Camilla Bruce: Away with the faeries

by Mark ReynoldsCamilla Bruce’s debut novel You Let Me In is a gripping, genre-shifting psychological thriller written in the form of a long letter-cum-memoir from missing, 74-year-old romance novelist Cassandra Tipp to nephew and niece Janus and Penelope – her only living heirs. In the letter, she tells dark parallel tales about a childhood spent in the woods among faery spirits, and a husband known as Pepper-Man made of twigs, leaves, bones and feathers; and of a cruelly treated girl growing up in the shadows, who may be responsible for the murders of three people closest to her. She also reveals that her worldly goods are to be bequeathed with troubling baggage…

MR: Folk tales and faery stories exist to help anticipate and make sense of life’s pitfalls and dangers. In what ways are they also used to deflect from the realities of anticipated or past trauma?

CB: I have always thought that these tales gives us a language to talk about things that are otherwise hard to approach. It is a common theory, at least in Norway, that most stories about supposedly real faerie abductions are actually about sexual assault, but with all the shame and taboos surrounding the subject in the past, the victims found it easier to ‘blame the faeries’ for damage done and time unaccounted for. Disguising hurt in that way gave the victims a way of talking about their trauma without placing blame or facing judgement.

There is also that thing where, if you repeat a story enough times, it becomes the truth, even to yourself, and I definitely think that can happen, in the past but also now, as a way of protecting yourself from harm; much like a psychological Band-Aid that protects the wound while it attempts to heal.

Can Cassie’s career as a romance novelist be seen in a similarly escapist light?

Absolutely – I think all creative pursuits can be effective in that way. I have often used writing as a coping strategy, especially when I was younger, and Cassie, being my brainchild, inherited that trait.

Which folk and faery stories particularly influenced you when you were a child, and which have resonated into your adult life?

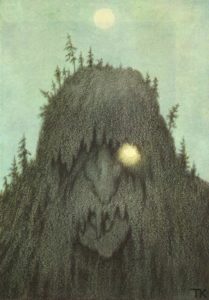

I grew up on a mixture of Grimm’s and Norwegian fairy tales, and loved both traditions equally, though the folk aspect is much stronger in the Norwegian ones, where the trolls abound. I do not remember how I was first introduced to the more faerie-centric stories, but I have been drawn to the idea of nature spirits and hidden creatures for as long as I can remember. As a child, I was particularly fond of the nøkk, which is a Scandinavian kelpie of sorts, only he is just as often a man as a horse, and can teach you to play the fiddle for a price.

I do not think I have shed any of those stories, to be honest. They continue to influence me even now. I am taken with the faeries’ elusiveness; how they shift and change – and their societies as well, how they are like twisted mirror versions of our own, reflecting it back in uncanny ways. I think all folklore is excellent clay for stories that feels relevant even for people today.

The setting and time period in You Let Me In is broadly contemporary but deliberately ambiguous. Your potted biography points out that you, like Cassie, grew up next to an Iron Age burial mound. Were there local stories about the rites, rituals or supernatural occurrences rumoured to have taken place there?

I grew up in an old forest studded with Iron Age burial mounds, so the one closest to our house was only one of many. I do not think anyone but me thought of them as particularly mysterious, though. Most of them had been robbed at some point and had deep hollows in the middle, which made them excellent houses or forts, and we played in them quite often, not really considering that they were – in fact – graves.

The forest has since become a golf course, and at least some of the mounds now have proper signs and protection, but back then they were something that was just there, and I do not think I ever heard any rumours about mysterious happenings or rites – I made all of that up myself.

Historically, the term ‘faerie’ has been used to describe all sorts of things: ghosts, demons and witches’ familiars. I wanted the text to reflect that multitude of possibilities.”

Is Cassie’s vampiric Pepper-Man, and the faery community of dead humans looking to inhabit new life forms, based on any single tradition, or does it draw from a variety of sources?

The faeries in You Let Me In are definitely a result of accumulated knowledge and not inspired by one tradition in particular. I deliberately refrained from doing any research to let them take shape from what was already in my head. I think there are a lot of old stories in there – cautionary tales – but also a drizzle of modern Young Adult, and perhaps even some New Age-inspired lore.

Historically, the term ‘faerie’ has been used to describe all sorts of things: ghosts, demons and witches’ familiars, and it is hard to pinpoint exactly what they are. I wanted the text to reflect that multitude of possibilities.

In what ways do the faeries of Norway and Scandinavia differ from other traditions?

The Scandinavian faeries would be the hulder people, which is an assembly of mostly human-sized creatures closely related to trolls (the line between the two species is blurry). There is also a smaller sub-species called vetter. The most famous hulder is Huldra, who is a beautiful woman with a cow’s tail.

There is some overlap between Scandinavian and Celtic traditions, but where the Celtic faerie society resembles a medieval court of sorts, the hulder society mirrors the Scandinavian farming society of yore. The Norwegian hulder people are mostly found in the mountains, where they keep vast farms and herds of black cows underground, or inside the mountain itself. Most of their interactions with humans happen in connection with summer farming in mountain pastures.

