Christopher Bollen: Distraction games

by Lucy Scholes

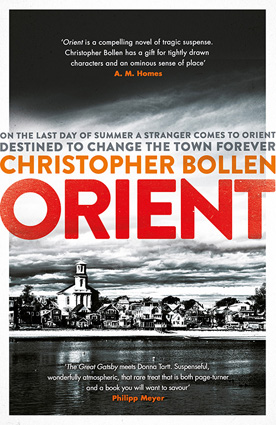

“A compelling novel of tragic suspense.” A.M. Homes

Christopher Bollen’s second novel Orient takes its title from the name of the small hamlet on the tip of the North Fork of Long Island. His story begins as summer draws to a close. Mills Chevern, a 19-year-old foster-home kid-turned-drifter who hails from California is taken pity on by Orient native Paul Benchley, a middle-aged architect living in Manhattan who finds the young man passed out in the hallway of his Chinatown apartment building. Paul’s about to head home to Orient, he’s inherited his mother’s old house after she died the previous year and the junk that’s accumulated needs clearing out. He offers Mills bed, board, and more importantly a chance to get away from the temptations of the city in return for help around the house. It all seems too good to be true, but soon after their arrival a series of tragedies rock the small community – the body of a local handyman is found floating in the bay; an old woman dies in mysterious circumstances; and then there’s a devastating house fire. The townsfolk close ranks and Mills finds himself under suspicion.

Like many of the best small-town-set mysteries, Orient is as much about the community as the unravelling of the mystery; the two elements are inextricably entwined. It’s the classic Twin Peaks formula, albeit without Lynch’s offbeat crazy. But Bollen’s setting isn’t generic American small-town; it’s specific to Orient through and through.

“It really couldn’t have been a book that happened anywhere,” he explains when I meet him for a chat in the bar of his hotel in Bloomsbury. “It grew out of this specific place that was so weird and intriguing, and hadn’t really been written about before.”

Plum Island, a small landmass just off the coast of Orient that’s home to a government animal-disease centre, was the setting for Nelson DeMille’s 1997 eponymous murder mystery, but Bollen’s novel is the first story that turns its attention to the hamlet itself. He came up with the idea of setting the novel there while staying in the house of friends of his in the real-life Orient while editing his first book, Lightning People. He spent a week there alone and found himself strangely frightened by the thick darkness that enveloped the house each night: “I couldn’t believe how scared I was; I was shocked by my fright. I remember I took a knife to bed because I was so freaked out.” He became obsessed with the beauty of the setting by day compared to the stark contrast of this “nightmare by night” so he set out to capture this juxtaposition by turning the town into the setting for a murder mystery.

You can’t celebrate the fact that you can rent out your home in the summer for a zillion more dollars than before and drive prices up but then also want it to be a cloistered, safe community. You can’t have it both ways.”

“New York City has room for eight million novels about New York City,” he explains, “but there are some places that really only have three or four books in them until everything’s been used. I really wanted to write about Orient before loads of people moved there and it became just another place.”

We see this happening in the novel itself in the tension between the long-term ‘year-rounder’ residents and a new generation of interlopers from the city, buying up the old houses, thus reinvigorating the local economy but also bumping up prices in the process.

“These are very real problems that are facing Orient,” Bollen assures me. “You can’t celebrate the fact that you can rent out your home in the summer for a zillion more dollars than before and drive prices up but then also want it to be a cloistered, safe community. You can’t have it both ways.”

The Hamptons on the South Fork have long been a popular, and expensive holiday spot for wealthy Manhattan-dwellers, but it’s only in more recent years that vacationers have started to colonise the North Fork in the same fashion. The area became increasingly popular during the two years he was writing the novel, Bollen tells me, something that put him on edge as he rushed to finish writing.

“I felt like an early settler worried that new people were going to move in and take over. At one point there was a Girls episode set in Greenport [the town immediately across the causeway that separates Orient from the main body of the island], and I got so territorial. It’s stupid, I know,” he says with a laugh, “it’s not mine; I don’t even have a house there, but I had a certain investment in the place.”

The new arrivals in his book are all artists who’ve fled the galleried streets of Chelsea for the apparent freedom of a more rustic life outside the confines of the concrete jungle. This is a world Bollen is intimately familiar with; many of his closest friends are artists, he tells me, and he has much to do with the New York art scene in his role as Editor at Large for Interview magazine (the publication originally founded by Andy Warhol in the late 1960s).

