Dorthe Nors: Voices in the mist

by Mark Reynolds

Author portrait © Simon Klein Knudsen

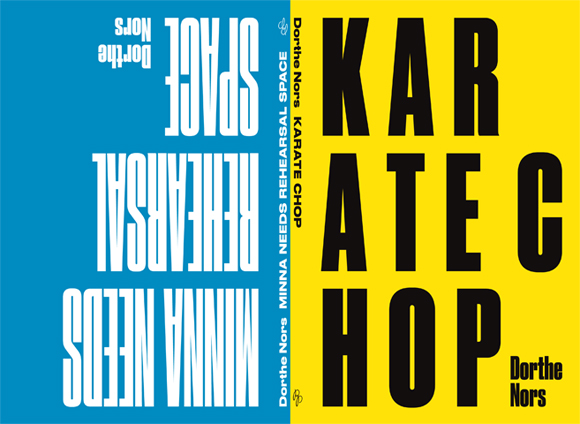

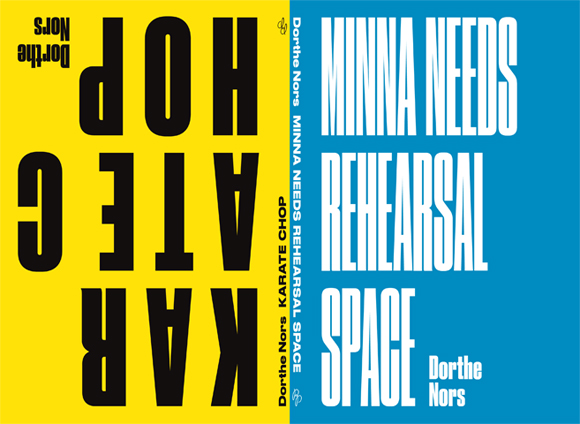

One of Denmark’s most inventive and acclaimed contemporary writers, Dorthe Nors’ story collection Karate Chop and her novella Minna Needs Rehearsal Space are now published together in a special back-to-back edition. Her spare, poetic, ominously disturbing stories present disconnected lives at critical moments of change – while the novella is a playful experiment in finding mood and meaning in the staccato prose of the newspaper headline or social media status update. We meet to talk about her UK debut, her home by the sea and growing older through the laughter.

MR: First of all, it’s a very striking format. Was it always planned to publish the two books together in one volume, or did the idea develop after the contract was signed?

DN: Immediately after the success of the story collection in America, Pushkin contacted my American publisher Graywolf and bought Karate Chop. Then when Minna Needs Rehearsal Space was translated soon after they met my agent at the London Book Fair and read it and said we’re going to do both, and then they came up with this format. There’s a French name for it, I don’t remember what but I’ve got to learn it [tête-bêche, meaning ‘head to toe’]. Now Graywolf are publishing Minna Needs Rehearsal Space and another novella of mine in 2016, and they’re going to do it like that, so it’s spreading.

Out of interest, how does the eBook work? I’m imagining people having to turn over their e-readers to switch between the two…

I have no idea, what a good question. I don’t read eBooks myself, so I haven’t asked. That would be so funny if you could make it so that each day the other manuscript is on top, and no matter what the reader does it will keep turning!

Graywolf describe the stories as “a mix of A.M. Homes, Etgar Keret, and Mary Gaitskill.” Do you identify with or enjoy reading those particular writers?

I didn’t know any of those writers before I wrote the stories. My insight into American literature was not good before this whole thing happened. I did have a reading with A.M. Homes in America a year ago. She’s an extremely funny person, she’s hilarious. I think one thing I could say we have in common is that we both like to have readers laugh on one page and sob on the next; to touch that emotional centre in the reader where sorrow and joy walk hand in hand. I was urged to read Etgar Keret last year by the Greenlight bookstore in Brooklyn, and I see a lot of resemblance there; the tightness of the form that I really like, to have the maximum effect by doing less. I definitely share something with him. I haven’t read Mary Gaitskill yet. I’ve been compared to so many different writers in America, and most of them I don’t know. But someone compared me to Flannery O’Connor, and I do see a resemblance there, and that’s because she’s quirky, she’s weird, she has that Southern Gothic darkness which is pretty Scandinavian, there’s something awkward brewing.

