Experience at full tilt

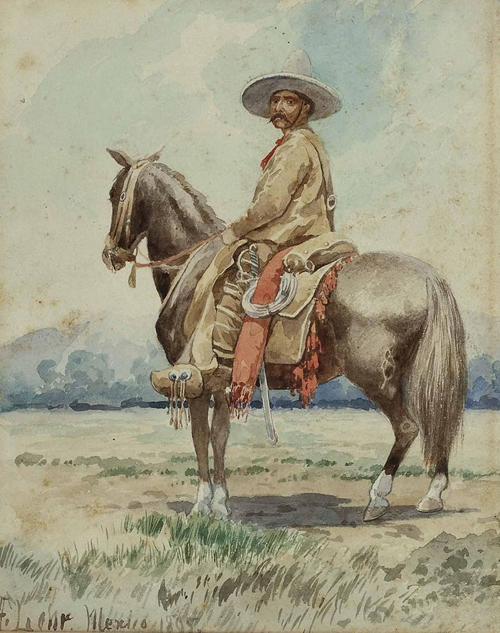

by Mika Provata-Carlone Gaucho by August Lohr, 1895. Wikimedia Commons” width=”290″ height=”367″>The particular richness and extraordinary power of Mexican literature are often lost, subsumed under the generic category of ‘Latin American Literature’. And yet there have been stories, epics, songs and poetry in Mexico well since pre-Columbian times. A Poet-King left to his people (and to its multiple conquerors) a legacy of words, a philosophical and literary tradition that has undergone rebirths and transformations, has sought tirelessly new directions and old roots, and especially a voice for the self as well as for a national identity. The names of the most celebrated male writers of Mexico are hopefully instantly recognisable and revered as part of the Latin American corpus and as major influences on European modernism and post-modernism, if not as the echoes of a particular people: Octavio Paz and Carlos Fuentes, Juan Banuelos, Roberto Bolaño, Martin Luis Guzmán and Juan Rulfo perhaps, or even Alfonso Reyes, José Vasconcelos Calderón, Augustin Yáñez, and Xavier Villaurrutia; certainly Diego Rivera, as well as Fernando del Paso, Guillermo del Toro, David Huerta.

Gaucho by August Lohr, 1895. Wikimedia Commons” width=”290″ height=”367″>The particular richness and extraordinary power of Mexican literature are often lost, subsumed under the generic category of ‘Latin American Literature’. And yet there have been stories, epics, songs and poetry in Mexico well since pre-Columbian times. A Poet-King left to his people (and to its multiple conquerors) a legacy of words, a philosophical and literary tradition that has undergone rebirths and transformations, has sought tirelessly new directions and old roots, and especially a voice for the self as well as for a national identity. The names of the most celebrated male writers of Mexico are hopefully instantly recognisable and revered as part of the Latin American corpus and as major influences on European modernism and post-modernism, if not as the echoes of a particular people: Octavio Paz and Carlos Fuentes, Juan Banuelos, Roberto Bolaño, Martin Luis Guzmán and Juan Rulfo perhaps, or even Alfonso Reyes, José Vasconcelos Calderón, Augustin Yáñez, and Xavier Villaurrutia; certainly Diego Rivera, as well as Fernando del Paso, Guillermo del Toro, David Huerta.

Mexico, however, also has a uniquely vigorous and rich genealogy of female authors, starting with the ‘Tenth Muse’, Juana Inés de la Cruz in the 17th century, to the astoundingly beautiful and arresting women writers of the 20th and 21st century, such as Elena Garro, who founded magic realism well before Gabriel García Márquez, Ikram Antaki, Nellie Campobello, with her more-fictional-than-fiction life; or Julieta Campos, Pita Amor, Leonora Carrington, Laura Esquirel, whose Like Water for Chocolate defined a generation of Western readers and writers, the startling Josefina Vicens, the infinitely inquisitive Valeria Luiselli, or Elena Poniatowska and Carmen Boullosa. And this is to name but a few.

