A chance to tell his story

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“Probably the best version of The Aeneid in modern English.” Jim O’Hara, University of North Carolina

A boy grows in rural northern Italy, in the midst of pastoral peace and bloody internecine war; little is known about his parents or his childhood, for all the many stories that would be told about him once he became a novus homo, poet, imperial confidant, the voice of a people and an empire – once he was proclaimed a theios aner or god-like man, a magician and a divine oracle. His own elusive, yet suggestive term for himself would be vates – a speaker of prophecy, or clairvoyant poet. Yet one sees the multiple snippets of experience, the rich hues of faded or vivid memories, and hears the echoes of haunting or arousing voices that defined him throughout his poetry, which would not only indelibly mark Western imagination and beyond, but would crucially determine the prism through which many of our ethical, civic or historical choices would be made – on a personal level, as well as on the level of nations or continents. Virgil’s poems are not simply part of a literary heritage; one could argue that together they are the compendia of a new language for history and human experience. They are unprecedented, bold and audacious foundational and aetiological narratives not only for Rome and its new emperor, but for the course of what they unequivocally claim to be a redefined private and public human existence.

The Romans had a particular predilection for self-legitimising stories that established their place and reason of being. Unlike the more broadly epistemological, cosmological narratives of the Greeks, with their moral tales and origin stories of people, cities, gods and heroes, their dramas of human virtue or folly, or the psychological tales of humanisation told elsewhere, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh, the Mahabharata, or the Ramayana, Roman stories of becoming and being do not simply focus on genealogies, natural causes and historical beginnings, or on parables of political or individual characterology. Their primary angst was for an ordained purpose and destiny, for a claim not simply over the past, but especially over futurity. They combine the atavism of superstition (as evinced in divination, auspicious or inauspicious days, conveniently ‘lost’ Sibylline prescriptions ruling over the uncertainty of human temporality, the veneration of the vagaries of fortune and fate), with a polemicised rhetoric of primacy, validation and adversarial self-definition. They profess an unshakeable claim to cultural continuity through amalgamation and change, an aetiology of the right to ‘other’ others and to assimilate, erase, appropriate, dominate.

The Aeneid grew out of a long process of reflection by means of which Virgil would hone and refine his understanding of the purpose of literature, of words and stories, his vision of worlds, and the role and value of individual lives.”

We rarely question the eerily normalised bow slur between a Greek and a Roman paradigm, often speaking of the Greek and Roman world. And yet an exploration of the inherent tensions and radical paradoxes in any undiversified conceptualisation of the classical world can yield staggeringly subversive new readings of our ‘universal’ history, certainly a more lucid, critical, vitally needed understanding of our ‘Western’ paradigm. Few texts offer themselves to such a fundamental reassessment of who we are, who we came to be, more vocally than Virgil’s Aeneid: it is a formidable repository of cultural markers and historical evidence, a stark record of deliberate actions of transition, translation, even traducement. The Romans felt a profound, even fierce discomfort and ambiguity as regards the mongrel Hellenism that ‘tainted’ their Roman identity, and this double bind of attraction and resentment, of true self and compromised imitation, is a key concern of Virgil’s poem. Its own history of inception, gestation and reception is an extraordinary demonstration of all that was and is at stake. It grew out of a long process of reflection on Virgil’s part, by means of which he would hone and refine his understanding of the purpose of literature, of words and stories, his vision of worlds, and the role and value of individual lives.

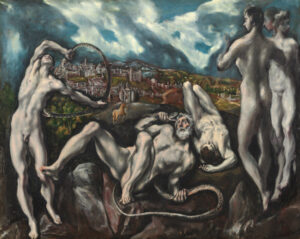

Laocoön by El Greco, c. 1610–1614. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Already from the Eclogues and the Georgics Virgil makes a firm statement that his project is not simply original creation, or a simple story with a distinct focus, an Aristotelian beginning, middle and end. He aims instead for a supremely dynamic narrative of cultural and historical hybridisation: old and new, rural and urban, Greek and Roman, vernacular (volk) and high cultural, indigenous and ‘other’, variations on a theme and original models, peace and war, civic and military, human and divine. They all morph and interlace in carefully arranged landscapes of new ideas, new sociohistorical structures, new truths and new memories. Virgil has an invariably public, almost messianic perception of himself as a narrative agent or subtly embedded persona and voice, and this cannot be contested, whether or not one sees irony in his words, one or many voices, layers of fiction, meta-textualities. He is not a, but the poet, the mouthpiece of the muses, with a self-conscious duty to rise to the occasion: “surgamus”, “let us rise”, as he tells himself before embarking on the Aeneid.

