“We can fight with the mind”

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“A fascinating book… a timely reminder of the dangers of intolerance and the politics of hate.” Daily Express

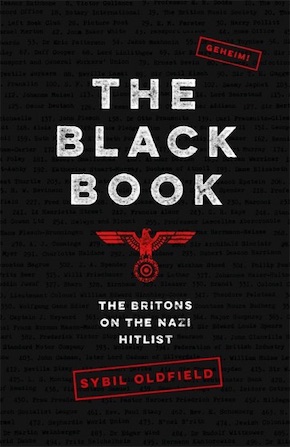

Sybil Oldfield’s The Black Book: The Britons on the Nazi Hitlist is, at first sight, an anthology of lives under terrible threat – a breathless, deeply personal, yet unflinching account of an impressive array of the many biographical journeys, the individual circumstances and diverse fates that earned 2,619 men and women an uncoveted place on the SS’s Sonderfahndungsliste G.B. (Special Search List Great Britain). More familiarly known as Black Book GB, this was intended as a supplement to the Informationsheft G.B. – “an introductory handbook on Britain for the occupation troops” – after a successful Operation Sea Lion. In short, it was a painstakingly massive proscription list, as lethal and as cunningly exhaustive as any devised in ancient Rome by Sulla or Octavian, and intended to spread infinitely more terror and devastation. It is (for the most part) Teutonically precise, competently clip, and sometimes even mystifying as far as the choice of certain public figures is concerned, or for its omission or exclusion of others. Once the only two surviving copies were discovered in Berlin in 1945, and this particular catalogue of “Germany’s enemies” was made public, to find one’s name there was an honourable distinction, as well as proof that one’s wartime allegiances might be claimed to have been on the right side after all, as Oldfield remarks with scholarly reserve on several occasions, yet also with unreserved irony. Reactions could be mixed and colourful: the cartoonist David Low retorted, “That is all right. I had them on my list too”; whereas Rebecca West is said to have written with a touch more phlegm to Noël Coward, “My dear—the people we should have been seen dead with.”

There was little vis comica in the book itself, however, and Oldfield’s tone has both momentum and monumentality as she displays and anatomises detail after detail, life after life, motive behind motive. Her Black Book is a protean and wondrous document, a fascinating and formidable piece of scholarship, a combative testament to those whom Oldfield calls throughout “heroes of humanity”. The term itself presages the dynamic energy in Oldfield’s use of words, stories, ideas: they are heroes not only on behalf of humanity, but also and especially thanks to that quality of human decency, integrity, intelligence, kindness and courage that she wishes to bring back to the foreground, especially in Britain, and very specifically today. They were “compassionate altruists who totally rejected the Nazi doctrine of righteous cruelty – ‘Haerte’ (hardness)… I am resurrecting them so that they may become once more an essential part of our collective memory, exemplifying at least in part of what it can mean to be ‘British’.” This is of course somewhat of a sleight of hand: “I deliberately include as ‘Britons’ those Jewish refugees who, stripped of their German or Austrian citizenship, would become ‘naturalised’”, in most cases after the war, as well as the many other foreigners on that ‘British’ list who remained in Britain for a time, some until the end of the war, but then chose to leave, principally for the US, West or East Germany and Palestine. Of the 2,619 names, at least 1,657 are refugees. At least 1,072 of these are Jewish.

Her conception of patriotism is reflected, incisive, insightful, critically receptive and alert, and aware of the complexities and intransigencies of history, and of human responses to historical forces and to everyday events.”