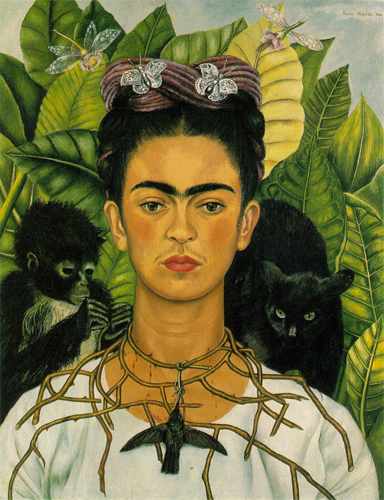

Mexican literature has always been polyphonic – it could not have been otherwise. Cultures meet and clash on any written page, time stretches and contracts, transgresses and interferes in every narrative. The quest, from pre-Colombian tales and chronicles to the most contemporary experiments and almost hypnotic literary experiences is for a concept of selfhood and national identity that allows unity as well as distinctiveness; which grants voice to memory as well as finding a speech for present and future. Mexican storytelling is like Brecht’s ‘To Posterity’, a torrent of pain, of deposed stories struggling violently to break free, to find a listener for “the terrible tidings”; and yet it is also about a different understanding of time and reality. It is full of nostalgia for mystery, sensuality and gentleness, for burgeoning fertility, for a vision full of colour, life and light that balances out death and dark times, as in the art of Frida Kahlo.

In his irreverent ‘Infrarealist Manifesto’, Bolaño identified:

“A new lyricism springing up in Latin America, nourishing itself in ways that continue to amaze us…. Tenderness like an exercise in speed. Breath and heat. Experience at full tilt, self-consuming structures, stark raving contradictions.”

Mexican writing is strong, unflinching, dastardly adventurous or mesmerisingly novel. From the essayistic and journalistic style of post-revolutionary novels it branched out to explore an infinite variety of hues and shades of expression, from the ethnological naturalism of the 19th century and the various “self-painted portraits of Americans”, to Vasconcelos’ Panamerican indigenism, his raza cósmica which would be an amalgamation of all ethnic groups in Mexico and beyond. The cost of cultural specificity, diversity and enriched distinctiveness did not concern Vasconcelo, yet it did awaken a sense of personal claim to history and to a national narrative in those who read him and argued with or against him. The ‘Revolutionary novel’ was the offshoot of this new consciousness, as well as the impetus behind post-1970s Chicano and Mexican-American movements seeking to assert a cultural reconquest. It also endowed Mexican writing with a transformative transcendental quality that possessed at the same time a strongly earthly, pragmatic and realist character. Combined with the native spiritualism, myths, cosmologies and philosophies, the possibilities for contemporary writers were endless.

Boullosa’s narrator drives us – like a vaquero – through the aimlessness of the world he forces us to face, understand and come to terms with.”

“A luminous writer” Miami Herald

Carmen Boullosa writes from within this Mexican tradition with a voice that carries echoes of every tension and wonder, every old or new piece of the puzzle she consciously tries to reconstruct. Her style in Texas: The Great Theft is a contrapuntal composition of many literary and non-literary forms. Interior monologue and nouveau roman, cinematic writing and surrealist (or ‘Infrarealist’) collapse of time-shapes, sequences or any linearity create a poignant flow of intermingling strands of many stories, picked up with what may only be termed unfailing random accuracy and precision. They conjure a world of related or simply co-existing planes of being, mutually elucidating or obfuscating whatever truth lies in them, reflecting above all the web that is human life. Her non-linear, non-European time is informed rather by the pre-Columbian notion of time layers which interface and can be omnipresent and ubiquitous – or simply absent. Her narrator moves in and out of past and present, back and forth between namelessness and omnipotence, from what was, what is and what is to come. Boullosa’s narrator drives us – like a vaquero – through the aimlessness of the world he forces us to face, understand and come to terms with, to simply nowhere, since there is no terminus, no conclusion or resolution, centre or margin. Only the narrator can dot the i’s and cross the t’s in this true fictional universe.