Themes that are but nuanced narrative tropes in the earlier two poems come fully into their own in this new work, hailed by Propertius as “something greater than the Iliad”, the truly maior opus of the Virgilian corpus. Virgil has solidly presumed throughout his work (in fact depends upon) an audience that will confidently and unerringly pick on and recognise the metatextual references, the mythographical and mythological associations, the gestures of defamiliarisation, domestication, acculturation, evocation, embedment and revision. His readers are deemed to be masters of the intricate verbal and allusory patterns he constructs so effortlessly and thrillingly, an experience the lay modern reader is perhaps not as likely to share. They would have known to recognise aliases, metaphors, allegories or historical innuendos, however subtle or carefully concealed, and they would have noted modulations and readaptations of themes and familiar tales, textual cross-dressings and travesties, the incursion of echoes, shadows, spaces.

To read the Aeneid with a keen eye for its historical details is to engage with Virgil on a subject of the utmost urgency: what values, cultural paradigms, civilising gestures should define our world?

On one level, it was all part of a great game of hide-and-seek, a masque of the highest order, an interactive pageant as favoured by the Romans of Virgil’s time. On another, it was a masterstroke of translation at its most fundamental etymological level, as Philip Hardie has pointed out: that of shifting the place of primary focus, what would become known as the process of translatio imperium, the transference of power, cultural agency, or even the right to political or ordinary existence, from past ruler to new, from older civilising category to new dominant order. In the Aeneid Virgil creates an epic of Rome (not just an epic for Augustus) that is at every level such a translatio of the epopoeias of the cultures that had not only pre-existed it, but were still vital, living traditions: both Greece and Egypt are present throughout, as well as Carthage and Persia. Each time the matrix of history is flipped, the order reversed, the paradigms converted. Most famously of all, Homer’s stories of war and peace are turned back-to-front, their human essence replaced by broad, billboard-like brushstrokes. The Iliadic ethology exposed the ravages and alienation, the dehumanisation inflicted by war, the pain and loss on either side. Its greatest bully is a Greek, Agamemnon; its most heart-rending scenes include the parting of a Trojan, Hector, from his wife and child, and the devastation of a Trojan father and king, Priam, at the horrific fate of his son. The Odyssey is not just a tale of Sindbad-like adventures, of monsters, villains, ogres and supernatural dangers. It is above all a process of rehumanisation, a redeeming of individual lives and of public life, culminating in the rejection of violence and retributive justice. Virgil tilts and twists Homer’s proposed example of the life worth living, swaps the Platonic model of Odysseus for a very different human type, nullifies the debates on anger, revenge, brutality that form the basis of both Homeric epics as well as the Oresteia, subverts explicitly the cultural and civilising programme of Pericles’ funerary speech in favour of new principles of necessity and Romanitas – and global rulership. To read the Aeneid with a keen eye for its historical details, its ideological suggestions, its mythological patterns, its organic referentiality, is to engage with Virgil on a subject of the utmost urgency: what values, cultural paradigms, civilising gestures should define our world?

Like Homer, Virgil sees himself not only as the transcriber of a tradition – of multiple traditions – but as the critical agent of interpretation of those traditions: he selects what elements of literature, philosophy, history he wishes to endorse, preserve or invalidate. Virgil’s story of Aeneas and of Rome is his own version of a truth that he felt needed to be told, a response he saw as vital, to counter past and present alternative accounts. Horace in the Satires and in the Epodes would take him to task for his gloss over the political realities of the time, as would Ovid and, later, Lucan, in his uniquely un-Roman Civil War. Dante would read him very differently, setting the tone for a new dialectics on the classics of his time, and of ours: which paradigm to choose? And how? And what makes us the choosers of paradigms at all?

These are questions that are at the heart of Shadi Bartsch’s new translation of the Aeneid, which comes with a lengthy, pugnacious and rather exhilarating introduction, and an unabashedly philological and characterful declaration of intent as regards her decision to offer readers yet another English variant of Virgil’s poem. Bartsch is keenly alert to the inflections of language, the weight and impact of sounds, the hermeneutical muscle memory of repetition, figures of speech, stylistics and lexical modalities, and the way in which the use of a polysemous term can determine or bias understanding (her examples are the verb condo, which can mean to found a city or plunge a sword, and the standard tag-term for Aeneas, pius). She believes in what she calls “a conscious philosophy of translation”, as well as in a personal voice: “for all my efforts to be transparent, this is my Aeneid.” Her translation is not only intended to add to the existing corpus a new text that will enhance the clarity of the original and engage modern readers with a very old poem; it is specifically envisioned as a bold gesture of reaffirmation as regards the value of the classics, their critical necessity in our culture today, in our intellectual community, especially in our human and sociohistorical analysis and understanding of ourselves.

For Bartsch, the elusiveness of a single truth or meaning is what makes the poem an invaluable prism not only into the past, but also and crucially into the present.”

