About Babe Ruth, left-handed hero. About cowboys and horses, mother-of-pearl buttons on flower-embroidered, close-fitting shirts. About skies like fields that turned yellow and green before a storm, clouds that colored the mountains black and blue, and funnels that came down and destroyed hundreds of homes, decimated lives and left sad old photographs floating in the aftermath, carried by a remnant wind.

Amerika discovered New York City, a cathedral of a place, gray and glittery, with a park in the middle of it, a lake in the middle of the park, and a woman standing tall in the ocean. Everything exciting happened in New York. It was a maze of crime and food sold on street corners. It had numbered avenues with square intersections and yellow taxicabs. Intersections in Kuwait were round, taxis orange. Manhattan was an island, like the Kuwaiti island of Failaka, though, unlike Failaka, Alexander the Great had never been there. Alexander had named Failaka ‘Icarus’, after a son who flew too close to the sun.

The grandest thing Amerika learned was the language. Not just English… American. She rolled her tongue around its rs like a parrot, owned its nasal crescendos and punchy confidence. American pried opened a world of wonder for Amerika.

…

Watching American television via satellite over the years, Amerika came to believe people laughed more in that vast place that stretched further than it seemed possible to stretch – from sea to shining sea. To contain this vastness, this remarkable joy, to make it hers, Amerika decided when she was ten to keep a box, to fill it with as much of America as she possibly could. Amerika knew she had the propensity to collect like a magpie, so she decided to limit the size of her box. A wooden box, about ten inches squared, with a hinged lid. Inside, the box was divided into twenty-five compartments, each two inches by two inches. She had insisted on going to see the carpenter herself, to the amusement of both the carpenter and her father. She didn’t want the box to be too heavy, but it had to be sturdy. The lid was to have a lock in the middle and the key had to be made of brass.

Designing the box was the easy part. Figuring out what twenty-five objects to put into the box was much harder, and they would vary over the years. At ten, Amerika filled her compartments with: the wrapper of a Baby Ruth bar (her uncle had brought her back a bag of candy from Florida); green jellybeans; grape Bubble Yum; five different colored cat’s-eye marbles (she had seen television kids in a schoolyard flicking them during recess); a small American flag on a toothpick; a clam shell (for clambakes); a wooden Santa; peanuts (for peanut butter, which, she learned, should be eaten on soft white Wonder Bread with the crusts cut off and strawberry or grape jelly not jam); a folded page ripped out of an Archie comic; a teensy teepee she got out of a Kinder Egg (not sold in America but usually containing stuff to do with America); a John Wetteland baseball card (1996 World Series MVP); an Elvis pin; an orange maple leaf cut out of felt; a short string of popcorn; Fruit Loops (she loved the curve and stretch of the word ‘loop’); an Abraham Lincoln penny; a yellow HB2 wood pencil (sharpened down to almost nothing, pink eraser intact); a small silver figurine of the Empire State Building; a Coke bottle cap; a McDonald’s cheeseburger wrapper (after liberation, the biggest McDonald’s in the world rose like a neon castle on the Gulf Road); a foot of dental floss; a falcon’s feather as a stand-in for a bald eagle’s (brought back from the brink of extinction, symbol of national pride); a Fisher Price Little People pilot with a round brown head on a blue plastic body (finding out about slavery would rupture somewhat Amerika’s faith in American joy); and a Winnie-the-Pooh sticker. Amerika filed the final compartment on the lower right hand corner with American idioms written neatly on strips and scraps of paper. She wrote with tiny handwriting so that she could fit as many as possible in the two-by-two space:

ass in a sling

at first blush

between the devil and the deep blue sea

by the seat of one’s pants

cock-and-bull story

fat of the land

flat as a pancake

for Pete’s sake

get down to brass tacks

hard as nails

Indian summer

in the twinkling of an eye

into thin air

laughed my head off

lickety-split

lit up like a Christmas tree

lump in my throat

many moons ago

out of the blue

paint the town red

pooped out

scream bloody murder

sell snow to the Eskimos

square peg in a round hole

stars in your eyes

under my skin

the world is your oyster

zip it

This compartment was Amerika’s favorite, and it was always stuffed to capacity. She had decided at the very beginning that whatever came out of the box had to be thrown away before a new object was added, but she couldn’t bring herself to throw away the idioms. If she wanted to add a new idiom to an already full compartment, she would carefully choose one to remove. The only condition she set herself was that the first letter of the removed idiom had to match the first letter of the idiom to be newly inserted. So, for example, if she wanted to add “mad as a hornet” to a full compartment, “many moons ago” had to be removed. Once retired, old idioms, organized alphabetically, were placed in a great black stamp album that looked like a witch’s spell book. Amerika liked the crinkling sound of the white protective tissues between the heavy pages. She adored the way her scraps looked, odd sizes and textures, splayed against the black. She would come to love that book almost more than the box.

Amerika never took her box with her to school, though she spent most of her time there thinking about it. School had become a nightmare for Amerika. The gulf between her life at home, comfortably padded with satellite TV and, soon enough, the Internet, and her life at school, where teachers like Abla Nada were multiplying like spiders, was becoming intolerable. Because she was the youngest, the most cherished, the long-awaited, her parents left her to her own devices. They were impressed with her sponging up of English – “Not just any English,” she would boast to them, “American English!” – with her ability to entertain herself for hours, and with her commitment to her special projects, baffling as these sometimes were to them.

Students were discouraged from reading anything other than the Qur’an. But Amerika felt instinctively that reading was a chance to imagine new worlds in words.”

Amerika loved to read. Nobody in her family ever picked up a book if they didn’t have to, and they never had to. The idea of reading a novel or poetry or anything other than the newspaper wouldn’t have occurred to them. Amerika didn’t learn the habit at school either. Students were discouraged from reading anything other than the Qur’an. But Amerika felt instinctively that reading was a chance to imagine new worlds in words. It was a way to create chinks in walls where they weren’t supposed to be. She had figured out on her own that the only way she was really going to learn English was by reading books in the language. She loved Beverly Cleary, Louise Fitzhugh, Judy Blume. She saw herself in Harriet the Spy, Sheila the Great, and Nancy Drew. She begged her older brothers to drive her again and again to the Family Bookshop in Salmiya. They always did.

Amerika’s seven older brothers didn’t want to impose their will upon their little sister. She was delightful in her smallness, a jack-in-the-box in the middle of their nothing-special lives. They teased her about her America obsession, about her book fixation, about being a girl and being the youngest, but they did not tell her what to do or what to think. She knew, from stories friends told her about their own brothers, that hers were exceptional. At first her mother had wanted to mold her daughter, the way she had been molded by her mother, into a baby-making shape that could balloon and grow but not fly into the sky like a bird or a kite. But Fatma quickly decided she would rather Amerika take shape on her own and make her own shapes in turn. Maybe it was because she was her only daughter, her final child in a line of children, the one she hadn’t prayed for but who had answered her prayers. Fatma was taking a risk, making a quiet decision to allow something she could not predict to happen. Amerika was as grateful as honey for her mother’s arms around her, for her brothers, for her Mr Rogers in a dishdasha father, for the way things were at home. It made her life at school tolerable, but only just.

By the time Amerika turned fourteen, every single girl in her class at the all-girls government school was a mutahajiba. Their heads were covered up, swaddled, one by one. A child would pop her newly wrapped head into the classroom and all the other girls would rush over to kiss and congratulate her, to ask what had made her come to her senses. “I dreamed of a serpent coiled around my thighs and felt its teeth sinking into my skin. I woke up crying, and my mother said it was Allah’s way of reminding me that my uncovered hair was a sin. She’s right. It’s my turn.” Many of the girls didn’t have a choice. At ten or eleven their parents forced them to wear the veil, their little heads covered in darkness, their mermaid hair out of the light forever. Some girls covered up because everyone else was doing it. They gave in to the pressure like television teenagers gave in to smoking in bathrooms or unprotected sex. Others did it because they believed it would pave the way for marriage. They imagined dark eyes appreciatively surveying the iconic bit of cloth. These girls glided through the air, their pert bodies draped in multicolored chiffons sparkling with sequins. Still others, with the sharp cheddar fervor of true believers, covered their entire faces in black, a new, creepier breed of niqab. And the niqab – permitting only sullen eyes to peep through curtains of black – was suddenly everywhere.