The assertion that “nationalism in every country is always appropriated by the far-right – but patriotism need not be” is a key driver in Oldfield’s project of resurrection, restoration and reorientation of our conscience and consciousness. Her conception of patriotism is reflected, incisive, insightful, critically receptive and alert, and aware of the complexities and intransigencies of history, and of human responses to historical forces and to everyday events. “Immediately after the defeat of Nazism and the unspeakable revelations of the extermination camps in 1945, anti-fascist resistance was claimed to be an essential part of the British DNA, ignoring the fact that it also had to combat some ‘appeasing’ pro-fascists in 1930s Britain.” The mass appeal of the British Union of Fascists, Chamberlain’s appeasement policy and the Munich Agreement, Ribbentrop’s not inconsiderable success with London’s salon society, the internment of German and Austrian refugees who had tried to warn the British government and public as to the true nature and intentions of Germany at the time, the many military decisions and international interventions whose clarity is still under study and debate, all these were blanketed, as Oldfield points out, under the momentous Spirit of the Blitz, the trauma of a Britain in ruins and in economic and social crisis, the immense manifold cost of an utterly devastating WWII and an emerging Cold War reality. Oldfield’s socio-political and historical analysis aligns itself on many levels with that of Nigel Copsey, who has argued that in Britain “anti-fascist attitudes became central to constructions of national identity, with animosity towards Nazi Germany and the heroic struggle against Hitler functioning as major sources of national loyalty and patriotic pride. [This] fusion of anti-fascism with nationalism reinforced perceptions… that fascism was essentially an alien creed inimical to British culture and traditions.” Copsey is highly critical here, even ironic, and Oldfield is keen to press the point even further: “However, all our anti-fascist forebears are dead and we cannot live off the moral fat of our endeavour. That self-serving myth of Britain as an eternally anti-fascist nation leaves our society blind to the danger of ultra-right extremism here and now.”

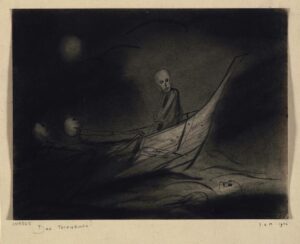

Das Totenschiff (The Ship of the Dead) by Fred Uhlman, ‘Internment’ series, Isle of Wight, 1940. Imperial War Museum Collections

The Black Book is therefore both a warning about the lethal toxicity of certain political models and a reminder of our own responsibility not to ignore the writing on the wall. It is not only a tribute to the many lives on (or off) the Nazi proscription list, but also a long, highly resonant philosophical essay and social treatise on right and wrong then and now, on historical necessity and agency, on the critical, life-or-death value of culture and civilisation against the pressures of völkisch ideologies and populist agendas. It is an unyielding manifesto on the choices one can and should make. She embeds in her discussion von Clausewitz’s psychological and political assessments of warfare and international relations, shifting, however, the centre of gravity from the famous “fog” and unpredictability of war and history, to the question of critical analysis and engagement, to the pivotal life instinct for constructive resistance to what undermines societal welfare and the common good, citing in this case Howard Caygill, who emphasises the central role held by “the possibility of the extinction of the capacity to resist” in Nazi thought and policy.

In the eyes of many, Germany’s defeat relegated the Black Book GB to the locus of a curio, a figment of maleficent Nazi delusion and megalomania. As Oldfield reminds us, however, the man who would have implemented the manhunt prescribed in its pages was instead deployed on the Russian front as head of Einsatzgruppe B, responsible for over 140,000 deaths. By a perverse twist of irony and historical justice, he would emerge unscathed from Germany’s own ruins, and serve only a token term of his Nuremberg sentence, before being employed by Porsche, with a double act as an intelligence agent for the US and West Germany. It is an unexceptional post-WWII ‘ambiguity’ or ‘blind spot’ and (once again) historical ‘necessity’, which only enhances the clinical brutality of the BBGB, and of the other similar “black lists” that were prepared for other nations which did come under German occupation. There, the ‘practical realism’ and pragmatic instrumentality of such projects would become horrendously attested.

Oldfield quotes extensively from declassified CIA files, Nuremberg trial records, archival sources, studies on the psychology of crowds and the socio-political dynamics of violence, as well as other historical sources and private memoirs, in order to create the ‘what if’ background of a Britain under Nazi rule. Her tableau is dramatic, highly textured, urgent and deeply nuanced, yet one cannot fail to ask why she did not draw the parallel between German plans for Britain, and German actions in conquered nations, which would have served to show the “banality” of German occupation practices, just as Hannah Arendt diagnosed them: the circumstances and conditions of a subjugated Britain would not have been exceptional; they would have been chillingly, horrifyingly, routinely and systemically part of a standard process of deculturation and dehumanisation…

The objective was to destroy everything that could sustain, remind or restore humanity itself, an explicit indication that the Nazis were fully aware that any modicum of true civilisation would be fiercely resistant to all they held dear.”

