Civil rights and wrongs

by Lucy Scholes When James Baldwin died in 1987, he left behind 30 pages of letters titled Notes Toward Remember This House, an unfinished manuscript about the lives and deaths of three of his friends – Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. – civil rights activists, all of whom were assassinated in the space of only five years between 1963 and 1968. Baldwin began working on the project in the 1970s, the same decade during which he wrote and published The Devil Finds Work (1976), a searing critique of the racial politics of American cinema by means of his own first-hand experience as a viewer, and a text that will hopefully now rather belatedly become more widely recognised, not simply as an important work of film criticism, but a highly accomplished example of the genre at that.

When James Baldwin died in 1987, he left behind 30 pages of letters titled Notes Toward Remember This House, an unfinished manuscript about the lives and deaths of three of his friends – Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. – civil rights activists, all of whom were assassinated in the space of only five years between 1963 and 1968. Baldwin began working on the project in the 1970s, the same decade during which he wrote and published The Devil Finds Work (1976), a searing critique of the racial politics of American cinema by means of his own first-hand experience as a viewer, and a text that will hopefully now rather belatedly become more widely recognised, not simply as an important work of film criticism, but a highly accomplished example of the genre at that.

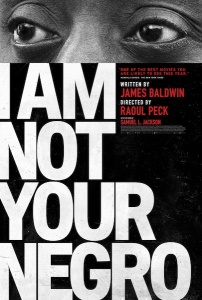

It’s these two texts – Remember This House and The Devil Finds Work – that provide the raw material for Raoul Peck’s visionary new documentary I Am Not Your Negro. Peck’s film, however, is nothing as simple as an adaptation of Baldwin’s works, nor is it a documentary about Baldwin per se – though a recent New York Times piece on the personal correspondence held by his archive, both that which is available for perusal and that which tantalisingly still remains off-limits, suggests the full story of the writer and social critic’s life would make for a fascinating biopic. Instead, and as crazy as this sounds given Baldwin’s been dead for thirty years, it’s perhaps best described as a collaborative project between the two men: a film by Raoul Peck, written by James Baldwin. As Peck puts it in the introduction to the companion book, when Gloria Karefa-Smart, Baldwin’s younger sister, first handed him the letters that constituted Notes Toward Remember This House, he knew immediately what to do with them: “A book that was never written! That’s the story… My job was to find that unwritten book. I Am Not Your Negro is the improbable result of that search.” Improbable it may be, but Peck has not only done the brilliance of Baldwin’s original work justice, but also produced a groundbreaking and thought-provoking work of art in his own right. It’s an intoxicating mix, as thrilling a piece of filmmaking in general as it compulsory viewing at this particular moment in time.

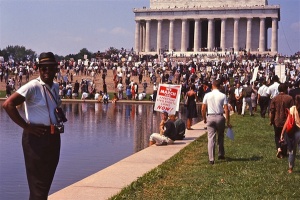

Peck takes the film’s literary history seriously, structuring it by means of chapters, and large passages of Baldwin’s original work are reproduced verbatim, via a voiceover from Samuel L. Jackson that provides something of a soundtrack to the various visuals shown on screen. These are a heady mix of archive footage – clips from films that Baldwin discusses in The Devil Finds Work; footage of civil rights activism; recordings of his three subjects; and stills from the violent encounters between African-American communities and the police that have continued to occur in what’s ironically referred to as the ‘post-civil rights’ era, along with images from more recent Black Lives Matter protests and the like.

Peck takes the film’s literary history seriously, structuring it by means of chapters, and large passages of Baldwin’s original work are reproduced verbatim, via a voiceover from Samuel L. Jackson that provides something of a soundtrack to the various visuals shown on screen. These are a heady mix of archive footage – clips from films that Baldwin discusses in The Devil Finds Work; footage of civil rights activism; recordings of his three subjects; and stills from the violent encounters between African-American communities and the police that have continued to occur in what’s ironically referred to as the ‘post-civil rights’ era, along with images from more recent Black Lives Matter protests and the like.