“Unsettling and poetic… Some pieces are oddly beautiful; others are brilliantly disturbing.” New York Times Book Review

I read in The Paris Review that you wrote all the Karate Chop stories in a two-week burst. Is that true? If so, how did that come about?

It was half of them, seven of them. I borrowed a summer cottage on the west coast from an old poet, and I was there for two weeks, and I must have been in the zone because it was just working and it was fun. Some of the stories have pretty horrible content – sadness and sorrow and violence – but I had so much fun because I could hear the voice was working, and what I did actually worked on paper. I’d take a walk by the beach and then I’d go home and in thirty minutes I had a story. When I work in a short form I write things very fast, because it has to have the same kind of vitality from beginning to end. If you write a novel, no one expects it to have the same level of intensity from beginning to end. Part of a novel’s inner structure is that it wavers, it differs, sometime it’s low-key and then it’s pitched high. But in a short story, or the short shorts that I write, you can’t lose your voice in the middle, so it’s natural that they were written pretty fast. But that I wrote seven of them in a row was pretty unusual. I was a little bit in love at the time, and maybe that kind of energy and intensity had something to do with it. My first novel I actually wrote in five weeks. I’ll never do that again, never, I don’t think it’s a very good novel. But fast writing definitely works for the short form.

How much later did you write the other stories in the collection?

I wrote the stories in this book over six months. Then came the big puzzle of putting them together in the right order. It’s a very touchy thing with short story collections, to actually have them build up in the right way.

Two of my favourite stories, ‘Female Killers’ and ‘She Frequented Cemeteries’ are very different in mood and scope. The first is from a male perspective and all about interior paranoia and fear; the other is distinctly female and about escape in the outside world.

How interesting, you couldn’t have picked two more different stories. This collection has been read by so many now, and people have very individual feelings about the stories. I don’t think there’s a story in the collection that I haven’t heard someone say, “I like this one the best.” Just because it mirrors something, it gets some sort of personal connection with the reader, which is lovely because that’s where literature happens. It doesn’t happen on the page as much as it happens over there in something I can’t control. But I like ‘She Frequented Cemeteries’ too, it has a very soft beat.

You keep your readers guessing about your characters’ state of mind and reliability. Is part of your own enjoyment of reading to have your instincts and preconceptions challenged?

Yes, and I like to be surprised while writing. Suddenly one day it hit me that in some of these stories it’s like the reader is in a mist, and out of this mist comes a face and a voice that tells us a very intense, short story, a fragment of life or a moment, and then withdraws into the mist again. And that has a huge impact on us because we feel we’ve been introduced to something extremely personal, but we haven’t seen the rest, it hasn’t emerged from the mist. An extremely dramatic effect comes from that, keeps us curious as to what else must be in there. And also it’s the minimalist tradition. Denmark has a very strong minimalist tradition right now, that the less you tell, the more you engage the reader, because to fill in the blanks calls for involvement from the reader, and I really like that. And I like that they fill in the blanks in all kinds of ways, and I definitely get surprised sometimes and I think, “Oh God, I’m a sick bastard, how could I come up with that? That’s weird.”

The stories also read something like modern parables; warning readers to be wary of certain character types or behaviours or situations. Is that how they came to you?

That’s interesting, because the parables in the Bible are stories about existential structures, I would say, especially the New Testament, and Jesus as a storyteller was pretty good because it’s not dogmatic. I don’t like stories that tell people what to think or what to do, I don’t like political or religious stories, but I do like stories about the wisdom of existential structures. That’s a very Swedish thing, actually.

Why did the story ‘Karate Chop’ provide the collection’s perfect title?