By the time Amerika turned fourteen, every single girl in her class at the all-girls government school was a mutahajiba. Their heads were covered up, swaddled, one by one. A child would pop her newly wrapped head into the classroom and all the other girls would rush over to kiss and congratulate her, to ask what had made her come to her senses. “I dreamed of a serpent coiled around my thighs and felt its teeth sinking into my skin. I woke up crying, and my mother said it was Allah’s way of reminding me that my uncovered hair was a sin. She’s right. It’s my turn.” Many of the girls didn’t have a choice. At ten or eleven their parents forced them to wear the veil, their little heads covered in darkness, their mermaid hair out of the light forever. Some girls covered up because everyone else was doing it. They gave in to the pressure like television teenagers gave in to smoking in bathrooms or unprotected sex. Others did it because they believed it would pave the way for marriage. They imagined dark eyes appreciatively surveying the iconic bit of cloth. These girls glided through the air, their pert bodies draped in multicolored chiffons sparkling with sequins. Still others, with the sharp cheddar fervor of true believers, covered their entire faces in black, a new, creepier breed of niqab. And the niqab – permitting only sullen eyes to peep through curtains of black – was suddenly everywhere.

Amerika’s mother told her that before the invasion munaqqabas were rare. They could be found mainly around the outskirts of the city or in the desert where the Bedouins lived. “But after liberation, ya habibti, Kuwaitis seem to have caught the virus.” Amerika’s mother wore a black abaya like a magician’s cape around her shoulders when she went to the souk or to visit friends. She was not veiled because she said it was not the old Kuwaiti way, at least not the way it was when she was growing up. “Kuwaiti women were modest but they were not mice, Amerika. We were never mice.” Amerika would jump up and down on her mother’s bed and yell, “We are not mice! We are not mice! I am not a mouse! I REFUSE TO BE A MOUSE!” Amerika’s hair was as lovely as her mother’s, rich mahogany waves lapping her shoulders. There was no way she was ever going to cover it up. Her hair was her. It was her mother’s loop of love G owing, and she refused to hide it away.

Amerika’s obstinacy meant she had to deal every day with the acid gaze of teachers and the cruelty of classmates. Suffering years of their relentless pestering was draining, sometimes almost more than Amerika could bear. She put up with it because she knew in four years it would all come to an end. In four years she would finish secondary school and go to university. She would be the first in her family to do so. She would study English literature and it would set her free. That dream, along with satellite TV and her beloved books, kept Amerika going. She would have wanted her teenage years to mirror Betty and Veronica’s. Going to the movies on a date, pool parties and bonfires on the beach, spin the bottle and first base, chili fries and root beer floats with her best friends forever on Saturday afternoons. She would have wanted the Macy’s Day Parade and touch football on a nippy fall day. Footloose and fancy free, fun in the sun, and the devil take the hindmost. That would never be hers. Still, she knew she had more than most, so she put up with her solitude and with the bitterness of others. She put up with it because she had her box to put it into.

Amerika’s box was for the extras, for the not quite rights but the wanting it anyways. Every desire to and yearning for was there. Some objects remained in compartments for months, even years. In other compartments there was a tornado of changes. From a red Lifesaver, to a snippet of jeans, to a cherry-flavored condom virtually overnight. She played her box like a virtuoso musician, fingers flying across compartments, folding, unfolding, arranging, rearranging, sliding in, pulling out, ceaselessly. She spent hours hunched over it, examining it from every angle, carefully considering what belonged beside what and for how long. The hours of the day she was away from it, she was thinking about it, drawing maps, making lists. Her maps looked like constellation charts, her lists like clever haikus. Amerika’s box was her escape, her window opening when the doors, one by one, were clicking shut.

