Fiction 2014–2015

by Lucy Scholes It’s that time of year again, so here’s my list of the best reads from the past twelve months, and some recommendations for a few titles to look out for in the new year.

It’s that time of year again, so here’s my list of the best reads from the past twelve months, and some recommendations for a few titles to look out for in the new year.

Starting with novels, and a title I would pick as my favourite of the year if pushed – Akhil Sharma’s Family Life (Faber). Sharma’s second novel took him an incredible twelve years to write but it’s well worth the wait. It’s a loosely fictionalised account of the tragedy that befell his family soon after they’d moved from India to the United States when his older brother suffered massive brain damage during an accident in a swimming pool. Sharma paints a heartbreaking portrait of a family pushed to breaking point and beyond, but his prose is absolutely meticulous throughout. He strips his writing back to the basics, getting rid of superfluous sensory descriptions, and the end result is not just astonishingly powerful, it’s genuinely innovative and original too.

Novels that demonstrate such authentic inventiveness are few and far between, but Sharma wasn’t the only one pushing literary boundaries this year. Rachel Cusk’s Outline (Faber) follows an all but nameless narrator as she travels to Athens to teach a writing course in the height of summer. We learn little about Cusk’s protagonist; indeed, the novel is more of a study of absence, female invisibility and silence than anything else. It’s a bold premise for a novel, even more so that the composition renders so acutely the idea behind the premise, but it works magnificently and makes for surprisingly addictive reading.

A similar meditation on female identity, albeit against the backdrop of a very different story, was Siri Hustvedt’s The Blazing World (Sceptre). Entirely fictional, but structured as the posthumously collated biography of a famous female artist who hid behind a series of masks, exhibiting her work under male pseudonyms in order to examine the inherent misogyny in the New York art scene, Hustvedt breaks down the boundaries between fiction and non-fiction, and continues to examine ideas of artistic containment that have appeared in many of her previous novels. She tells a wonderful story in collage form, so much so that I was a little surprised she didn’t make the shortlist for this year’s Man Booker prize. But then in my opinion, Outline should have won the Goldsmiths Prize for boldly original fiction rather than Ali Smith’s How to be both (Hamish Hamilton) – not that the latter wasn’t brilliant and mischievous in that particular Smithian vein. And as for Sharma, I think it’s a travesty he was left off the Man Booker list, especially in this first year of welcoming American authors into the fold. The fact that both Family Life and Outline have since made the list of 80 books nominated by the Folio Academy for this year’s prize is something of a silver lining, but we’ll have to wait and see whether either of them make February’s shortlist.

A similar meditation on female identity, albeit against the backdrop of a very different story, was Siri Hustvedt’s The Blazing World (Sceptre). Entirely fictional, but structured as the posthumously collated biography of a famous female artist who hid behind a series of masks, exhibiting her work under male pseudonyms in order to examine the inherent misogyny in the New York art scene, Hustvedt breaks down the boundaries between fiction and non-fiction, and continues to examine ideas of artistic containment that have appeared in many of her previous novels. She tells a wonderful story in collage form, so much so that I was a little surprised she didn’t make the shortlist for this year’s Man Booker prize. But then in my opinion, Outline should have won the Goldsmiths Prize for boldly original fiction rather than Ali Smith’s How to be both (Hamish Hamilton) – not that the latter wasn’t brilliant and mischievous in that particular Smithian vein. And as for Sharma, I think it’s a travesty he was left off the Man Booker list, especially in this first year of welcoming American authors into the fold. The fact that both Family Life and Outline have since made the list of 80 books nominated by the Folio Academy for this year’s prize is something of a silver lining, but we’ll have to wait and see whether either of them make February’s shortlist.

Four stunning novels from the latter half of the year that each impressed me greatly were Elena Ferrante’s Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, translated by Ann Goldstein (Europa Editions); Marilynne Robinson’s Lila (Virago); Michel Faber’s The Book of Strange New Things (Canongate); and Mary Costello’s Academy Street (Canongate).

For anyone who’s missed the #FerranteFever that’s doing the rounds on Twitter, or hasn’t read about the famously reclusive and elusive Italian author who writes under the name Elena Ferrante but is often assumed (preposterously, as far as most women readers are concerned) to be a male writer in disguise, I urge you to stop what you’re doing right now and pick up either the first of her Neapolitan novels, My Brilliant Friend, or the stand-alone The Days of Abandonment. Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay is the third in the Neapolitan series – the fourth and final volume has recently been released in Italy, and will be available in translation next year – that charts the lifelong friendship between two Italian women, Elena and Lila, who grow up together in a poor neighbourhood on the outskirts of Naples. Few can rival Ferrante when it comes to raw, desperately honest writing, and her portrait of female friendship – from the intimacies between them to the betrayals – is flawlessly conceived and richly executed.