Well, the Danish language only has 250,000 words. You have about 500,000. That means that one word can mean many things in Danish, and the Danish title, Kantslag, means four different things, so the poor translator was in trouble when he had to translate that. It means ‘rimshot’, which is when you’re playing the drums and the drumstick hits the head and the rim simultaneously. It’s also a chip of china – if you want to sell some very expensive china at auction and it has kantslag, you wont get that much money for it because a chip fell off it. And also it’s the word that means a battle that takes place on a borderline. Kant is an edge or a border and slag is a battle, and this is one of the reasons why I chose this, because my characters are quite often portrayed in that situation where they are going from one life situation to another, or they’re on the threshold of some kind of revelation – or in ‘Female Killers’, he’s on the threshold of losing his own morality and slipping into the realms of his mind where he can’t control his own being anymore. And the last one is, it’s short for ‘karate chop’. So the main reason we chose Karate Chop was that it tells something about the nature of the stories. They’re short, they’re to the point, they’re accurate and they’re fast. And in Danish it was the combination of the portrayal of characters in a situation where they had to choose or they were slipping across a line, and then the chop. Long story, but that’s the way Danish is. It’s tough for foreigners to pick up on what we’re actually saying from time to time.

“The funniest Danish novel I have read in a long time.” Information

Minna is written in the curt style of internet status updates and, although written in the third person, it closely matches internal thought processes – from selfish instinct to the daily interactions and irritations that get in the way of perhaps higher long-term goals. What was the attraction in writing the whole novella in these short, sharp sentences?

It all started with me creating the character Minna five or six years ago. She’s like an alter ego, and the whole idea was that you had to express yourself to the outer world in headlines, always in headlines. This is how journalism works. When you open a newspaper everything is in headlines, the subject first and then the action, and I thought, how can we tell stories that are still deep, profound and complex, and about our inner life, if we speak in headlines? Is that possible? And that would be fun for me to try. It had great reviews in Denmark. Some journalists decided to do the entire review in headlines to see if they could do it themselves. It was like a game. Hemingway said if you’re stuck in your writing, always write a true sentence, and a headline is a true, solid, good sentence. It was hilarious writing that book and to find there were ways of expressing that inner turmoil in a very, very public voice.

Ingmar Bergman’s memoir Laterna Magica (The Magic Lantern) is repeatedly quoted and clearly very meaningful to Minna. What is your own relationship to that book, and to Bergman?

I came across The Magic Lantern quite late in life. Not more than three years ago a friend of mine said I should read it and I just loved that book. He’s rude and he’s offensive, but more than anything he’s honest about his own life and his failures and his creativity. I loved it, so I read all the other stuff that he wrote. I actually like the writer Ingmar Bergman a little bit more than the cinematographer. I love his pictures, it’s not that, but in his writing he’s like Strindberg, Strindberg was his mentor, and you can see that he’s very, very good at writing lines and creating the dynamic of a scene. I love reading his screenplays as if they were pure literature. I love Ingmar Bergman, but maybe that’s because I’m a closet Swede, that’s the tradition I was trained in. Swedish was my major at university, so I kind of get their whole creative vibe.

Would you say that humour is markedly different between Sweden and Denmark?

The Danish sense of humour is very close to the British, it’s playful, it’s understated, it’s wry, ironic. I think Danes and the British have a lot in common with their humour. The Swedes are more serious, it’s much more Bergman. It’s the darkness up there, those eight months a year where they just stare into darkness.

Norwegians seem to respond to that slightly differently again.

They just go crazy. They do some moonshine in the back yard and then go skiing. They go into nature in a different way than the Swedes do, they just take to nature. I love Norwegians, I love all my brother people, I do, but we’re different. One thing we have in common, and I think has an impact on the art that we do, is that the winters are truly very bad and the summers are extremely bright, so we turn bipolar, there’s something in our mindset and culture that is very, very vivid and bright and uplifting and then very introverted because that’s the deal with nature up there. Danes are the lightest. We’re in the south so we get less darkness than the others, so we’re the playful little brother.