Though the hulder people engage in many traditional faerie activities such as baby-swapping and abductions, it is my impression is that they are more often erotic in nature than their counterparts in other places, and they frequently aim to marry humans. Like faeries everywhere, they are connected to death and the underworld, and burial mounds were often referred to as ‘hulder mounds’.

At what point did the novel take the form of a letter from Cassie to her nephew and niece, and how did this structure let you in?

I wish I could pinpoint the exact moment I came up with the letter, but that is sadly lost in the fog. I know I had one false start before the letter manifested, but once it did, the voice came with it, and I wrote the first draft over six intensive weeks.

This hulder‘s disguise as a farm girl is undermined by the tail peeking from her skirt. From Svenska folksägner by Herman Hofberg, 1882. Wikimedia Commons

Some of the juxtapositions of the fantastical and the everyday are darkly hilarious. Dr Martin’s book about Cassie’s case, which led to her acquittal for murder, is called Away with the Fairies: A Study in Trauma-Induced Psychosis, and the dialogue between the pair is littered with non sequiturs and misunderstandings. How important is humour as a release from horror or trauma – for the reader, as much as for victims?

I think humour is what makes the bad bearable, both for readers and for victims. The scenes with Dr Martin were specifically inspired by my own and others’ encounters with mental health professionals and other people designated to help in times of crisis. No matter how well-meaning the doctor is, he lacks the necessary experience to understand where Cassie is coming from – the dialogue can never be truly constructive because there is a crucial piece of understanding missing. This is no one’s fault, it is what it is, but these types of situations make for excellent humour if you are willing and able to see it.

Did you have an imaginary friend or friends when you were growing up?

I did – and that is actually an eerie story. I do not remember much about my invisible friend, Sisi, myself, other than she had brown hair and was convenient to blame if I had not done my chores, but my mother recalled her vividly. She told me that one day when I was about four, while we were staying in a family cabin up in the mountains, I made a ring of pebbles on the ground by a brook and said, “Sisi is dead now,” and then I never spoke of her again. I can vaguely recall the sight of the pebbles, but nothing more than that.

I remember eavesdropping on adults who discussed the paranormal in hushed voices. That, of course, made me extremely curious, and I started seeking out books on the supernatural.”

At what age were you first drawn to supernatural, Gothic or speculative fiction, and which books or authors particularly inspired you to write?

I grew up in a time and place where it was not that uncommon to believe in ghosts and other things that go bump in the night, and I remember eavesdropping on adults who discussed the paranormal in hushed voices. That, of course, made me extremely curious, and I started seeking out books on the supernatural, both fiction and non-fiction, at a very tender age. My favourites at eleven were Dracula and The Burning Court, and I was already writing my own stories by then. I remember my teacher once urged me to write about “a sunny day at grandma’s house”, because the dark themes in my stories unnerved her.

We also had this really long book series going in Scandinavia in the eighties, about a cursed family where an evil child with magical powers was born into every generation. The series, The Legend of the Ice People by Margit Sandemo, introduced a whole generation of young women to the allures of witchcraft and demonic sex. Looking back, I realise it was an early Scandinavian attempt at supernatural romance, but at the time it was brilliantly unique, and the series was hugely popular. It also drew on Scandinavian folklore and I learned a lot I did not know from reading those books – which I did for the first time at age twelve. I would absolutely be lying if I said those novels were not a huge inspiration that influenced my early writing.

Your next book, In the Garden of Spite, is a historical novel based on the life of the Norwegian-American serial killer Belle Gunness. What attracted you to her story; and in what ways does it echo Cassie’s?

Belle Gunness came from the same part of Norway as I do, so that was obviously a big part of the initial attraction. Her life as a struggling and oftentimes single mother was also uncomfortably relatable to me. I just could not fathom how a dirt-poor girl from rural Norway ended up in Indiana with a yard full of corpses – and perhaps even got away with it all.

Once I started to look into the story, it turned out that what I already knew was just a fraction of the tapestry, and I found a surprising number of themes that I felt would resonate with people today. Writing a folkloric monster back to flesh and blood after a hundred-plus years has been an immensely satisfying undertaking – though not for the faint of heart.

Belle and Cassie are similar in their failure to fit in, they are both struggling to maintain an appearance of normality, and they are both, each in their way, fighting for survival, which are all themes that attract me.

What are you writing next?

I am working on a new speculative novel, and a new historical one. Both projects are very new and tender, however, so I cannot say much more this point.

Camilla Bruce was born central Norway. She has a master’s degree in comparative literature and has co-run a small press that published dark fairy tales. She currently lives in Trondheim with her son and cat. You Let Me In was published in hardback by Bantam Press and is now available in paperback, eBook and audio download from Black Swan/Transworld Digital.

Camilla Bruce was born central Norway. She has a master’s degree in comparative literature and has co-run a small press that published dark fairy tales. She currently lives in Trondheim with her son and cat. You Let Me In was published in hardback by Bantam Press and is now available in paperback, eBook and audio download from Black Swan/Transworld Digital.

Read more

camillabruce.com

@millacream

Author portrait © Lene J. Løkkhaug

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

wearebookanista