Who were the immediate, named targets for German occupation forces? Oldfield is formidably penetrating in her ‘systematisation’ of future Nazi evil. She gives us the categories of social belonging and endeavour that were deemed most undesirable, the taxonomies of humanity that had to be eliminated so that the New World Order could be installed on unshakeable foundations. How each category was populated is harrowingly indicative of the priorities and precepts of the Nazi model: the BBGB shows that its purpose transcended mere political convenience or the needs for ‘national’ security. The objective was to destroy everything that could sustain, remind or restore humanity itself, an explicit indication that the Nazis were fully aware that any mere modicum of true civilisation would be fiercely resistant to all they held dear. Oldfield creates brilliant captions for these categories, to brand them into our “collective memory”: the Nazis “gunned for” the Kindest and the Cultured; they “targeted” the British Establishment (which they attacked in a perverse appropriation of social discourse and, in their case, rather oxymoronic anti-Imperialist righteous indignation) as well as Political Figures left, right and centre; and they sought “to eliminate” Brilliant Minds in the Humanities and in the Sciences.

Nazi anti-elitism, anti-culture, anti-intelligence, anti-reflectiveness, their abhorrence of what Werner Jaeger would call Paideia, and the targeting of what they defined as elite dominant individuals or institutions, which they claimed suppressed the instincts and energies of the Volk, should make us pause, as Oldfield insists we do, in order to reflect on our own proclivity to create exclusionary and belligerently partisan categories and stereotypes of high and low, of traditions and countercultures. In our efforts to right wrongs, we should remember the Nazis’ ‘ideal’ reality, their satanic appropriation of paradigms and causes, their distortion of values, of social structures, of inalienable human qualities, that would bring about the effective dissolution of every possibility for beauty, wisdom, kindness, alterity, the mutual enrichment of past and future – simply and starkly put, the extermination of our very existence.

Oldfield has personal favourites as she tells the stories she selects for the sake of their tragedy, resonance and exemplariness. This gives her historical analysis an engagingly intimate, vividly conversational feel. In terms of perspective, hers is certainly a left-leaning framework, which is, nonetheless, unreservedly critical of Marxist absolutes and Soviet praxis. The principle throughout is dialectical engagement and understanding, appreciation, valorisation, human and academic integrity. In terms of particular blacklisted Britons and non-Britons, Virginia Woolf is clearly a favourite, and Oldfield rightly makes much of her letters, diary entries or essays, such as ‘Notes on Peace in an Air Raid’, published posthumously, where Woolf countered fascist might with mere sheer intelligence: her assertion that “we can fight with the mind” should perhaps be an equally memorable WWII phrase as any of Churchill’s historic aphorisms, or the more vernacular “Dig for Victory” or “Keep Calm and Carry On”.

The Quakers, Philip Noel-Baker, George Lansbury, Sybil Thorndike, Maude Royden, Edith Pye, Alfred Zimmern, the Bishop of Chichester George Bell, Eleanor Rathbone, Naomi Mitchison, E.M. Forster, Noël Coward, the Academic Assistance Council (renamed Society for the Protection of Science and Learning), Frank Foley and Thomas Kendrick, Victor Cazalet or Fred Uhlman and the library of Aby Warburg and its journey down the Thames, are examples of groups or figures that Oldfield is determined to resurrect. She composes highly dramatic biopics of those she considers of key interest, and there is here material for several exciting fictionalised biographies for any keen (and hopefully talented) novelist. One such, Conrad O’Brien-ffrench, would inspire Ian Fleming’s James Bond. “The most elusive chameleon, the most wily, brilliant secret agent of them all in this period, however, must, I think, have been Jona Ustinov – ‘Klop’, i.e. ‘bedbug’”, father of Peter Ustinov. Having started off as a Weimar intelligence agent until 1935, when he was asked to prove Aryan descent, he would become an MI5 spy under the cover name Middleton-Peddleton, with the singular distinction of being listed in the BBGB under both his real name and his alias. Those with an appetite for literary gossip will learn that H.G. Wells ‘inherited’ the lover of Maxim Gorky, the redoubtable and mesmeric Countess Moura Budberg.

To satisfy a plea by his daughter, Lord Croft made a perfunctory inquiry as to whether Uhlman might be liberated. It was as ineffectual as it was intended to be, and Uhlman remained a detainee.”

