Diamond discoveries

by Katie Hickman

“A completely absorbing and delightful novel.” Amanda Foreman

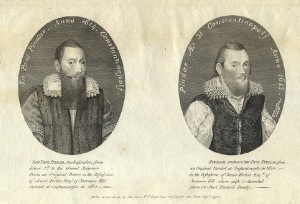

Not long after I began writing my Aviary Gate series of historical novels, I came across of portrait of Paul Pindar. It shows a narrow-faced, scholarly-looking man in his middle years. He wears a suit of sober merchant’s black, a falling collar of simple but exceedingly expensive white lace at his neck. The portrait is one of a pair, the other being that of his brother Ralph, an altogether stouter, bearded fellow, paler in colouring (for some reason I have always imagined him as having reddish or russet-coloured hair) and altogether more pugnacious in his expression.

Although it was not until the final book of my trilogy, The House at Bishopsgate, that I came to write about Ralph, Paul Pindar himself, an otherwise obscure seventeenth-century Levant Company merchant, has dominated my writing life for the last ten years.

Paul Pindar – a fictional version of a real-life merchant – became one of the central figures almost as soon as the project was conceived; in fact, I began to think of him as one of my ‘characters’ even before I began writing.

I was living and researching in Istanbul at the time. A friend, the historian and academic John Freely, had arranged for me to have a visitor’s pass to the University of the Bosphorus. Much as my present-day character, Elizabeth Stavely, would do at the beginning of The Aviary Gate, I went there every day to research in the English-language library.

I had gone to Istanbul knowing that I wanted to set a novel in seventeenth-century Constantinople, but beyond this my canvas was a blank. I was looking for an historical event on which to hang my story, a kind of springboard, as it were, into the past. With amazing serendipity, I soon found it.

The document was a copy of a diary written by a Yorkshireman named Thomas Dallam, a master craftsman who specialised in the making of musical instruments (his most famous creation was the organ in King’s College Chapel at Cambridge). At the tail end of the sixteenth century, Dallam accepted an extremely strange commission. He was charged by a group of Levant Company merchants to make a wonderful gift for the Sultan – the Great Turk – in Constantinople. The merchants, who included one of Elizabeth I’s first ambassadors to the Sublime Porte, Henry Lello, were attempting to renew their trading rights in the eastern Mediterranean.

I was looking for an historical event on which to hang my story, a kind of springboard into the past. With amazing serendipity, I soon found it.”

The etiquette at the Ottoman Court was that before any negotiations could take place they were required to present the Sultan with a gift. This could not be just any gift; it had to be something so marvellous and unusual that they could best their trading enemies, the Venetians and the French. Dallam more that delivered on his commission. He designed a wonderful mechanical toy, part musical instrument, part clock: a miniature organ topped by an enormous timepiece. When the clock struck the hour it triggered a device by which not only did the organ play a tune, but also two angels on either side of it sounded on their trumpets. Most amazing of all was a bush atop the clock, on which perched a crowd of artificial songbirds, which shook their wings, opened their beaks and sang a little tune. The Sultan was known to have an extensive collection of clocks, but the like of Dallam’s marvellous toy – so the merchants hoped – would never have been seen before.

Nineteenth-century double engraving depicting Sir Paul Pindar and his brother Ralph by William Thomas Fry. Wikimedia Commons

Dallam’s voyage to Constantinople is well documented in his diary. (It features, rather wonderfully, a shopping list of the things he packed to go with him, which included two viols – presumably for whiling away the long voyage.) After a six-month journey, he finally arrived there in August 1599, and was taken straight to the English ambassador’s residence. All the merchants, who had been cooling their heels at the Sublime Porte for more than two years, rushed to see it, including Paul Pindar, who was now secretary to the ambassador. The boxes were opened, but – horrors ! – they discovered that seawater had leaked into the packing cases during the voyage and the marvellous organ had all but rotted away. Their gift was ruined.

There was nothing for it but for Dallam to repair the organ. In order to do this he was granted special permission to construct it in situ in the Sultan’s Palace, the Topkapi. What happened while he was there is a famous story amongst Ottoman scholars. The Sultan himself was not there at the time, but residing at one of his summer palaces, and Dallam alleges that one day one of the janissaries who had been detailed to look after him called him to one side, and invited him to look through a little grille in the wall which led into the Sultan’s private quarters.

In the diary, published as The Account of an Organ Carryed to the Grand Seignor, and Other Curious Matter, 1599–1600, Dallam vividly described what happened next:

“… than crossinge throughe a little squar courte paved with marble, he poyneted me to a graite in a wale, but made me a sine that he myghte not go thether himselfe. When I cam to the grait the wal was verrie thicke and graited on bothe the sides with iron verrie strongly: but through that graite I did se thirtie of the Grand Sinyore’s Concobines that were playinge with a bale in another courte. At the first sighte of them I thought they had bene younge men, bt when I saw the hare of their heads hanging done on their backes, latted together with a tasle of smale pearles hanginge in the lower end of it, and by other plaine tokens I did know them to be women, and verrie prettie ones indeed… that sighte did please me wondrous well.”