The Aeneid for Bartsch exemplifies the complexity of the European tradition, the multiple perspectives of Western consciousness, the inherent process of questioning and self-scrutiny that it entails and is based on. If anything, the Aeneid has been ‘a text for all seasons’ and a ‘servant of many masters’: it has been read, misread, reappraised, it has even been ‘completed’: in the 15th century, Maphaeus Vegius would add a thirteenth book to Virgil’s twelve, to placate those who had found the original ending of the epic a little too unsettling or perplexing. For Bartsch, the elusiveness of a single truth or meaning is what makes the poem an invaluable prism not only into the past, but also and crucially into the present. “Through the ages [the Aeneid] has served as an illuminating work to think with that reveals as much about those who encounter its complex story. [It has] much to tell us about the values that those generations brought with them to the encounter.” There have been several dominant strains of interpretation as far as the Aeneid is concerned, and Bartsch aligns herself with those who see in the poem what David Quint has called “the hermeneutics of suspicion”: rather than a celebration of Augustus and his rule, “we modern readers often feel the epic invites us to reflect on the negative cost of empire, the way history belongs to the victors, and the discredited voices that fall out of memory.” It is an argument that has perhaps found its most evocative proponents in Michael C.J. Putnam and S.J. Harrison, its reflective analysts in Charles Martindale, Philip Hardie, Denis Feeney or Alessandro Schiesaro, its staunch resisters in Ronald Syme or Paul Zanker, Richard A. Bauman. For Bartsch herself, the Aeneid is especially “an account of how a refugee from Asia… led his followers west to establish a new empire in Italy.”

Few refugees come with shiploads of armed forces, however, and royal recommendations to aid them in their cause, no matter the magnitude of loss they left behind, and some modern readers may find Bartsch’s liberal application of current socio-political categories something to think with, yet this is precisely what the Aeneid is all about: it cannot be read tamely, it refuses passivity or noncommittal engagement, it will baulk at any attempt to simplify or sanitise it. Perhaps Alexander Pope did not get it quite right when he wrote that “Homer makes us hearers and Virgil leaves us readers.” Or did he? There is a mesmeric quality to Virgil that enthrals us into entering the poem’s fiction totally, in reading the story from the inside, as it unfolds. Its contradictoriness is part of the experience, as well as being part of Virgil’s understanding of a new human – Roman – ethics, where a realpolitik of required individual and political action and tragic consequences go hand in hand in an irredeemable pattern of not simply inevitability, but necessity.

Bartsch goes to great lengths to theorise on the Aeneid as a poem that “is in many ways a story about stories (or national myths) and how they work”, exposing “the mechanisms at work in wholesome origin-stories and justifications of imperial aggression”, as well as being a work always conscious of “its stains as fiction”, an exercise of restoring to memory what has been damned to oblivion. She offers close readings of word patterns and careful character analysis, especially of the literary precedents to Aeneas. As she says, “in my translation I have made a conscious effort not to automatically accept the poem’s dominant perspectives.” Yet perhaps this conscious effort has also created its own unconscious bias of interpretation? By externalising the poem and Virgil from their context and time, especially from the quality of the poem’s engagement with what Virgil clearly sees as his counter-voices (and “the discredited voices that fall out of memory”), Bartsch shies away from many of the harsh structural realities of Virgil’s own (literary) truth: from his gender politics, to his cultural polemics, to the poem’s selective memory and praxis of memorialisation, or even its complex authorial intentions and historical responsiveness. It can also be argued strongly that when the poem does purport to contain hypothetical critical perspectives towards its own subject, it does so only for the purpose of destabilising the premises of a clear ethical judgement, and of moral responsibility on the part of the readers: it creates the position of sanctioned historical onlookers, for whom historical agency or engagement is simply beyond their control, or for whom certain courses of action are a tragic necessity. Bartsch acknowledges that the question is not an easy one: “As Roland Barthes has noted, what we must guard against is not so much ideology, as the way in which ideology masks and conceals itself”, even if her own conclusion (perhaps not necessarily convincing) is that “Vergil’s Aeneid refuses to mask itself.”

For readers who come to the poem for the very first time, Bartsch’s translation will mark them and stay with them perhaps for life.”

