On finding your voice

by Lisa OwensWhen I first started actively pursuing a writing career, I had a pretty good idea of what I was going to write: spare and beautiful books set in rural Ireland, miniature domestic tragedies with universal truths at their heart. Possibly there’d be a PWDP (Priest With Dark Past), or a WRAUA (Woman Returning After Unexplained Absence). There would be a pub, a church. And there would be nature. It’s hard to do justice here to quite how subtly yet powerfully the natural world was going to mirror the rich inner lives of my characters. You’re just going to have to take my word for it.

I wanted to write the kind of books I loved reading: books by John McGahern, William Trevor, Colm Tóibín. Books full of quiet revelation and grace, where the modest limits and unassuming rhythms of life stood at odds with the epic yearnings of those who lived them. My parents are from Ireland, and though I’ve never lived there, I thought my credentials – Irish passport, frequent visitor – more than qualified me to step into this hallowed genre.

However hard I tried though – and I tried, waging daily battles with hedgerows and cows, burials and wakes – nothing took. It felt like trying to start a fire. I had all the tools: kindling, newspaper, coal, but whichever way I tried to arrange them, no matter how carefully I laid the foundations, prodded and poked, the initial flame simply refused to catch.

Weeks, then months, were lost to these attempts, five or six pages at a time involving beloved emigrant sons and resentful devoted daughters – garnished with some of that exquisite nature writing (it’s a travesty these efforts will never see the light of day) – before I gave up, opened a new document, and started the whole sorry process anew.

At the time, I was finishing up a Creative Writing MA and as these failures mounted, my final deadline loomed larger. I had just submitted another lifeless tranche of words to my supervisor, when I started, despondently, to scroll through the notes app on my phone, where I had for years been jotting down observations and scraps of dialogue.

In an act of wild desperation, I copied and pasted a handful of these into Word, and started to play around – expanding and rearranging, turning them into scenes – and suddenly I could see that I had… something. There was a story there, not just in the writing, but in the gaps in between, in the fragmentary, patchwork shape it was taking. There was uncertainty, there was amusement, there was a voice coming through, someone trying to make sense of things, of herself, of her place in the world.

But she did not till the land, nor silently yearn amid thin grey curtains of mist: she went to the big Sainsbury’s, entered competitions online and bickered with her boyfriend while cooking dinner. How dare she intrude on my timeless, lyrical masterpiece? Yet, where the other characters continued to elude me – obscured by overgrown brambles, studded with dark jewels gleaming in the dying sunlight – she stuck around, dogged and insistent.

There’s another way of writing what you know in a more instinctive sense: your understanding of human nature, of how people interrelate.”

Kill your darlings is a classic, if over-quoted piece of writing advice, and I wouldn’t dream of being so gauche and deeply unoriginal as to include it my own Tips for Writers. But since it has spontaneously come up, I do happen to have a (hopefully fresh) twist to offer. What if your darlings aren’t just words, your fire-starting similes, nature porn and so on – the flourishes and purple prose we all indulge in from time to time?

What if your darlings were also your cherished notions about what you want to write, how you think you should write, which authors you’d like to align yourself with? It’s more or less impossible not to be influenced by these things, and they can be vital points of reference to hold in mind. But if you find you are struggling to do the most crucial thing – to get life onto the page (to quote Claire-Louise Bennett) – it is worth being alive to other ways, to other stuff, however unlikely or unpromising it might first appear.

One reason I failed (this time) to contribute to the Irish Canon (Stark & Beautiful Division) was that I was ultimately trying to write books I’d already read. I didn’t have anything new to offer, and the voice I so desperately wanted to be mine was borrowed; I could only ever be an echo. The hurtling brooks and drifts of birds I was trying to summon were not really my brooks or birds: they came through a pre-existing filter, not my way of seeing, but a sort of idealised, collective other’s. So when I turned to the things I had idly noted down – the stuff that had occurred to me, in the moment, things that were odd or funny or striking in some other way, completely unfettered from my preconceptions about ‘literature’ and ‘readership’ – it was no wonder that stuff stood a much stronger chance of feeling alive and truthful on the page.

Just as I would never try to smuggle kill your darlings into any kind of writing advice, I can’t think of anything more mortifying and unimaginative than exhorting someone to write what you know – but actually, since that truism has also weirdly wormed it’s way in uninvited, let me see if I can cobble together a twist there too… Writing what you know can suggest a narrowing of perspective, a fearful, limiting approach to the endless creative possibilities at your disposal. But it doesn’t have to mean, write about yourself, or the facts of your life, or even that incredible thing your mum told you about the plumber’s neighbour’s cousin and the snake (even though it really is amazing and would make a great movie).

Those are all valid and often fruitful sources of inspiration too, of course. But I think there’s another way of writing what you know, where knowing isn’t about concrete facts, or details, or experiences you have necessarily had, rather, what you know in a more instinctive sense: your understanding of human nature, of how people interrelate. The things that you talk about with your friends, the themes that seem to recur in your conversations, the thoughts that go round on a loop at 4am. Whether your story is set in contemporary Britain, or on Mars in the year 2120, or, dare I say it, rural Ireland in the 1930s, this is the stuff that will catch, the stuff that will distinguish your work from everyone else’s.

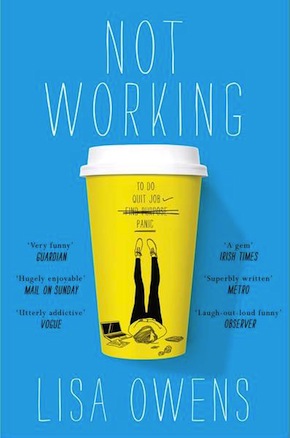

My book Not Working is far from the book I set out to write, and it’s also far from perfect, but it is mine. It has a point of view, and a voice that people might – or might not! – want to listen to. And it was only by letting go of everything I thought my writing should be that I could see not only what it was that I had to say, but also how I had to say it.

Lisa Owens is a novelist and screenwriter. Her debut novel Not Working (Picador, 2016) was a Radio 4 Book at Bedtime, and has been translated into nine languages. Her film adaptation of Days of the Bagnold Summer (based on Joff Winterhart’s graphic novel and directed by Simon Bird) earned her a Debut Screenwriter BIFA nomination in 2019.

Lisa Owens is a novelist and screenwriter. Her debut novel Not Working (Picador, 2016) was a Radio 4 Book at Bedtime, and has been translated into nine languages. Her film adaptation of Days of the Bagnold Summer (based on Joff Winterhart’s graphic novel and directed by Simon Bird) earned her a Debut Screenwriter BIFA nomination in 2019.

panmacmillan.com

@lamowens

Author portrait © Alexander James