For anyone who’s missed the #FerranteFever that’s doing the rounds on Twitter, or hasn’t read about the famously reclusive and elusive Italian author who writes under the name Elena Ferrante but is often assumed (preposterously, as far as most women readers are concerned) to be a male writer in disguise, I urge you to stop what you’re doing right now and pick up either the first of her Neapolitan novels, My Brilliant Friend, or the stand-alone The Days of Abandonment. Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay is the third in the Neapolitan series – the fourth and final volume has recently been released in Italy, and will be available in translation next year – that charts the lifelong friendship between two Italian women, Elena and Lila, who grow up together in a poor neighbourhood on the outskirts of Naples. Few can rival Ferrante when it comes to raw, desperately honest writing, and her portrait of female friendship – from the intimacies between them to the betrayals – is flawlessly conceived and richly executed.

Robinson’s Lila is also the third in a series of novels. Set in the (fictional) Iowa town of Gilead in the 1950s, although completing the trilogy Robinson began with Gilead and Home, chronologically the action of Lila happens seven years earlier. The young woman of the novel’s title wanders into the town never expecting to linger more than a while, but ends up marrying old Reverend John Ames, one of the town’s two pastors. It’s an elegant and spare study of precarity, full of a sort of feral energy, much like Lila herself. Both Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay and Lila are strong enough to be read as stand-alone novels, but reading them each as pieces of a bigger picture brings more satisfying rewards.

Writing in The New Statesman a few weeks back about the surprising amount of contemporary novels addressing the topic, Philip Maughan writes, “Religion, and Christianity in particular, has become mysterious again.” And I have to admit, I’m somewhat surprised that two of my picks of the year concern themselves so thoroughly with the topic. Lila presents a particular and very American notion of Protestant faith, but Faber’s The Book of Strange New Things does something rather different with the subject. The story told is that of an intergalactic missionary sent to the far-flung, newly colonised planet of Oasis to bring the Word of God to the native inhabitants. God’s messenger is Peter, and he and his wife Bea’s faith is so strong they’re prepared to endure separation from each other while he fulfils his mission. Despite his fears, what awaits Peter on Oasis is an evangelist’s dream: beings eager to be ministered to. Meanwhile God seems to have deserted his flock back on earth as the planet spirals into disarray, and Bea finds herself questioning her beliefs, while Peter, millions of miles away, is unable to help her. Ostensibly a story about religion, Faber writes astutely about what it means to be human. It’s a stunning achievement by one of the most interesting authors writing today.

Writing in The New Statesman a few weeks back about the surprising amount of contemporary novels addressing the topic, Philip Maughan writes, “Religion, and Christianity in particular, has become mysterious again.” And I have to admit, I’m somewhat surprised that two of my picks of the year concern themselves so thoroughly with the topic. Lila presents a particular and very American notion of Protestant faith, but Faber’s The Book of Strange New Things does something rather different with the subject. The story told is that of an intergalactic missionary sent to the far-flung, newly colonised planet of Oasis to bring the Word of God to the native inhabitants. God’s messenger is Peter, and he and his wife Bea’s faith is so strong they’re prepared to endure separation from each other while he fulfils his mission. Despite his fears, what awaits Peter on Oasis is an evangelist’s dream: beings eager to be ministered to. Meanwhile God seems to have deserted his flock back on earth as the planet spirals into disarray, and Bea finds herself questioning her beliefs, while Peter, millions of miles away, is unable to help her. Ostensibly a story about religion, Faber writes astutely about what it means to be human. It’s a stunning achievement by one of the most interesting authors writing today.

From the established to the new: Costello’s Academy Street is her first novel but demonstrates a talent rarely found in debuts. Her prose is reminiscent of her fellow countrywoman Edna O’Brien’s work, especially the early sections of the novel set in 1940s Ireland during her protagonist Tess’s childhood. Her subsequent emigration to America in the 1960s – where the “essential loneliness” that lies deep within Tess never leaves her, even amongst the busy streets of Manhattan where she makes a new life for herself – is rendered in such a way as to recall the work of Colm Tóibín. Costello’s writing is spare and elegant, and the story she tells moving in that ordinary, everyday way that tugs at one’s heartstrings – a worthy winner of this year’s Eason Novel of the Year prize at the Irish Book Awards.