What of the translation itself? Almost every translator of Virgil’s work has had to grapple with the question of how to bring both poet and words over to the reader. Should they create a new vernacular close to the target language, audience and contemporaneous experience? Should they opt for a more ‘period’ rendition which allows for historical authenticity? How about stylistics, rhyme schemes, the sound itself of language, the connotations of words, states of being, experiences, that may have changed across the ages? In a seminal critical survey of the Aeneid’s translation history, Susanna Morton Braund discusses what she calls the “foreignising” or “domestication” of the text to explore not only its appropriating gestures, or its own fate of being appropriated, but especially the more dynamic process of creating, through the acknowledgement of the mediation of language, history, culture and individual experience, a prism of reflection through which to look at the Aeneid both in order to study its meaning(s) and intention(s), but also so as to examine our own critical perspectives, projections, spots or vast areas of willed or unwitting blindness. The pendulum of proximity or distancing has swung far and wide, from Virgil’s own ‘translation’ (or rewriting) of the texts, Greek or Latin, that he embeds or echoes in his works, to Dryden’s claim to have made Virgil speak the English (and therefore the experience) of his own age,to the vocal ‘Latinophobia’ of the Russians until the forced rehabilitation of the classics imposed by Peter the Great, and the revival of interest in Russian Aeneids, which uncannily coincides with Tolstoy’s War & Peace. The question of language and betrayal, and the critical place of the Aeneid, its tradition and its translations, are superbly captured in Michel Foucault’s Les mots qui saignent, and Morton Braund shows, with thrilling attention to grand schemes and details, how decisions on metre or tonality, on rhyme or the precise correspondence of words and meanings, on the re-orchestration of voices and their timbre, can transform the value itself of the readerly relationship and experience, Virgil’s truth and how we see it.

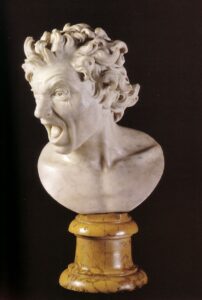

Damned Soul (perhaps Turnus’ soul fleeing to Hades) by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, c. 1619. Palazzo di Spagna, Rome

Bartsch has followed a similar translating practice, claiming to “have tried to create a radically different reading experience by being attentive to the pace of Virgil’s epic. Latin, a dense, lapidate language… can say much in a few words” – an unacknowledged echo of Morton Braund’s description of “Vergil’s laconic, almost lapidary style”. ‘Her’ Aeneid, as she has called her translation, is eminently readable, absorbing, almost life-like in its fluidity, vibrancy and resonance. For readers who come to the poem for the very first time, it will mark them and stay with them perhaps for life. Yet anyone who picks up the Bartsch translation with a knowledge of Virgil’s Latin, or even after having read any of the older versions, or perhaps the relatively recent translations of Stanley Lombardo, Robert Fagles and Frederick Ahl, will feel a sense of double vision. From the very first line, the unforgettable “arma virumque cano”, with its stark emphasis on the dual inexorability of war and human mortality, is lulled away as “My story is of war and a man”, the loss of the dithyrambic cano, ‘I sing’ (perhaps even ‘I wail’ or ‘I proclaim’), raising immediate questions. Vocabulary choices throughout flex Virgil’s verses and his meaning towards Bartsch’s own perceptions of the poem, often in a way that disallows a more critical (objective) encounter with the poem. Overall, the tone is too conversational, more fireside story than grand narrative (and the Aeneid is, if anything, a master narrative of a certain magnitude and greatness). To many, this will seem perhaps to be to the poem’s loss, rather than a gain in a broader readership, to which this edition clearly aims, with an impressive set of explanatory notes and a rich glossary of names.

Yet perhaps none of this matters as much as the fact that we have once again gone back in order to look ahead. That we have sought to engage with those who have thought before us about questions that remain still critically and tragically unresolved. That we have deemed their voices, whether infuriating or wise, disturbing, controversial or revelatory, as part of our story and our conversation, as truths or false counsellors that we cannot ignore, or simply purge from our lives and minds. Whatever our attitude towards Virgil and Rome, Augustus and his Imperium, the Aeneid remains a formidable testimony on our engagement with our own humanity and history, our efforts to create a social existence, to define mortal being, to trace frames of reference and to lay claims on knowability, answerability, individual and public destiny, the I and Thou. It is a critically revealing story and history, an inalienably meaningful document of who we are, have wished to be, can perhaps decide to be.

Shadi Bartsch-Zimmer is the Helen A. Regenstein Professor at the University of Chicago. She works on Roman imperial literature, the history of rhetoric and philosophy, and the reception of the Western classical tradition in contemporary China. She has been a Guggenheim fellow, edits the journal KNOW, and has held visiting scholar positions at the University of St Andrews, in Taipei and in Rome. The Aeneid: A New Translation is published in hardback and eBook by Profile Books.

Shadi Bartsch-Zimmer is the Helen A. Regenstein Professor at the University of Chicago. She works on Roman imperial literature, the history of rhetoric and philosophy, and the reception of the Western classical tradition in contemporary China. She has been a Guggenheim fellow, edits the journal KNOW, and has held visiting scholar positions at the University of St Andrews, in Taipei and in Rome. The Aeneid: A New Translation is published in hardback and eBook by Profile Books.

Read more

shadibartsch.com

@ShadiBartsch

@ProfileBooks

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

bookanista.com/author/mika/