British viewers have developed a strong taste for Scandinavian TV dramas in recent years. Which of them do you particularly rate?

I guess The Killing and The Bridge are pretty big over here, and that’s Nordic Noir crime fiction spreading into television. I saw a little bit of The Killing, and apart from it having a very clear plot structure, which my writing doesn’t, I identify with that sort of dark, introverted, mood swing thing that Sarah Lund has going for her. There was a TV spot on the national news when I had the breakthrough in America, and they actually put a picture of Sarah Lund in there. This is what they love about Danish, this kind of angry femininity in a jersey. I don’t know if it’s that simple, but it’s a Scandinavian mood at least that both my literature and those TV series portray.

The winters are truly very bad and the summers are extremely bright, so we turn bipolar, there’s something in our mindset and culture that is very, very vivid and bright and uplifting and then very introverted because that’s the deal with nature.”

Does the name Nors link to old Norse myths and early language?

My last name comes from a little village called Nors up in northern Jutland, and I think it means something to do with an ocean bay, which is called a nor in Old Danish. It’s an old, old family name, like 500 years ago my ancestor was a priest in that village and had five sons and they all picked up that last name and went into the world. It’s an uncommon name in Denmark, but it’s not to do with the Norse myths.

You live in a small village on the coast of Jutland. How long has that been home, and what are its particular attractions compared with Denmark’s main cities?

I was born in mid-western Jutland and grew up there and studied at Aarhus, then lived for some years in Copenhagen, which I guess is where you have to live when you want to write and figure out what’s going on in the literary environment. So I went to live in Copenhagen but I didn’t thrive there. I really missed the grandness of nature, the sky, being close to the weather and to the seasons, it was a physical craving. I love big cities, but I’m not created to live in them for years. So I went back to Jutland last year and I recently bought a small house in a village on the west coast. I can see the dunes, and I have the North Sea hammering at my windows every day. God, I love it. And then sometimes enormous flocks of geese fly over my house. There are wetlands nearby and sometimes you just have to stop working and listen and you can hear them talk up there, 60,000 of them in the sky crossing my house. That’s happiness to me.

So have you lived through all four seasons already in the new house?

No, not in that house, I just moved there recently. But I grew up in that area and I always knew when the lilacs and the daffodils were blossoming, and I lost that in Copenhagen. I’d call my Mom and ask is the lilac over now? And she’d say, “God, girl, you’ve got to get out of that city. You don’t know when’s what any more.” So returning to that is a blessing.

How closely did you work with the two translators? Did Martin Aitken work on the full collection in one go, or did he start with a single story?

What happened was that the book came out in Denmark and had great reviews – and then nothing. There were no feature articles, there were no sales. Everybody said Hallelujah and then it dropped like a bomb. But then Martin contacted me, he was an assistant professor and wanted to be a literary translator, and asked if he could translate some of my stories and show them to publishers so they could see what he can do. So we did that, started out translating two stories, had them published in American magazines, and then we just caught on fire in America, they loved the stories and they just kept asking for them, so we translated them one by one. He would translate them, I would read through them and change a very small bit. He worked a lot on his own, and had a lot of other things going on. He’s a star translator in Denmark right now, very busy translating all the big names, and I got more and more work in America so I needed a translator that was flexible. Also I completely love being in the process of the translation. I love to be involved in it. And Misha Hoekstra, who did Minna Needs Rehearsal Space, is a writer and musician from the Chicago area who now lives in Denmark. He’d send stuff over all the time and we’d have debates and laughs and discuss things and he’s really funny. He’s also translating some stories for me now.

Which of your books will be the next to be published in English?

The novella Dage (Days) that I wrote between these two has just been translated by Misha, which is the one that will be out in America in 2016, and I’m writing another novel now that will probably be translated pretty soon after it’s published in Denmark. I guess that will be the future for my writing, that I write in Danish and then shortly after it will be translated. My first three novels will probably be translated at some point, but the problem when your backlist is being translated is you’re sort of stuck in your literary past. It’s complicated enough with a story from 2008, and going back to 2001 I’m kind of lost. What the hell was I doing in 2001? It’s like you’ve estranged yourself from the material to an extent that it becomes a problem. But one or two of them might be translated in the future, when I’ve got the time to go back there.

