The age of nylon/Off the Azores

by Adrien Bosc

“A meditation on chance, destiny and the faults that lie sometimes in ourselves and sometimes in our stars.” Wall Street Journal

A vast confluence of causes determines the most unlikely result. Forty-eight people, forty-eight agents of uncertainty enfolded within a series of innumerable reasons, fate is always a question of perspective. A modelized aeroplane in which forty-eight story fragments form a world. An impromptu survey whose description goes beyond the very conformity of studies. A census of men, of women. A standard cross-sectional sample, as Charlotte Delbo wrote in Le Convoi du 24 janvier, the account of her convoy to Auschwitz – 230 women, 230 civil records, rows of facts, dates, places, which, by the plain power of their arrangement and sequence, are freed from the straitjacket of form. Lives, tiny and huge, matryoshka dolls. Six years earlier, Amélie Ringler could have been one of those women. She could have put a pile of tracts about the Resistance into her shoulder bag, become a political prisoner, been herded into the transit camp at Romainville, into the convoy, the extermination camp. Amélie would have been twenty-one years old. The city of Mulhouse was no longer Mulhouse but Mülhausen, in territory annexed by the Third Reich. Eighteen years old when Hitler and his retinue paraded through the streets. From the Schlucht Pass, the straight-armed procession of the Wehrmacht had wound its way into the old city. Within a few days, all the streets had German names. The rue du Sauvage (Street of the Savage) had become Adolf-Hitler-Strasse, a perfect translation that remained in place only long enough to spark general hilarity. The name was quickly changed to the more literal Wildemannstrasse. Twenty-two years old when, on the morning of November 21, 1944, she watched in astonishment as the Senegalese 6th Rifle Brigade and French troops entered the city under the command of General Lattre de Tassigny. Two days of fighting until, on November 23, the Moroccan 7th Rifle Company and a supporting tank unit captured the Lefèbre Barracks, the last German strongpoint.

*

Amélie is flying on the Constellation towards a destiny she hardly could have hoped for, an extraordinary opportunity, truly incredible, which she had greeted with total disbelief a few weeks earlier. A spool operator in a textile mill in Mulhouse, Amélie is the eldest of ten children. ‘Amélie’ is also the name of the potassium mine where her father works. North of Mulhouse lies a series of shafts named after Protestant heirs: Eugène, Alex, Joseph-Else, Fernand, Théodore, Max, Rodolphe. Her family lives in the workers’ village that the Mulhouse Industrial Society built near the mine works. Every morning, her brothers join her father in the potassium mines, while Amélie and her sisters work at the Dollfus-Mieg & Co. cotton mill – makers of the DMC yarns whose brand is posted on the storefronts of notions shops. The Ringler sisters are spoolers in the production of mouliné, a yarn whose cotton threads can be separated indefinitely. Spools, balls of yarn, skeins, carded and combed, put up in hanks, destined to be threaded through the eye of an embroidery needle. At Amélie’s cradle, no hidden fairy was present to foretell that the child would prick her finger on a spindle, yet her incredible story does include a godmother who watches over her fate. Amélie was in her twenty-seventh year when a letter of prophecy arrived. Her godmother had left Alsace for the United States in the 1930s. People knew she was rich, but no one imagined just how rich she was. She’d started as a worker in Detroit and become the director of a large factory for nylon stockings. A spinster and childless, she had focused all her energies on her career, and with her fortune now made, she was calling her goddaughter to her side. The whole family gathered on a September evening to read the letter from the almost forgotten aunt. Its message was not in doubt: Amélie was to be her sole heir. In the envelope was a money order for two hundred thousand francs to cover the cost of the trip.

No sound, no light or explosion troubles the island’s clear sky. F-BAZN has vanished into thin air. The two controllers on duty in the tower send out another call in vain. The line stays silent.”

Everything happened so quickly, and, at Orly on October 27, Amélie is still trying to take it all in. She wants the news confirmed firsthand; the prophecy still hangs in the air. It is her first trip, and she is sixteen thousand feet above an ocean she has never seen. The day before, in transit, she took advantage of some idle hours to wander through the Bon Marché department store. She bought a long green dress, a scarf, and a pair of nylon stockings from Schiaparelli. Amélie has long, dark hair, tied back under a black straw hat, her short fringe peeping out. Green, almond-shaped eyes. She wears a silver necklace with an Egyptian medallion, an ankh amulet, symbol of eternal life. Once inside Air France’s F-BAZN, she sits next to another young woman, Françoise Brandière. They are about the same age, could almost be sisters. While Amélie will catch a train to Detroit tomorrow at Grand Central Terminal, Françoise will board a second flight to Cuba.

