Boy wanderer

by Sam Garrett

“A masterwork of comic pathos… one of the finest studies of youthful malaise ever written.” Eileen Battersby, Irish Times

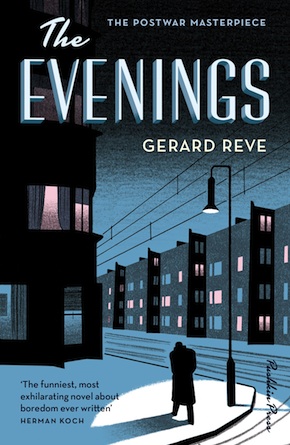

One of the most intense pleasures that can overcome any translator is the joy you feel when you take a book you’ve been hungering after for decades and run it through the mill of your imagination. That was my good fortune with The Evenings by Gerard Reve. Written back in 1947 and first published in English almost 70 years later, its ‘hero’, Frits van Egters, belongs to that fraternity of fictional characters who get under your skin and never, ever let you go.

According to my notes, I first read the novel in the autumn of 1983. That means I was only twenty-seven, my eldest son was one year old, my mother was still alive. I still had vivid memories of what it meant to groan beneath the parental yoke, and I was still very much a stranger walking the streets of Amsterdam. In wintertime the market near our home seemed to deal almost exclusively in several varieties of cabbage (a vegetable which, in its various olfactory manifestations, figures as leitmotif in The Evenings), and in carrots the size of a baby’s forearm, all wrapped in rather suspect-looking newsprint. With its vacant storefronts and trashed houses, the area between De Wittenkade and Van Hallstraat, where Gerard Kornelis van het Reve was born in 1923, looked – for a variety of reasons – as though the Wehrmacht had marched out only five minutes earlier. On Sundays and public holidays, most neighbourhoods outside the ring of canals had all the liveliness of a public cemetery in the rain. Amsterdam was still under the spell of the post-war doldrums that The Evenings depicts to a tee.

In 1983 I was still a relative novice in the Dutch language, but upon first reading this quirky Christmas chronicle I was not only bowled over by its baleful humour and underlying darkness, but I was also impressed by Frits. His bold cynicism, his socially inappropriate jokes, his desperate nightly forays to the homes of friends and his highly ambivalent relationship with both those friends and his own parents, it all rang a bell with the young man in me. The desire to allow others, my American friends in particular, to read this peculiar, subversive book – and to somehow also get to know me better – slumbered in me for a very long time.

What struck me now, in my early sixties, was that Frits van Egters is above all a boy. A very funny boy, at times an extremely insightful boy and a nasty one too, but a boy nonetheless.”

Some 35 years later, reviewers in the UK and the US spoke of The Evenings as a ‘lost’ masterpiece, a “cornerstone manqué of European literature”. But the novel was only ‘lost’, of course, in the sense that it had never been translated into English, not until Pushkin Press gave me the opportunity to do so in 2016. At any moment between its original publication in 1947 and 2016, some 15 million Dutch speakers would have had no problem getting their hands on the latest edition of this perennially disturbing novel, this post-adolescent Journey to the End of the Night with former high-school teachers, parents, petty thieves and colleagues in the place of barmy French officers and bourgeois émigrés to darkest Africa. De avonden was a staple of Dutch required reading lists.

Every Dutch person who reads, in other words, knew and knows Frits van Egters. I thought. Yet almost forty years after my first reading I realised it was a different Frits in whose company I – as his translator, and in some strange way also as his guardian – finally made that deceptively becalmed journey through ten chapters and just as many days of his life. What had changed?

What triggered that realisation, I think, was a comment someone made soon after I was commissioned to do the translation. It was at a book launch in the newly renovated, uber-hip gas factory at the western edge of Amsterdam, a venue in total sync with the changes the town has gone through since I arrived. The man, a Dutch publisher, told me that he had recently re-read Reve’s novelistic debut and found himself wondering whether any young person today could conceivably relate to the book.

I was shocked, and not a little dismayed. Had I been mistaken, somehow, in my appraisal of the novel’s worth? I went back and read. And what struck me now, in my early sixties, was that Frits van Egters is above all a boy. A very funny boy, at times an extremely insightful boy and a nasty one too, but a boy nonetheless. Not someone I looked up to, but also not someone I looked down on. More like someone I had been like, or at least someone I could try to understand. As I read on, I also noticed that the passing of the years had made the book even more poignant. Youth, in all its panicky over-examination, can be a hell, my friends. And if ever anyone has been stretched on the rack of thinking too much, it is Frits van Egters.

Holding the first hardback edition of The Evenings in my hands was not entirely unlike being present at a birth.”

In the months that followed, as I buckled down to the actual work of translation, this made me see Reve’s protagonist in a different light. All the delights I had been anticipating – the lush and disturbing dream sequences, the weirdly skewed dialogues and, unforgettably, Frits’s own overwrought interior monologues were there, untouched, like virgin forest for me to blaze a trail through. (“After having examined his head from every angle once more, he combed his hair and turned the light back on. ‘Let us assess the effect created by daylight in combination with an incandescent lamp,’ he said to himself. ‘Very like a giant turnip,’ he said out loud then, ‘yet with telltale signs of sagacity.’”) But there was another dimension as well. Not pity, not awe, but a kind of solicitousness, as though at the re-emergence of Frits van Egters, with all his foibles and in his all his brilliance, I was to be the midwife.

In the end, holding the first hardback edition of The Evenings in my hands was not entirely unlike being present at a birth. In English too now, Frits wailed and breathed and no longer existed solely as a sort of ultrasound image in my imagination. Now he no longer needed me in order to work his peculiar spell, annoying and amusing, horrifying and delighting new readers in an entirely new voice, but one that is also entirely his own.

Sam Garrett (right) is a translator of novels and non-fiction, who divides his time between Amsterdam and the French Pyrenees. He won the British Society of Authors’ Vondel Prize for Dutch-English translation in 2003 and 2009. In 2012, his translation of The Dinner by Herman Koch spent two months on the New York Times bestseller list and became the most popular Dutch novel ever translated into English. His other works have been shortlisted for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award (2005 and 2013), the Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Award (2010), the PEN Translation Prize (2014) and the Best Translated Book Award (2014).

Sam Garrett (right) is a translator of novels and non-fiction, who divides his time between Amsterdam and the French Pyrenees. He won the British Society of Authors’ Vondel Prize for Dutch-English translation in 2003 and 2009. In 2012, his translation of The Dinner by Herman Koch spent two months on the New York Times bestseller list and became the most popular Dutch novel ever translated into English. His other works have been shortlisted for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award (2005 and 2013), the Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Award (2010), the PEN Translation Prize (2014) and the Best Translated Book Award (2014).

Gerard Reve (1923–2006) is considered one of the greatest post-war Dutch authors, and was also the first openly gay writer in the country’s history. A complicated and controversial character, his 1947 debut The Evenings was chosen as one of the nation’s 10 favourite books by the readers of a leading Dutch newspaper while the Society of Dutch Literature ranked it as the Netherlands’ best novel of all time. Sam Garrett’s translation of The Evenings is out now in paperback from Pushkin Press.

Read more