“It’s interesting how artists have migrated out of the city. That long bohemian bastion of Manhattan is pretty much gone because it’s so expensive, and I think there is this sort of outbound flight to conquer and settle new places and build these artists’ communities. But I do find it deeply ironic and a little weird that people are moving back to these suburbs and country villages in an attempt to continue the free spirit.”

“It’s interesting how artists have migrated out of the city. That long bohemian bastion of Manhattan is pretty much gone because it’s so expensive, and I think there is this sort of outbound flight to conquer and settle new places and build these artists’ communities. But I do find it deeply ironic and a little weird that people are moving back to these suburbs and country villages in an attempt to continue the free spirit.”

One of the main reasons he wanted to write about the art world was the fact he didn’t feel like anyone had done a particularly good job of portraying it. He admired Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers, but “that’s set in the 1970s in a different art world entirely”, and although Ben Lerner touched on it convincingly in 10:04, Bollen felt that he wanted to do something different with it entirely: to take it out of New York.

“You can’t have someone sitting in a white cube at a front desk seriously without it seeming like it’s making fun of itself. It becomes like satire: someone wearing all black in a white gallery. But if you take these artists and you put them in a different setting, you can see what they’re like. It’s like taking specimens out of their natural habitat so they’re not camouflaged any more.”

With this context looming large in the background, in many ways Orient is actually very much a Manhattan novel. Long Island novels often are, Bollen explains, citing The Great Gatsby as the perfect example. Lightning People was definitely a New York novel. Set in the city transformed by 9/11, its protagonists struggled with loss and anxiety in the aftermath of this life-changing event. It wasn’t quite the novel people expected from him though, he thinks.

“I feel like when the first book came out everyone thought it was going to be very Bret Easton Ellis or Jay McInerney because of the world I had built from my work with the magazine and living downtown and all that. And I think I purposely didn’t write that book because I wanted to be taken seriously and I thought people were expecting me to write about this kid who goes out too much and has ennui. Now I kind of wish I had written that book,” he says slightly wistfully, before quickly snapping out of it. “No, if I had written that book at 23 it would have been ridiculously indulgent. At best it would have sounded wise but would have been filled with zero wisdom about the world. I was just too young. Obviously some people should write in their 20s, they have good ideas and ways of telling them, I just wasn’t there. I was still trying to work out what to write about that didn’t sound like someone else.”

If he surprised people with the first novel, he’s done the same thing with the second by writing a whodunit, not something his readers would necessarily expect after Lightning People or his journalism, but it was the form that he was attracted to, not to mention the fact that it’s a genre he’s a huge fan of. He started reading Agatha Christies in sixth grade, he recalls, and they became what he describes as his “gateway adult reading material.”

I was thinking about the fact that America is very much the home of the private investigator noir or the police procedural, and I realised while writing why this is. It’s because the chess board is already set up when it starts.”

That said, he wanted Orient to also work as a literary novel, which is does, successfully combining the pace and suspense of a murder mystery with the scope and breadth of something akin to a classic Great American Novel in the vein of Jonathan Franzen. The closest I can come to in terms of a direct comparison is Donna Tartt.

“I read The Secret History in high school,” he tells me when I mention her name, “and I loved it. I still remember the prologue; it’s just so smart. And I love how dark she gets with her characters. I wouldn’t think of her on a sentence-by-sentence level as someone I’m inspired by, but I think the mood that she gets down is something that I really like. She’s also interested in east vs. west, and I like that – Mills coming from California to New York, for example; these are little things that you don’t necessarily even think about when you’re writing it, but they open the story up.”

“I was thinking about the fact that America is very much the home of the private investigator noir or the police procedural, and I realised while writing why this is. It’s because the chess board is already set up when it starts – a murder happens right away or someone is missing and the PI or the police is on the case.”

He doesn’t go down this route in Orient though. There are a couple of police officers bumbling around in the background, but the people trying to solve the case are amateurs: Mills and Beth, an artist born in Orient but who’s only recently returned after years spent living in Manhattan; married and expecting her first baby she both belongs here but is an outsider attempting to fit in. She and Mills find kindred spirits in each other and quickly strike up a friendship.