…

When the buildings came down, everything changed. Suddenly it was no longer Amerika and America together. Now it was the Axis of Evil and terror under every rock; it was us and them and never the two shall meet. Amerika was, lickety-split, completely alone. Her name, no longer exuberance to others, often triggered fury and furrowed brows. Her box had been her portal to elsewhere, her string of idioms a fishing line to an alternative pond, bigger and better. Instead of marriage and children, instead of a dead-end job at a ministry or bank, instead of segregated tea parties, her box and her album were travel and ambition, optimism and go-getting, mountain climbing and paragliding. But after the buildings came down, Amerika slowly turned into a half-knit sweater unraveling. She started to come undone like the laces of bright white Converse hi-tops. To stop the weighted stones, the magnet pull, Amerika began to collect buttons for the compartment where three Tootsie Rolls used to be. Ghost white buttons. Misty rose and dim gray buttons. Firebrick red and burnt sienna buttons. Buttons of pale flesh. Buttons for empty spaces, for something missing, for reaching outward and spreading she wasn’t quite sure what or where to anymore. Her search for the right color buttons held things in check for a while, through secondary school, until she turned seventeen and heard about the ring of fire around Baghdad.

When the buildings came down, everything changed. Suddenly it was no longer Amerika and America together. Now it was the Axis of Evil and terror under every rock; it was us and them and never the two shall meet. Amerika was, lickety-split, completely alone. Her name, no longer exuberance to others, often triggered fury and furrowed brows. Her box had been her portal to elsewhere, her string of idioms a fishing line to an alternative pond, bigger and better. Instead of marriage and children, instead of a dead-end job at a ministry or bank, instead of segregated tea parties, her box and her album were travel and ambition, optimism and go-getting, mountain climbing and paragliding. But after the buildings came down, Amerika slowly turned into a half-knit sweater unraveling. She started to come undone like the laces of bright white Converse hi-tops. To stop the weighted stones, the magnet pull, Amerika began to collect buttons for the compartment where three Tootsie Rolls used to be. Ghost white buttons. Misty rose and dim gray buttons. Firebrick red and burnt sienna buttons. Buttons of pale flesh. Buttons for empty spaces, for something missing, for reaching outward and spreading she wasn’t quite sure what or where to anymore. Her search for the right color buttons held things in check for a while, through secondary school, until she turned seventeen and heard about the ring of fire around Baghdad.

Iraq was the other side of Amerika. It was as much for Iraq as for America that Amerika was named, though in a different direction, away from rather than toward, despite rather than because of. Growing up, she hadn’t given much thought to Iraq, to Iraqis. Saddam Hussein was the bogeyman lurking under the bed with spindly green fingers waiting to grab unsuspecting ankles. But Saddam was not death to Amerika. He was no longer a threat, no longer armies marching in, tanks rolling down the Fifth Ring Road, hellfires burning. He was no longer bullets in brains and homes gutted, at least not for Amerika. She didn’t know Saddam had made her father cry for the first time in his adult life, had made her mother get down on creaky knees to take her husband’s head in her hands, to smooth away foreign tears, to knead hard the strangeness of being taken over, gulped up in a day. Ahmed and Fatma wanted to spare her, their little sprout, the memory of loss, the skeleton of fear. But it was in her name, hollered impatiently, whispered with concern. Iraq was in Amerika. Saddam was there. Fear was there. Her name was the maze of memory, an ant threading a shell, around and around. It was loss – deep, sharp cuts into the bodies of fish, waxy feathers melting in the sun.