When I read this I knew immediately that I had found my story. What would have happened if Thomas Dallam, or someone with him, had recognised someone amongst the ball-playing concubines?

It was this way that my character of Celia Lamprey was born. In The Aviary Gate, Celia became the (entirely fictional) bride-to-be of the real-life merchant Paul Pindar. I imagined Celia as the daughter of an English sea captain, whose ship had been attacked by Ottoman corsairs on her voyage to Constantinople to marry Paul, and was then taken into captivity and sold to the Sultan (an event which given the prevalence of piracy and the thriving slave trade throughout the Mediterranean was perfectly plausible. Besides which, the Ottoman sultans in this period did not marry, but selected a number of different concubines from women who were all, without exception, non-Muslim slave girls from a variety of different Mediterranean countries – they would only later have been converted to Islam).

Once Pindar realised that the bride he had assumed to be dead was actually imprisoned, under his very nose, in the Topkapi, what would he do? It would be certain death for anyone, let alone a foreigner, to admit to having knowledge of any of the Sultan’s women, and the trading mission was certain to end in disaster if it were discovered, but could he really do nothing to save her? In that moment, The Aviary Gate born, and the real-life merchant became not just an object of my historical research, but a fully-fledged fictional character.

After several years in Constantinople Pindar returned to Venice, where from the age of just nineteen he had worked as factor to an English merchant. From Venice, he was quite quickly appointed to Aleppo as Consul in his own right (this much is known about him from his entry in the Dictionary of National Biography).

Throughout the writing of the trilogy I was able to use hard facts about Pindar’s life and career to give strength and energy to my fictional character – and also as inspiration for my plotlines.”

What he actually did in Venice on his return is fictionalised in the second book of my trilogy, The Pindar Diamond. And what marvellous research trips those were! The last of the series, The House at Bishopsgate, picks up when he is living in Aleppo, on the eve of his voyage home to England. Due to the war in Syria, Aleppo is the only place where I was unable to carry out in-the-field research.

For an obscure merchant, Paul Pindar’s life is remarkably well documented. Throughout the writing of the trilogy I was able to use hard facts about his life and career to give strength and energy to my fictional character – and also as inspiration for my plotlines, since Pindar’s private life was characterised by a number of extremely exotic episodes. When he finally came home to London in 1611 he was an extremely wealthy man. A friend of Thomas Bodley, founder of the Bodleian Library in Oxford, Pindar had been asked to look for oriental manuscripts on his voyages abroad, and he was able to bring home with him a number of remarkable ones, mostly in Arabic and Syriac, on the subjects of astronomy and astrology in which he clearly had a scholarly interest (I have seen his bequest in the Bodleian myself, one of the very earliest in the library’s history).

Even more remarkable, however, was the collection of jewels he brought with him. The principal of them, a diamond valued at £35,000 – an immense sum in those days – was by all accounts so large it had its own name – Pindar’s Great Diamond – the wonder of which electrified London on his return. He is also known to have built himself an immense mansion, complete with gardens, orchards and a gatehouse, on the outskirts of the city walls at Bishopsgate Without, an area which in those days was still semi-rural. Many hundreds of years later, when the house was pulled down to make way for the new railways (specifically, Liverpool Street Station) its marvellously carved oak façade was preserved in what is now the Victoria & Albert Museum, where it can be viewed to this day. A pub, The Paul Pindar’s Head, is the only clue to the former location of this stately demesne.

The House at Bishopsgate follows the fortunes of Pindar, Celia Lamprey, Celia’s friend Annetta from her harem days, and her lover, Pindar’s servant John Carew (the latter three all entirely fictional). It is a story about love, loss and sexual jealousy, set within the extraordinary confines of Pindar’s great mansion which he filled, like a cabinet of curiosities, with treasures and furniture from the Orient.

The Aviary Gate, The Pindar Diamond and The House at Bishopsgate have taken me more than ten years to research and write. Their stories took me to Oxford, Bishopsgate, Istanbul, Venice and Damascus. But most of all they took me into the life and times of Paul Pindar, sometime merchant of the Honourable Levant Company, a man in a sober black velvet suit and a falling lace collar. I sometimes wonder what he would have thought if he could have known that almost exactly five hundred years after his death, his life would become so rich an inspiration for a historical novelist’s imagination.

Katie Hickman’s highly acclaimed Aviary Gate series has been translated into nineteen languages. She was shortlisted for the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year award for her first novel, The Quetzal Summer, and for the Thomas Cook Travel Book Award for Travels with a Mexican Circus (originally published as A Trip to the Light Fantastic). She is also the author of bestselling history books Daughters of Britannia and Courtesans. The House at Bishopsgate is out now from Bloomsbury in hardback and eBook. Read more.

Katie Hickman’s highly acclaimed Aviary Gate series has been translated into nineteen languages. She was shortlisted for the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year award for her first novel, The Quetzal Summer, and for the Thomas Cook Travel Book Award for Travels with a Mexican Circus (originally published as A Trip to the Light Fantastic). She is also the author of bestselling history books Daughters of Britannia and Courtesans. The House at Bishopsgate is out now from Bloomsbury in hardback and eBook. Read more.

katiehickman.com

@PindarDiamond

Author portrait © Neil Bennett