A fetching destination

by Noo Saro-Wiwa

“Magnificently achieves its aim of honouring a unified heritage while showing the remarkable range of creativity from the African diaspora.” The Bookseller

It’s not every day I find myself eyeing up pornographic imagery with a Chinese man and a veiled-up African Muslim woman. The three of us were gathered around a counter and inspecting some aphrodisiac pills, the packaging of which displayed a photo of a man (with what I pray was a prosthetic penis) in session with a naked woman. Seized by embarrassment, my ears grew hot and I developed a phantom itch on my nose. The Nigerienne customer, however, didn’t give a toss. She was here on a shopping mission and had little time to waste on coyness or prudery.

“Many, many,” the lady told the Chinese seller, using the international lingo for wholesale purchasing. She ordered a thousand packets of Brother Long Legs, secured a delivery date for the merchandise then walked off with her friend, chatting away in French.

I was on the ground floor of the Tianxiu building in the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou, a magnet for African wholesale buyers. Dotted around me were glass counters stacked with all manner of “sexuality enhancing” products, sold by Chinese people who stood by nonchalantly while I checked out their merchandise. I saw vagina-tightening gels, and “extra strong delay sprays for long-lasting excitement” and – most intriguing of all – a “high-grade professional female oestrus induction toner” called Spanish Gold Fly. The packaging of another aphrodisiac had Arabic script printed on it and a photo of a black man being ‘entertained’ below the waist by two white ladies. I scarcely knew where to put my eyes. The vendors slouched behind their counters and fiddled with their phones.

Very few things surprise Chinese manufacturers and wholesalers. They are the eyes and ears of the consumer universe. They know all our secrets and desires, and produce for them accordingly. Motivated by an all-consuming desire to make money (this non-Christian nation runs the world’s biggest Bible printing press, after all), the vendors in the Tianxiu building were unoffended by my camera and time-wasting inquiries. So long as they made sales at some point in the day I was free to snoop, prod and ogle to my heart’s content.

The second floor was the place to buy underwear… my favourite was the ‘Black Power Obama Collection’ with a photo of America’s finest president, fingers on chin, eyes gazing eruditely into the distance.”

And so I checked out “hip lift” massage creams and hair wigs and Brazilian weaves. Some of the Chinese vendors had adopted the African method of hissing to get my attention – “Hello, my sista,” they said, while showing me buttock-enhancing yansh pads and packets of Ginseng tea, formulated to strengthen one’s kidneys, supposedly.

click on images to enlarge and view in slideshow

The second floor was the place to buy underwear. Some of the packaging displayed faces of famous footballers that had been Photoshopped onto Y-front-clad torsos: an improbably buff Zinedine Zidane showed off his bulge. Buck-toothed Ronaldinho looked especially pleased to be wearing his 100% combed cotton singlet. David Beckham, meanwhile, sizzled in a white vest and briefs, his hand cupping his crotch. But by far my favourite was the “Black Power Obama Collection” – a pack of men’s underpants decorated with a photo of America’s finest president, fingers on chin, eyes gazing eruditely into the distance. In the free-for-all that is the China-Africa small commodity trade, matters of image copyright do not enter the equation. Just shift the product.

The second floor was the place to buy underwear. Some of the packaging displayed faces of famous footballers that had been Photoshopped onto Y-front-clad torsos: an improbably buff Zinedine Zidane showed off his bulge. Buck-toothed Ronaldinho looked especially pleased to be wearing his 100% combed cotton singlet. David Beckham, meanwhile, sizzled in a white vest and briefs, his hand cupping his crotch. But by far my favourite was the “Black Power Obama Collection” – a pack of men’s underpants decorated with a photo of America’s finest president, fingers on chin, eyes gazing eruditely into the distance. In the free-for-all that is the China-Africa small commodity trade, matters of image copyright do not enter the equation. Just shift the product.

China is Africa’s largest trading partner, an economic relationship that has grown significantly since 2000. China provided huge loans to the continent when the IMF would not. It built infrastructure projects to replace the haggard modernist monoliths that sprouted during oil booms and colonial times. New bridges, highways, airports, stadiums and presidential palaces. The poorest of African countries were granted zero-tariffs on a sizeable chunk of their exports to China.

In turn, Africans were allowed to enter China and buy the small commodities that our low-manufacturing economies don’t make or have stopped making. They began travelling here as traders on temporary visas, others settling there permanently. It is a relatively recent phenomenon in the history of global migration. For some, this relationship between China and Africa signified the start of a post-colonial epoch, free of Western mediation. No more finger-wagging ‘wypipo’ on their civilising missions. The Middle Kingdom’s refusal to criticise or moralise was music to the ears of sensitive kleptocrats in Africa as well as some commentators, who saw a refreshing simplicity in this deal, this New Amorality.