Yet the story that most articulates the complexities of Oldfield’s subject is that of Fred Uhlman, which she tells in some detail, yet not, one can argue, to the extent that it deserves. A lawyer who would turn painter in exile in Paris, where, as a Jew, he was not allowed to practise, Uhlman would become one of the ‘enemy alien’ internees when he sought refuge in Britain, penniless and knowing no English. Having met the aristocratic and rather unorthodoxly maverick Diana Croft, he would marry her barely two months after arrival, to the utter shock and horror of her parents. Sir Henry Page Croft, later Lord Croft, was Churchill’s Undersecretary of State for War, and had pushed from as early as 1939 for the internment of foreigners suspected of subversive sentiments, while castigating at the same time the imprisonment of members of the British Union of Fascists as unpatriotic and unjust. His sister Grace, Lady Edward Pearson, was herself a ‘blackshirt’ and an anti-Semite, deeply involved in the BUF and the British People’s Party, for which she was detained by the police. Her release, following her brother’s indignant intervention, would make the headlines and occupy several sessions at the House of Commons. To satisfy a plea by his daughter, Lord Croft made a perfunctory inquiry as to whether Uhlman might be liberated. It was as ineffectual as it was intended to be, and Uhlman remained a detainee, in a camp that was as much a desolate, alienating place of exile, as it was a thriving cultural community. His drawings of that period are exceptionally evocative and poignant, and they were published after the war in 1946. Raymond Mortimer would write in the introduction: “The uncertainty, the frustration and the indefinable anguish of captivity are reflected in the drawings… as he brooded over the fate of the world, from which he was isolated.” According to Anna Müller-Härlin, an expert on Uhlman’s art, his work would be “carefully stowed away and forgotten” in British and German museums. He is now known mostly as a writer, especially for his autobiographical The Making of an Englishman.

The rigour and emphasis on amplifying what sometimes are skeletal references in the BBGB also raises another issue that underlies throughout Oldfield’s project. The key concern is not simply why or how the Nazis targeted specific individuals or institutions, but also why and how multiple, evidence-backed warnings about Nazi Germany went unheeded and were suppressed, resisted even, with those who voiced them often marginalised or on occasion persecuted (the story of Ernst Toller merits a central place here); why documents such as the BBGB or Sidney Bernstein’s and Alfred Hitchcock’s documentary on the concentration camps were deemed “too incendiary [and were] concealed [by the FO] in the Imperial War Museum”, only released to public view much later. Ambiguities throughout, such as the Anglo-German Fellowship, “the degree of [potential] collaboration or resistance of British big business” towards German occupiers are a murky, uncharted territory, where, Oldfield says, “more research is needed”. “The recent opening of MI5 files has revealed that ‘probably hundreds of right-wing extremists joined [purported Nazi] networks… during WWII, unaware that they were run by British Intelligence, seeking to identify Nazi sympathisers in Britain.”

Unlike the Nazis who composed the BBGB, Oldfield herself does not believe in neat categories or strict academic boundaries. Her discussion throughout and her portraits of the people featured in it transcend historical topicality, specific politics, or individual storylines and fields of extraordinary achievement. The Black Book is a vastly urgent narrative of what, for Oldfield, constitutes human civilisation, humanity itself, as well as the indications or symptoms of crisis or dehumanisation. Her contextualisation and expansive dialectical theorisation of her subject is carried out with broad, audacious brush strokes, addressing everything from individual character traits to political ideologies, to the role of religious leaders and the agency of mere individuals, to the quality of societal building and government, with a particular emphasis on our understanding of one another, our duty towards others, ourselves, existence itself. This is a scrupulously documented survey, staunchly polemical, and socio-politically engaged. It is, above all, deeply human, and unabashedly focused on the spirit and the soul of the past as well as of the present.

Sybil Oldfield is half German and half English. Her grandmother was a pacifist feminist socialist who was placed under Schreibverbot during the Nazi dictatorship. Her mother was classified as an “enemy alien naturalised by marriage” in Britain after WWII broke out. Oldfield is now Emeritus Reader in English at the University of Sussex and a researcher for The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. A nuclear pacifist, she has campaigned on the psychological disarmament side of the anti-war movement since the 1960s. The Black Book is published by Profile Books in hardback and eBook.

Sybil Oldfield is half German and half English. Her grandmother was a pacifist feminist socialist who was placed under Schreibverbot during the Nazi dictatorship. Her mother was classified as an “enemy alien naturalised by marriage” in Britain after WWII broke out. Oldfield is now Emeritus Reader in English at the University of Sussex and a researcher for The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. A nuclear pacifist, she has campaigned on the psychological disarmament side of the anti-war movement since the 1960s. The Black Book is published by Profile Books in hardback and eBook.

Read more

@ProfileBooks

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

bookanista.com/author/mika