Ten years later, Elsa Triolet would embark on her Age of Nylon trilogy – Roses à crédit, Luna-Park and L’Âme – sketching a period still in the process of defining itself, a moment when people’s outlooks, tastes and dreams were evolving. Amélie could have been one of the heroines of that narrative, a leading one. The cotton-mill worker, a future queen of nylon production, the spooler from Old Europe who becomes an industrialist in the New World. The passage from the age of silk to the age of nylon, from a living to a synthetic fabric.

***

Several minutes have passed since ground control last radioed the Lockheed Constellation. Palpable anxiety, the plane should already be taxiing on runway number one at Santa Maria airfield. No sound, no light or explosion troubles the island’s clear sky. F-BAZN has vanished into thin air. The two controllers on duty in the tower send out another call in vain. The line stays silent. At 2:53 a.m. the alarm is raised. The searchers focus first on the expanse of sea around the Azores. The Constellation has foundered at sea, no other explanation is likely. “To founder at sea”, those maritime words, expressions, verbs…

To founder at sea, ply the seas, jump into the sea, take to the sea, go to sea, die at sea, toss a bottle into the sea, be drowned, swamped, lost at sea, carried off to sea, to harrow, scour, sail the Seven Seas, disappear at sea, crisscross the southern seas, drive towards, end up with one’s back against the sea, at the bottom of the sea, old salt, sea wolf, fortune of the sea, a high, a full, a low, a heavy sea, that retreats, lays bare, rises, roars, forms whitecaps, bites into, wears at, undermines, erodes the cliffs, washes the shore, sparkles, glitters, glows, subsides, goes glassy, retreats, foams, unfurls, crests and falls, an oily sea, a sea of ice, of sand, a secondary sea, a bordering sea, an inland sea, landlocked, cold, temperate, frozen, calm, angry, swollen, stormy, flat, tropical, Arthur Rimbaud’s star-studded and lactescent sea, the furious lapping of the tides, the sidereal archipelagos and the islands whose delirious skies are opened to the seafarer: Is it on these bottomless nights that the aeroplane falls asleep and enters exile?

The island’s rescue craft set forth on the ocean in search of the wreck and its survivors, as they hope, or its casualties, as they fear. Searchlights bolted to their bows, sweeping the reefs and the Atlantic as far as their beams can reach. A black night, the wail of the siren, the coming and going of the lights, and the steadfast fear, mounting as the minutes pass inexorably. One-thirty a.m. on the archipelago. The dawn that will reveal the sea’s vast tracts is still some distance off. There’s no trace of an aeroplane around the patrol boats furrowing the reefs and distant waters, no fuselage, no wreckage, no cry of distress shatters the silence; only the restless sea, the sound of motors, of waves being pounded, of water lapping against hulls. A resonant silence. The silence you hear when, perhaps no more than once, you make a night crossing, a deafening silence, massive, a sky that is empty and filled with stars, a paradox.

In his Almagest, a summation of mathematical and astronomical knowledge, Ptolemy offered the first analytical map of the celestial vault, identifying 1,022 stars and forty-eight constellations. In the Azores, after dusk, in an aeroplane named for a grouping of stars, forty-eight people go missing. At 2:00 a.m., 3:00 a.m., 4:00 a.m., 5:00 a.m., no sign awakens the Atlantic. Reflected in the infinite puddle are the Great and Little Bears, Orion, and Scorpio.

From Constellation, translated by Willard Wood

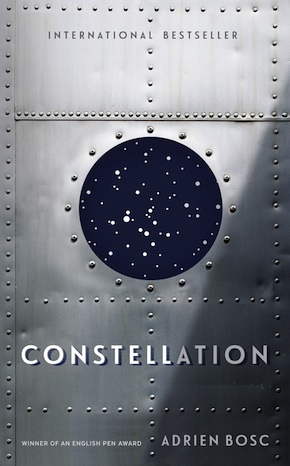

Adrien Bosc was born in Avignon in 1986. He is the founder of Éditions du sous-sol and the magazines Desports and Feuilleton. Constellation, his first novel, tells the true stories of 48 men and women who died in a 1949 French air disaster. Winner of the prestigious Grand Prix du roman de l’Académie française and a bestseller in France, Constellation is now published by Serpent’s Tail. Read more.

Adrien Bosc was born in Avignon in 1986. He is the founder of Éditions du sous-sol and the magazines Desports and Feuilleton. Constellation, his first novel, tells the true stories of 48 men and women who died in a 1949 French air disaster. Winner of the prestigious Grand Prix du roman de l’Académie française and a bestseller in France, Constellation is now published by Serpent’s Tail. Read more.

@BoscAdrien

Author portrait © Benjamin Colombel

Willard Wood is the translator of Yannick Grannec’s The Goddess of Small Victories, Jacqueline Raoul-Duval’s Kafka in Love and Anne Plantagenet’s The Last Rendezvous, among other works. He lives in Connecticut.