Avoid like the plague

by Sir Ernest GowersA cliché may be defined as a phrase whose aptness in a particular context when it was first invented has won it such popularity that it has become hackneyed, and is now used without thought in contexts where it is no longer apt. Clichés are notorious enemies of the precise word, and thus are by definition a bad thing, not to be employed by self-respecting writers. Judged by this test, some expressions are unquestionably and in all circumstances clichés. This is true in particular of verbose and facetious ways of saying simple things (conspicuous by its absence, tender mercies) and of phrases so threadbare that they cannot escape the suspicion of being used automatically (leave no stone unturned, acid test). But a vast number of other expressions may or may not be clichés. It depends on whether they are used unthinkingly as reach-me-downs, or have been deliberately chosen as the best means of saying what a writer wants to say.

What is a cliché is partly a matter of opinion. It is also a matter of occasion. Many may cease to be clichés if used carefully. Writers would be needlessly handicapped if they were never permitted such phrases as cross the Rubicon, thin end of the wedge and white elephant. These may be the fittest way of expressing what is meant. If you choose one of them for that reason you need not be afraid of being called a cliché-monger.

The trouble is that writers often use a cliché because they think it fine, or because it is the first thing that comes into their heads. It is always a danger signal when one word suggests another and Siamese twins are born – part and parcel, intents and purposes.1 There is no good reason why inconvenience should always be experienced by a person who suffers it and occasioned by the person who causes it. Single words too may become clichés, used so often that their edges become blunt while more exact words are neglected.

Those who resort carelessly to cliché are also given to overworking metaphors. Newly discovered metaphors shine like jewels. They enable a writer to convey briefly and vividly ideas that might otherwise need tedious exposition. What should we have done, in our present economic difficulties, without our targets, ceilings and bottlenecks? But the very seductiveness of metaphors makes them dangerous. New ones, in particular, tend to be used indiscriminately and soon get stale, but not before they have elbowed out words perhaps more commonplace but with meanings more precise. And almost all writers fall occasionally into the trap of using a metaphor infelicitously. It is worth taking great pains to avoid doing so, because the reader who notices it will deride you. The statesman who said that sections of the population were being “squeezed flat by inflation” was not then in his happiest vein, nor the enthusiastic scientist who announced the discovery of a “virgin field pregnant with possibilities”.2

1 In the decades since Gowers wrote disparagingly of the cliché to all intents and purposes, it has given rise to a corrupted version of itself, ‘ to all intensive purposes ’. This is no improvement on the original.

2 The Deputy Prime Minister not so long ago roundly declared, “We will not balance the books on the backs of the poor.”

From Plain Words: A Guide to the Use of English, published by Particular Books in hardback and eBook.

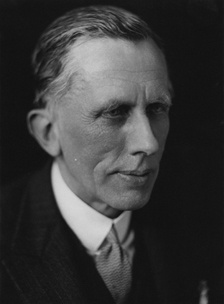

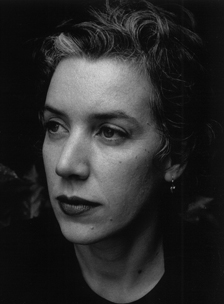

Sir Ernest Gowers was born in 1880, and became a leading civil servant, running the civil defence of London during the Second World War. He first wrote Plain Words as a guide to the proper use of English for the Civil Service. Within a year, its humour, charm and authority had made it a bestseller which has never since been out of print. Six decades on, writer Rebecca Gowers has created a new edition that both revises and celebrates her great-grandfather’s original. While the advice is updated to reflect altered English usage, Sir Ernest’s distinctive, witty voice is undimmed and his message remains vital: our writing should be as clear and comprehensible as possible, avoiding superfluous jargon and murky euphemisms. Read more.

Sir Ernest Gowers was born in 1880, and became a leading civil servant, running the civil defence of London during the Second World War. He first wrote Plain Words as a guide to the proper use of English for the Civil Service. Within a year, its humour, charm and authority had made it a bestseller which has never since been out of print. Six decades on, writer Rebecca Gowers has created a new edition that both revises and celebrates her great-grandfather’s original. While the advice is updated to reflect altered English usage, Sir Ernest’s distinctive, witty voice is undimmed and his message remains vital: our writing should be as clear and comprehensible as possible, avoiding superfluous jargon and murky euphemisms. Read more.