“I needed to get the pieces on the board – I needed to bring Mills to Orient; I needed to explain why Beth is there, and why she’s unhappy and dissatisfied; and why they become friends. It’s a more organic process, but it’s also much slower.”

How was it to write a murder mystery, I want to know, was it daunting?

“Absolutely,” he says without hesitation. “I’m not some pro who has the formula down.”

Did you always know who it was going to be?

“I knew who had done it, yes, but I had no idea how or why, so I was sort of wandering, but that was the fun part, trying to figure it out while I was writing. I realised also that a lot of writing a murder mystery is not solving the mystery, it’s actually preventing the reader from solving the mystery. So a lot of what you’re doing is constantly smokescreening and card tricks, or distraction games.”

A fine balance between plotting a mystery that makes sense but isn’t too obvious?

“Exactly. There’s a certain kind of high-wire walking, and a bit of gamesmanship and game play, which I like. I’m really opposed to this idea that literature shouldn’t have a plot. I love plots. Someone always reels out the nugget, ‘But life doesn’t have a plot,’ and I’m like, ‘Yes, actually, it does – you’ve obviously never worked in an office as that’s basically one rootless plot after another!’”

Given Bollen didn’t know where his narrative was going, was only writing the novel part-time while still holding down his day job at Interview, not to mention the fact that the book is close to 600 pages, I’m impressed to find out that he wrote it astonishingly fast in only eighteen months; he’s convinced the form has everything to do with the speed though.

“I highly recommend a mystery of some sort because it really forces you to keep writing. I felt with my first book that I could have kept going forever, but a mystery gives you a framework and a motor. It’s a way to curb overwriting and directionless.”

He’s working on a new book, not a murder mystery per se, but definitely a thriller – what he describes as “more following it through to the end rather than the guesswork involved in a whodunit” – and he’s left Manhattan, and America, behind, setting it in Greece, on the island of Paphos.

“I was always obsessed with vacation books,” he explains. “Not books you read on vacation, but books set on vacation. You become this weird entity on vacation, you’re there for pure leisure and you become vulnerable because of it. You have no idea where the police are, or what to do in an emergency. You’re a strange being pulled away from your surroundings, and self-obsession is your point. You’re not really yourself, but you’re supposed to be more yourself. It’s always intrigued me.”

“I was always obsessed with vacation books,” he explains. “Not books you read on vacation, but books set on vacation. You become this weird entity on vacation, you’re there for pure leisure and you become vulnerable because of it. You have no idea where the police are, or what to do in an emergency. You’re a strange being pulled away from your surroundings, and self-obsession is your point. You’re not really yourself, but you’re supposed to be more yourself. It’s always intrigued me.”

Not that there’s much time for leisure in his schedule. He works 2–3 days a week at Interview, and dedicates the rest of his time to his writing. Would he want to write full-time, I ask? No, he doesn’t think so.

“I’m almost scared of getting closed off, and the magazine forces me to stay in the world. And I love having conversations with people, I feel like conversation is an art, and a lot of people don’t know how to do it.

“I also don’t find writing to be a joyous free feeling,” he tells me somewhat surprisingly. “I feel it’s a lot of work and very difficult. I’d almost rather work a day job so if there’s something for the magazine I’ll definitely do that instead. Fiction writing feels like factory work – you check in, like clock punching, and you have to do it – it’s not particularly enjoyable. It’s enjoyable in moments, but it’s more compulsion than anything else. I find it really compulsive. If I had children I wouldn’t hope that one day they spend all of their time crouched in front of a desk – days, months, years – I would hope they would do pottery or something like that instead!”

Orient by Christopher Bollen is published by Simon & Schuster in hardback and eBook. Read more.

christopherbollen.com

Lucy Scholes is contributing editor at Bookanista and a literary critic and book reviewer for publications including the Daily Beast, the Independent, the Observer, BBC Culture and the TLS. She also teaches courses at Tate Modern and Tate Britain.

@LucyScholes

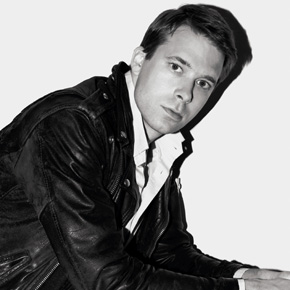

Author portrait © Danko Steiner