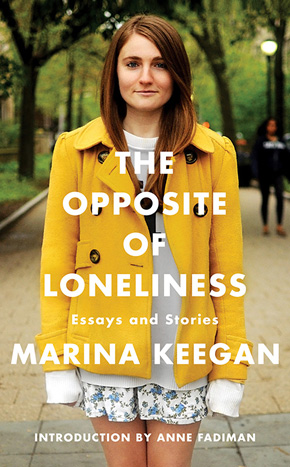

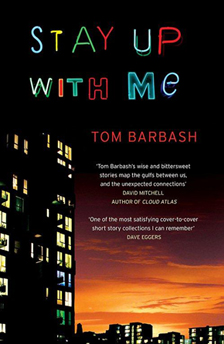

In terms of short stories, the work of two authors stood out for me. Marina Keegan’s The Opposite of Loneliness (Simon & Schuster), a posthumous collection of the author’s fiction and non-fiction, includes a deeply mesmerising and disturbing account of five people trapped in a pitch-black submarine 36,000 feet underwater: ‘Challenger Deep’. Also, the American writer Tom Barbash’s collection Stay Up With Me (Simon & Schuster), a volume of melancholy and disappointment in New York reminiscent of the original master of East Coast American suburbia John Cheever, from which we published the story ‘Balloon Night’.

In terms of short stories, the work of two authors stood out for me. Marina Keegan’s The Opposite of Loneliness (Simon & Schuster), a posthumous collection of the author’s fiction and non-fiction, includes a deeply mesmerising and disturbing account of five people trapped in a pitch-black submarine 36,000 feet underwater: ‘Challenger Deep’. Also, the American writer Tom Barbash’s collection Stay Up With Me (Simon & Schuster), a volume of melancholy and disappointment in New York reminiscent of the original master of East Coast American suburbia John Cheever, from which we published the story ‘Balloon Night’.

I could wax lyrical for several paragraphs about books I’m looking forward to in the coming year, but I’ve limited myself to picking one title for each month through to summer. Edith Pearlman’s new story collection Honeydew (Sceptre, January); film director, screenwriter, artist and actor Miranda July’s debut novel, The First Bad Man (Fourth Estate, February); Sarah Hall’s first novel in a while – though in the meantime she’s been winning awards for her wonderful short stories – The Wolf Border (Faber, March); and from Liza Klaussmann, author of 2012’s hot summer read Tigers in Red Weather, a Jazz Age follow-up Villa America (Picador, April); Lawrence Osborne’s Hunters in the Dark (Hogarth, May); and another story collection, Kate Clanchy’s The Not-Dead and the Saved (Picador, June).

Aside from Elena Ferrante’s fourth Neapolitan Novel, September will also see the publication of a new novel from American literary heavyweight Jonathan Franzen. Purity (Fourth Estate) is the story of Purity ‘Pip’ Tyler, a young woman on a mission to track down her absent father. Jonathan Galassi, the president of Franzen’s American publishers Farrar, Straus & Giroux, told the New York Times that this new novel will be a “stylistic departure” for the author: “There’s a kind of fabulist quality to it,” he told the newspaper. “It’s not strict realism. There’s a kind of mythic undertone to the story.”

At the moment I’m also darting between three proofs that immediately caught my attention when they dropped through my letterbox. The first, Deborah Johnson’s The Secret of Magic (Penguin, January), is set in the American Deep South in 1946. Regina Robichard, a young black Manhattan-based civil rights lawyer, finds herself in Mississippi investigating the murder of a decorated black soldier recently returned from Europe, at the behest of the reclusive author of a story of magic, murder and friendship that Regina loved as a child. The second is Jill Alexander Essbaum’s debut Hausfrau (Mantle, March), a story in the vein of Anna Karenina and Madame Bovary about domestic ennui suffocating an American housewife and mother married to a Swiss banker living in Zurich who fills her days with affairs. And finally, Elisa Albert’s no-holds-barred take on new motherhood, After Birth (Chatto & Windus, April), a book summed up by Emily Gould in such a wonderful quote, I don’t feel any need to add to it, apart from to say I’m 50 pages in and completely hooked: “This book takes your essay about ‘likable female characters’, writes FUCK YOU on it in menstrual blood, then sets it on fire. Then sets YOU on fire! Then giggles, then makes s’mores over your smouldering corpse.”

Happy reading!

Lucy Scholes is contributing editor at Bookanista and a literary critic and book reviewer for publications including the Daily Beast, the Independent, the Observer, BBC Culture and the TLS. She also teaches courses at Tate Modern and Tate Britain.

@LucyScholes