Are there common themes in your earlier novels?

Yes, I can see a thread in all my writing, and it is the kantslag thing, portraying people when they’re rocking the boat, when they’re in a state of transformation, struggling with self or with life decisions. The novel I think might be translated, Ann Lie, is about a girl who’s 19 who wants to stop time, to fix the moment so time doesn’t move. It took me three years to write it!

What has changed over the years is in the beginning I had a hard time unleashing my sense of humour, it’s like I thought if people laugh it’s tacky. The older I got my books have become funnier, there’s more and more humour in there. The first ones were more Swedish, I would say. Now I’m turning back into a Dane.

Which other Danish writers should we be reading?

I think you should read Helle Helle now she’s in English. She’s another one Martin Aitken has translated, and one of our very good minimalists. We also have this young poet that I find mesmerising, his name is Yahya Hassan. He has a Palestinian background and was raised in the ghetto, and at 18 years old he wrote a poetry collection that was so mind-blowingly good and surprising and so playful with the Danish language. He took some of the rhythm of his first language and clamped it onto the Danish. It’s amazing, and it sold over 100,000 copies. And he’s a star, I can tell you. He was a criminal, he was in and out of institutions all his life, and then he just came out with that raw, completely amazing voice. He’s awesome. I don’t think they sold his book in English yet, but I know it’s been translated. He’s also very controversial. He attacks his own background, he attacks Danish society, he kicks at everyone. Nobody is sacred. I was at a literature festival in Norway with him, and he has five security people around him all the time. He said, “I don’t give a shit. Two years ago it was people in the institutions covering me all the time, now it’s the special forces. The only thing that’s different is that these guys are carrying guns.” He’s so smart, and he gives such a hope for other voices. So those are the two that come to mind. Helle Helle because she’s here already and I would recommend her, she’s good! And Yahya Hassan because he must be. I imagine some publishers might be scared because he stirs up a lot of aggression in his path, but he should be out there in some form.

Finally, the Danish Prime Minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt is best known here for her selfie with Obama and Cameron at Nelson Mandela’s memorial service – and for being married to a Kinnock. What else should we know about her?

I don’t know if I think she’s the world’s best politician, but God, she’s strong. Ever since she’s been prime minister she’s been beaten on, spat on, called the most horrible things, she’s had people attacking her from all angles, and she’s still standing. That calls for something, that calls for respect that she hasn’t bailed, that she hasn’t said, “Go and run your little shitty country on your own, I’m out of here.” Because she’s a very European, a very international kind of politician.

I kind of like that selfie, because it was not like they planned for the whole world to pick it up. And the story behind Michelle Obama’s reaction is that the picture was taken in a surly moment. She was actually in on the fun, but if you look away like that and then – snap – it looks as if she’s upset. And really it’s just colleagues fooling around. At a funeral, which is perhaps not so good.

But Danish politics is bad. We’re having an election later this year and unfortunately I think everything is going to slide very far to the right or very far to the left. It’s like the common sense of politics in the middle deteriorated over those years. That’s not only her fault, it’s also the financial crisis and the way the other parties around Danish Labour have behaved. But I think there’s going to be a landslide election for the radical right, that’s what the polls are saying, and it makes me sob, it’s a horrible, horrible situation. I’m afraid she’s not going to be able to hold onto power, there are very strong movements on the far right, racist, driven by fear, and the healthy politicians we have are so scared of not winning the love of the people that they’re sliding with it. And the people who then react strongly against this sort of bad behaviour, they go to the far left, and societies that break apart like that are vulnerable, so I’m a little worried.

![]()

Dorthe Nors was born in 1970 and is one of the most original voices in contemporary Danish literature. Karate Chop/Minna Needs Rehearsal Space is published by Pushkin Press. Read more.

dorthenors.dk

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.