Over and over again, Baldwin tries to convince those he’s speaking to that he’s not there in the studio or the auditorium as a Negro, but simply as a man.”

Most striking of all though are the recordings of Baldwin himself speaking in public, from guest appearances on TV talk shows to speeches given at university unions – the rousing and clearly heartfelt standing ovation he receives from a room of all-white, earnest-looking students as uncomfortable as it is inspirational. He’s a formidable speaker; this much is immediately obvious, the elegance of his appearance, dressed in a dark suit, crisp white shirt and skinny tie, with a cigarette – that signifier of ’60s intellectual cool – in hand, matched only by the commanding eloquence of his words. All the same he’s clearly tired of being put in the position of having to discuss such glaring inequality over and over again. His beautiful, melancholic eyes look pleadingly towards his audience as if to ask ‘Why?’, but nevertheless he keeps his cool, even when presented with opponents like Paul Weiss, the pompous, white Yale Philosophy professor who suggests his interlocutor on The Dick Cavett Show is making too much fuss about the “race issue”.

If Weiss had listened to Baldwin more carefully, he’d realise the error of his own condescending over-simplification. Herein lies both the beauty of Baldwin’s analysis, and that of Peck’s ingenious and much-needed film. Over and over again, Baldwin tries to convince those he’s speaking to that he’s not there in the studio or the auditorium as a Negro, but simply as a man. “I’m not a nigger, I’m a man,” he declares, in one of the most powerful moments in the film. “But if you think I’m a nigger, that means you need it. And you need to find out why. And the future of the country depends on that.” Peck is too accomplished a filmmaker to do anything more than splice this message with images of racial unrest past and present. His point is made loud and clear: we need Baldwin more than ever today as sickeningly little has changed in the last half-century.

If Weiss had listened to Baldwin more carefully, he’d realise the error of his own condescending over-simplification. Herein lies both the beauty of Baldwin’s analysis, and that of Peck’s ingenious and much-needed film. Over and over again, Baldwin tries to convince those he’s speaking to that he’s not there in the studio or the auditorium as a Negro, but simply as a man. “I’m not a nigger, I’m a man,” he declares, in one of the most powerful moments in the film. “But if you think I’m a nigger, that means you need it. And you need to find out why. And the future of the country depends on that.” Peck is too accomplished a filmmaker to do anything more than splice this message with images of racial unrest past and present. His point is made loud and clear: we need Baldwin more than ever today as sickeningly little has changed in the last half-century.

To try to draw a dividing line between American citizens and their country is not the way forward. As Baldwin puts it: “The story of the negro in America is the story of America. It is not a pretty story.” Thus, the real genius of both Baldwin’s social criticism, and Peck’s animation of it onscreen, lies in this recognition of and insistence on examining the mythology of white innocence. This is where I Am Not Your Negro differs from recent documentaries about race relations in the US such as Ezra Edelman’s Academy Award-winning O.J.: Made in America or Ava DuVernay’s 13th. These films explain the inequalities of the present by means of bringing the past to light, and while Peck and Baldwin use the same tactic to initially approach their subject, the lasting message of I Am Not Your Negro is a reminder of just how much work is still to be done in terms of interrogating white privilege and power, and why projects such as poet Claudia Rankine’s proposed MacArthur genius grant-funded exploration of whiteness, the Racial Imaginary Institute, are the only way forward.

I Am Not Your Negro is in cinemas now, released by Altitude Films.

Lucy Scholes is a contributing editor to Bookanista and a literary critic and book reviewer for publications including the Daily Beast, the Independent, the Observer, BBC Culture and the TLS. She also teaches courses at Tate Modern, Tate Britain and the BFI, and hosts the monthly Bitch Lit book group at Waterstones Gower Street.

@LucyScholes