In turn, Africans were allowed to enter China and buy the small commodities that our low-manufacturing economies don’t make or have stopped making. They began travelling here as traders on temporary visas, others settling there permanently. It is a relatively recent phenomenon in the history of global migration. For some, this relationship between China and Africa signified the start of a post-colonial epoch, free of Western mediation. No more finger-wagging ‘wypipo’ on their civilising missions. The Middle Kingdom’s refusal to criticise or moralise was music to the ears of sensitive kleptocrats in Africa as well as some commentators, who saw a refreshing simplicity in this deal, this New Amorality.

While Europe narrowed its doors to Africans with non-essential skills, China offered a chance for Africans to live within its borders or visit on short-term visas in order to buy small commodities and other business. By 2008, up to 300,000 Africans were thought to be living in the southern city of Guangzhou, concentrated in an enclave known in the national media as ‘Chocolate City’ (Chinese geographical nomenclature of all kinds often being indicative rather than artful).

From the Tianxiu building I headed to the busy Guangyuanxi Road in the Sanyuanli district. The smell of Chinese-brand cigarettes and egg waffles thickened the air. Visa overstayers leaned languidly against the railings while their fellow sub-Saharans – the visiting traders – loaded boxes into taxis with contrasting verve. Two black men sat on roadside stools getting their shoes shined by Chinese women. The seventies buildings, the anglophone shop hoardings, the concrete flyover colonised by creeping vines, resembled many a city in Africa.

Such a melanin-rich environment was too much to handle for some Chinese folks, who expressed their discontent with a frankness bordering on the comical. Take, for example, the online reviews for the Donfranc Hotel, which is popular with African visitors. Translated from Google, one review was bluntly titled, “Here are blacks”. In another entry someone reported: “the hotel facilities are obsolete… the rooms are dirty, dimly lit, with no windows inside… guests predominantly black… ”

Such a melanin-rich environment was too much to handle for some Chinese folks, who expressed their discontent with a frankness bordering on the comical. Take, for example, the online reviews for the Donfranc Hotel, which is popular with African visitors. Translated from Google, one review was bluntly titled, “Here are blacks”. In another entry someone reported: “the hotel facilities are obsolete… the rooms are dirty, dimly lit, with no windows inside… guests predominantly black… ”

Those African hotel guests come to Guangzhou to buy goods, particularly clothes, because the Chinese have undercut textile production back home. I could see their stalls diagonally opposite Canaan Market, run by friendly Cantonese ladies.

Manning the corridors were fibreglass Vikings modelling kaftans and kufi hats; blue-eyed plastic children wearing Gucci knock-off T-shirts festooned with the kind of glitter that exfoliates your flesh on contact.”

The sight of them handling piles of African wax prints was to my eyes as culturally transgressive as those male shop assistants who handle ladies’ underwear in Saudi Arabian lingerie shops. But that’s the way of the world these days. Africa plays no part in the displaying of African attire either: manning the corridors of Canaan Market were white mannequins – fibreglass Vikings modelling kaftans and kufi hats; blue-eyed plastic children wearing faux-gold Africa-shaped pendants and Gucci knock-off T-shirts festooned with the kind of glitter that exfoliates your flesh on contact.

African buyers haggled with the Chinese for this stuff. It led to heated face-offs at times, due mainly to cultural differences. In Africa, bartering is an art form, performed with some banter and perhaps a smile. But some Chinese took it as a provocation. Africans haggle too much, they complained. Always want things cheaper!

“Nigerian market woman will pet you,” one Nigerian guy told me. “She will tell you why it is costing this much – the trouble with her business… The Chinese? They just charge you.”

The slightest hint of a negotiation sent certain Guangzhou vendors into a rage. I got a first-hand taste of this after requesting a discount for a rucksack. The shopkeeper reacted as if I had just pinched her arse. She was scary looking too: her fringe and pollution mask combined to cover her entire face save for two disgusted eyes. With shocking ferocity she waved me away, her calculator falling from her hand and clattering on the counter. End of discussion. I wasn’t even allowed to improve my offer.

I walked on. There was nothing the Chinese didn’t produce and sell, it seemed.

I walked on. There was nothing the Chinese didn’t produce and sell, it seemed.