When Amerika thought about her box, she felt her body free, uncovered. She dreamed of belonging to herself, of being alone and not being afraid to be alone. She imagined what it would feel like to glow.”

Amerika had always felt her life unfolding like her box. Amerika was a virgin but she didn’t want to be. She wanted to feel herself glistening and unfolding in someone’s arms. When she thought about sex, she saw herself in an airplane or at an airport. She saw LAX or JFK or O’Hare, sometimes even Fiumicino or Charles de Gaulle. She saw her box in her arms and a JanSport slung across her back. When Amerika thought about her box, she felt her body free, uncovered. She dreamed of belonging to herself, of being alone and not being afraid to be alone. She imagined what it would feel like to glow. At seventeen, Amerika was ready for something to happen to her, to her body, to her box. When she felt herself being pushed into the Axis of Evil, into the center of its wicked triangle, despised, spat upon, after all this time, she made the decision to wait. This was not her moment. She forced her body to recoil back into its shell, no ant circling and threading with ingenuity, with care. She stopped anticipating the smell of the Atlantic. She had begun to see in America her direction home, from sea to shining sea. But it was spitting her out now. She had to pause it all, to stop before everything came undone, before it all unraveled to nothing. Amerika waited with bated breath.

Then the war came. Not her war exactly. Not her country’s war. Not exactly, but inexactly it was hers, her country’s too. Here it was, the stones weighing down, and her body, pure as the moment before flight, never to be her own. Kuwaitis were told to stay inside, to seal the windows with duct tape and plastic; it was too late for gas masks. There would be a symphony of sirens, a swell of sound, and then a mad scramble into the safe room, sweating, gasping, thirsty. Dodging Scuds for America, Scuds from Iraq. Once, twice, three times Amerika and her family scrambled, crammed together like dates in a crate, and then her father, Ahmed, decided to ignore the wailing, to stay put because he was fed up. Enough was enough. He wanted to eat, to pray, to sleep in peace.

During the sirens, they stared together at the TV screen, at a flashing “Danger Ongoing” and then, improbably, at Bugs Bunny screeching, “Of course you realize, dis means war!” They heard CNN announce: “Decapitation Strike.” They heard: “Shock and Awe.” They heard: “Lit Oil Wells in the South” and “A Circle of Fire.”

Amerika spent most of those first few days of the war in her bedroom, stretched out as wide and open as possible on her bed, listening to the sirens sounding endlessly, majestically, one after the other, then the all clear. Time felt suspended, attenuated, an inchworm and a cougar. She kept her box and album beside her, not wanting to forget, not wanting to allow the wailing to blot out everything else. She thought of Acapulco gold and being lit up like a Christmas tree. She wanted to remember laughing her head off and the world as her oyster.

…

On the ninth night of the war, Amerika decides to go for a walk. There is an imposed curfew, she knows there is. She waits until each member of her family falls asleep one by one (like candles blown out after the kind of party her parents had never hosted, would never host, but that she dreams of hosting one day, welcoming her guests in a silver dress), then goes out anyway. She walks into the night where everything, in its velvetiness, seems possible still. The roads are automatic walkways, the empty country, never before so empty, an airport, a promise of something else, outside the Axis, outside war and vitriol and falling down, down, down with melted, exhausted wings. She walks out in a blue pleated skirt and gray V-neck sweater, her box in her outstretched arms. The album stays behind, the scraps of idioms breadcrumbs home. The country is still, fossilized in the amber light of streetlamps. It is cold, the end of March, desert temperature extremes. She wanders down the lonely walkways, pulled by a magnet. She heads toward the edge of the city, toward the devil and the deep blue sea. Police cars float by and, once, a chemical weapons detector truck with equipment on the flatbed – jerky rotations, colored lights beeping – tasting the air.

