Behind the mask

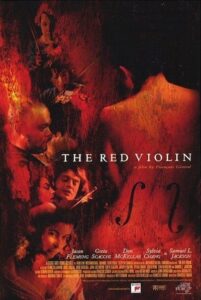

by Sarah LeipcigerThere’s a movie I love called The Red Violin, by Canadian filmmaker François Girard. I was in university when it came out in 1998, and watched it in one of those old theatres where the seats were upholstered in rough velour, the tickets were cheap and the popcorn stale. The Red Violin, if you’re not familiar, is a coming-of-age story with a notorious, almost mythical violin at its centre, so-called red because of the unique crimson tinge to its varnish. The story follows the instrument from its genesis (where we learn that the red in the violin’s varnish is actually the blood of the instrument maker’s wife, who dies in childbirth) to the present time over a period of three centuries, passing through the dexterous hands of various players all over the world: a child prodigy, an amorous virtuoso and a political rebel, to name a few. The life of the violin is reflected in the lives of those who possess it (and are possessed by it). The film is haunting and, though dated, though cheesy, still moves me.

But what really hooks me is the notion of this inanimate object being the centre of the piece: an artefact linking the stories of people who are separated by time and geography, people who remain unaware of their parts in the whole. A kind of alchemy occurs; the object comes to life. This is why, when I first heard about a certain death mask – an intriguing object with a mysterious, cross-cultural history – I became very excited.

Coming Up for Air is based on the true story of Norwegian manufacturer Asmund Laerdal and his connection to the death mask of L’Inconnue de la Seine, an unknown woman who (may or may not have) drowned herself in Paris’s Seine in 1890-something. I can’t tell you too much, it would ruin the story if I did, but I can tell you this: death masks (made from plaster casts taken from corpses in the first hours after death) were common in Europe during the Middle Ages through the 19th century. Initially created as resource material for sculptors and painters, earlier masks only depicted the faces of kings and military leaders and notable artists, guys like that, but eventually death masks became more commonplace, and were commissioned by regular folk simply to memorialise their dead.

I can also tell you that, whether you realise it or not, you are familiar with the face depicted by the death mask featured in Coming Up for Air. I cannot tell you how or why.

I am not the first person to have written about L’Inconnue de la Seine. While others have rendered her a victim, powerless, a muse to men, I have tried to give her a voice of power. A life in which she has agency, desires and a choice.”

It is true that Asmund Laerdal used the death mask of L’Inconnue de la Seine for one of his designs, and it is also true that his personal history contains a parallel that is too poetic, too dramatically perfect for the novelist to ignore (sorry, can’t tell you what this is either!). It is true that the identity of the unknown woman can never be learned. These truths were the spark for Coming Up for Air.

I am not the first person to have written about L’Inconnue de la Seine. She’s captured the imaginations of many, including Vladimir Nabakov and Anaïs Nin. I am just another hack – a lesser hack at that – in a long line of hacks who have taken ownership of this mysterious woman and created a fiction around her life. In my defence, while the others have rendered her a victim, powerless, a muse to men, I have tried to give her a voice of power. A life in which she has agency, desires and a choice.

So. I began with the true story of a manufacturer, a death mask and the mysterious woman behind the mask. But two strands felt, to be blatant, two-dimensional. I needed a third, but this wasn’t at first obvious. Sometimes you have to treat a story like a wary dog: approach too quickly and you’ll be bitten. Sometimes, you have to open your hand in supplication and let the story come to you.

So. I began with the true story of a manufacturer, a death mask and the mysterious woman behind the mask. But two strands felt, to be blatant, two-dimensional. I needed a third, but this wasn’t at first obvious. Sometimes you have to treat a story like a wary dog: approach too quickly and you’ll be bitten. Sometimes, you have to open your hand in supplication and let the story come to you.

The first several months of this project were spent in the British Library, learning about the work of Asmund Leardal, the physiology of drowning, death masks and Paris at the turn of the century. Wild water, breathing, the passing down of stories and the cycle of life began to emerge as common themes and from this my third strand began to take shape: Anouk, a young Canadian storyteller with cystic fibrosis (a disease which affects the lungs, the breath) and an affinity for swimming in open water. I now had three main characters, an artefact to bind them, and the beginnings of a fictional costume to somehow make fit onto a factual mannequin.

When you’re mixing fact and fiction you have an obligation towards transparency in how you balance fairness and accuracy with creative, dramatic needs. For example, I took great liberties with one aspect of Laerdal’s life (the poetic parallel which cannot be revealed here!), but had to come clean about the truth in the author’s note at the end of the book. I mean, it was a significantly large liberty. Also, cystic fibrosis is obviously a real condition that affects real people, so it was important to depict life with this condition in a way that was honest and respectful. To achieve this, I read a collection of memoirs, but also visited the homes of two very generous women: one who lives with CF herself and one whose daughter has the condition.

And as for L’Inconnue, as for Paris, well. We have to make sacrifices for our work and if a trip to Paris is required (and if you’re lucky enough to live thirty minutes from St Pancras station), so be it. I walked the streets in the rain for six days, loitered under bridges gazing into the river and seriously considered taking up smoking (it almost feels rude not to smoke in Paris). I hope this book does some justice to the woman whose face moulded the death mask at the centre of this story, but I cannot claim her voice is anything but invented: a projection, a means to a desired narrative, a fantasy.

Sarah Leipciger was born and raised in Canada and now lives in London with her three children and teaches creative writing to prisoners. Her short fiction has been shortlisted for the Asham Award, the Fish Prize and the Bridport Prize. Her first novel, the critically acclaimed The Mountain Can Wait, was published in 2015. Coming Up for Air, her second novel, is published in paperback, eBook and audio download by Black Swan/Transworld Digital.

Sarah Leipciger was born and raised in Canada and now lives in London with her three children and teaches creative writing to prisoners. Her short fiction has been shortlisted for the Asham Award, the Fish Prize and the Bridport Prize. Her first novel, the critically acclaimed The Mountain Can Wait, was published in 2015. Coming Up for Air, her second novel, is published in paperback, eBook and audio download by Black Swan/Transworld Digital.

Read more

@SarahLeipciger

@DoubledayUK