Further down the road I could see that even Nigeria’s election paraphernalia accessories were being manufactured and sold in Guangzhou. Shop windows were plastered with election bunting for Nigeria’s two biggest political parties; bracelets proclaiming: “So-and-so 4 Governor”; stickers of election hopefuls such as Charles Kenechi Ugwu, whose face tilted righteously above the words: “The Lord’s Chosen… Divine gift to Nsukka people”. Rumour has it that the ballot papers for one of Kenya’s general elections were delivered to Nairobi with Xs already marked in the box for the ruling party. (I can believe it. While travelling in Kenya on trains built by the Chinese, I saw signs written in poorly translated ‘Chinglish’ – proof that the government had abdicated supervision at the most basic level.)

Next to the election paraphernalia were displays of Nigerian police uniforms and badges. To my surprise, the vendor gave me prices on request. It made me realise I could clothe my own fake police force if I wanted to. One wholesale order – no questions asked – was all I needed to ‘establish my authority’ on the streets of Lagos or Port Harcourt. Which was amusing but also alarming. That the apparel of such an important branch of Nigerian governance could be sold so casually in Guangzhou spoke volumes about the power imbalance between China and our Mother Continent.

In Africa, the Chinese have bought up huge tracts of farmland and mining concessions with the consent of the national leaders, but here in China, we and other foreigners aren’t allowed majority ownership of so much as a hole-in-the-wall food stall.

I stepped out onto the street again. A trio of Nigerian ‘market women’ walked past, wearing boubous and carrying bags of merchandise on their heads. Curly-mop hair weaves, eyebrows like painted caterpillars; dark lips contrasting ghoulishly against bleached skin. These ladies negotiated the streets of Guangzhou with the blinkered nonchalance of the business traveller. The vision of them sauntering along the road, butt cheeks dancing behind, could easily be transposed to their ancestral villages where, like their forebears, they might have trekked several miles to fetch water – a time-consuming task that drains productivity. Instead, they had ‘trekked’ halfway round the world to Guangzhou on a trip costing upwards of £5,000. It’s a long way to go to fetch life’s everyday items.

The more things change, it seems, the more things stay the same.

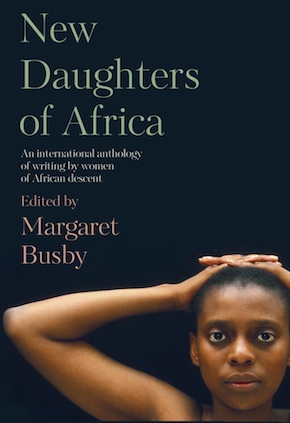

From the anthology New Daughters of Africa, edited by Margaret Busby (Myriad Editions, £30)

Photography © Noo Saro-Wiwa

Author portrait © Michael C. Wharley

Noo Saro-Wiwa was born in Port Harcourt, Nigeria, raised in England and is based in London. Her first book, Looking for Transwonderland: Travels in Nigeria (2012), was selected for BBC Radio 4’s Book of the Week, named Sunday Times Travel Book of the Year, and shortlisted for the Author’s Club Dolman Travel Book of the Year Award. She has contributed stories to anthologies and written book reviews, travel and other articles for publications including the Guardian, Financial Times, Times Literary Supplement, City AM, Prospect and La Repubblica. She was awarded a Miles Morland Scholarship for non-fiction writing in 2015. In 2018 she was among the judges for the inaugural Jhalak Prize for literature. She was awarded a Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Center residency for 2019.

noosarowiwa.com

@noo.saro.wiwa

@noosarowiwa

Author portrait © Luke Daniels

Margaret Busby was born in Ghana and educated in the UK, graduating from London University. She became Britain’s youngest and first black woman publisher when she co-founded Allison & Busby in the late 1960s and published notable authors including Buchi Emecheta, Nuruddin Farah, Rosa Guy, C.L.R. James, Michael Moorcock and Jill Murphy. An editor, broadcaster, and literary critic, she has also written drama for BBC radio and the stage. Her radio abridgements and dramatisations encompass work by Henry Louis Gates, Timothy Mo, Walter Mosley, Jean Rhys, Sam Selvon and Wole Soyinka, among others. She has judged numerous national and international literary competitions, and served on the boards of such organisations as the Royal Literary Fund, Wasafiri magazine and the Africa Centre. A long-time campaigner for diversity in publishing, she is the recipient of many awards, including the Bocas Henry Swanzy Award in 2015 and the Benson Medal from the Royal Society of Literature in 2017. She lives in London. New Daughters of Africa, showcasing the work of over 200 women writers of African descent, is out now from Myriad Editions. Read more