Nobody sees Amerika. Nobody is looking for a girl in the dark with a box and a red scarf around her neck. She pushes on, not really thinking but moving, feeling her body ebbing seaward. She stops at a slice of beach, rocks piled up, a concrete pier. She arrives at a sliver of what it used to be before McDonald’s rose upon the broken coast. She dances along the shore, tries to imagine it long once again. She pictures Icarus, Alexander’s island, whole, afloat on phosphorescent blue, haloed with snow white waves, a place before sons fell.

Nobody sees Amerika. Nobody is looking for a girl in the dark with a box and a red scarf around her neck. She pushes on, not really thinking but moving, feeling her body ebbing seaward. She stops at a slice of beach, rocks piled up, a concrete pier. She arrives at a sliver of what it used to be before McDonald’s rose upon the broken coast. She dances along the shore, tries to imagine it long once again. She pictures Icarus, Alexander’s island, whole, afloat on phosphorescent blue, haloed with snow white waves, a place before sons fell.

Amerika pulls her box to her chest and dances harder, the wind knitting lace with her hair. She twirls and dips and kicks up her heels, always the letter k at heart. Out of breath, she stops. She rests on the shore, feeling the sand, shattered crystal, embossing the backs of her thighs. The icy waves approach her toes but never dare to touch. Her right hand on the box at her side, she takes in as much air as her lungs will hold. She rests her eyes for a minute, it could only have been a minute. She thinks about icicles and trees bursting red in autumn, parades and clambakes. She thinks about Archie and making out on the beach. Then she thinks about falling, pale flesh, misty rose. She thinks about firebrick red, burnt sienna, and then plumes of dim gray.

When she opens her eyes she sees a shooting star zooming toward her. She smiles. Stars in my eyes. She blinks. It continues toward her. She blinks again. She thinks, Out of the blue. There are no sirens. A floating star heading toward the shore. In the twinkling of an eye. CNN will say: “Surface-to-Surface.” It will say: “Non-Existent Arc.” It will say: “Chinese Seersucker” and “Under the Radar.” It is missile number thirteen, the only one that makes contact. She thinks, Into thin air. Amerika picks up her box, kisses it, turns away from the moving star, and flings it as far away from herself as she can. She hears it explode on the pavement. She hears herself explode. Painting the town red.

When they come, they find the contents of Amerika’s box, charred, scattered, inexplicable. They find footprints of ballet flats, an invisible dance along the shoreline. They find the residue of loss, the triumph of fury. They find traces of a square peg in a round hole and the end of the future. Amerika’s box, Amerika, Radio City Rockette extraordinaire, never a mouse, never evil, into thin air she flies, like a kite.

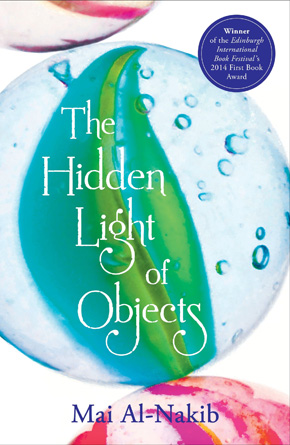

From the collection The Hidden Light of Objects.

Mai Al-Nakib was born in Kuwait, but lived in the US until the age of six. She holds a PhD in English literature from Brown University and teaches postcolonial studies and comparative literature at Kuwait University. The Hidden Light of Objects, her first collection of short stories, won the Edinburgh International Book Festival’s First Book Award in 2014, the first collection of short stories to ever win the award. She is currently writing her first novel. The Hidden Light of Objects is out now in paperback and eBook from Bloomsbury Qatar Foundation Publishing.

Mai Al-Nakib was born in Kuwait, but lived in the US until the age of six. She holds a PhD in English literature from Brown University and teaches postcolonial studies and comparative literature at Kuwait University. The Hidden Light of Objects, her first collection of short stories, won the Edinburgh International Book Festival’s First Book Award in 2014, the first collection of short stories to ever win the award. She is currently writing her first novel. The Hidden Light of Objects is out now in paperback and eBook from Bloomsbury Qatar Foundation Publishing.

Read more.

Author portrait © Omar Nakib