Boullosa’s story is the story of “good and evil in the 19th-century sense”, as she says in an interview with Vanguardia in 2013. The good is the recovery of Texas, the reconquest of identity and history via literature, as she makes clear. This good involves harrowing violence, unmitigated human tragedy. It exposes a dense fabric of hierarchies of racism and racial prejudice (both cruel and arbitrary), a ruling line of Gringos and Germans lording it over Mexicans, Kwahadi, Comanche and Lipan Indians, who in turn subject Hasinai Indians and Negros to slavery, and ruthless dehumanisation. There are even invisible people, like Werbenski the Jew, perhaps the only unspoiled human soul in the entire novel. Women are intriguing, powerful, unique, fiercely independent and resourceful, as well as brutally and bestially treated in a story which fictionalises the life and deeds of “Juan Nepomuceno Cortina, the Robin Hood of the frontier”, the military general and later diplomat who founded La Raza, the insurgent Mexican-Americans in the territorial conflicts with the US.

The aim of the narrative is explicitly rebellious. It is a declared reclaiming not only of what might be historical rights but also of what is certainly historical legitimacy, memory, the right to a narrative, even if it is a narrative of loss, disappointment and failure. “Texas, for us Mexicans was a future, a future that did not happen,” Boullosa says in the same interview, where she laments (and denounces) the dispossession of frontier storytelling from the Mexicans to whom it belongs: “American Westerns and the films of John Wayne captured all these images that belonged to us and which Mexico had been slowly forming during its 150 years of history; they constituted a romantic idea of the cowboy – yet they were ours.” She feels the despoiling to be not only territorial, but above all cultural: “They took away everything. As a matter of fact, the first flag of Texas was identical to the Mexican, green, white and red”.

Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird by Frida Kahlo, 1940. Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin/Wikimedia Commons” width=”230″ height=”299″>There is deep lush green in the landscape of Texas: The Great Theft; the white of oblivion, of a nebulous, pale and ghostly existence; and the scarlet red of bloodshed. This is a towering, brutally honest book by a quietly strong woman, a brilliant wordsmith and master storyteller. It is full of characters with significant names, personages of crime, illegitimate royal sons and stifled human hopes. It possesses crisp mordant irony – as in “It’s important to explain that Judge Gold is not a judge, despite his name; he’s in the business of stuffing his wallet. His métier is money. Who knows how he got his name” – and a trembling power to shock us, but especially to awaken our humanity as it is forced to witness total inhumanity: “Tim Black moves to see what’s happening. He doesn’t understand Spanish, which leaves him clueless about much that happens on the frontier, but no language is needed to know exactly what’s going on: a poor old man is being beaten senseless by the sheriff.” Or “Werbenski’s head is reeling, but he takes comfort in the fact that they baptized his boy. They may do what they want with a Jew, but my wife and my son must be saved”; “they have decided to sacrifice the Born-to-Run. It’s nothing out of the ordinary, and not worth us dwelling on. They keep his scalp and his magical jug. They depart camp ululating.”

Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird by Frida Kahlo, 1940. Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin/Wikimedia Commons” width=”230″ height=”299″>There is deep lush green in the landscape of Texas: The Great Theft; the white of oblivion, of a nebulous, pale and ghostly existence; and the scarlet red of bloodshed. This is a towering, brutally honest book by a quietly strong woman, a brilliant wordsmith and master storyteller. It is full of characters with significant names, personages of crime, illegitimate royal sons and stifled human hopes. It possesses crisp mordant irony – as in “It’s important to explain that Judge Gold is not a judge, despite his name; he’s in the business of stuffing his wallet. His métier is money. Who knows how he got his name” – and a trembling power to shock us, but especially to awaken our humanity as it is forced to witness total inhumanity: “Tim Black moves to see what’s happening. He doesn’t understand Spanish, which leaves him clueless about much that happens on the frontier, but no language is needed to know exactly what’s going on: a poor old man is being beaten senseless by the sheriff.” Or “Werbenski’s head is reeling, but he takes comfort in the fact that they baptized his boy. They may do what they want with a Jew, but my wife and my son must be saved”; “they have decided to sacrifice the Born-to-Run. It’s nothing out of the ordinary, and not worth us dwelling on. They keep his scalp and his magical jug. They depart camp ululating.”

Yet none of this is gratuitous, for all that it makes the experience of this novel a true tragic ritual. Boullosa’s narrator is Brecht’s man who is now left with nothing except an existence beyond despair:

“Even the hatred of squalor

Distorts one’s features.

Even anger against injustice

Makes the voice grow hoarse. We

Who wished to lay the foundation for gentleness

Could not ourselves be gentle.”

Boullosa has written a necrology as well as a testimonial narrative of lament and reminiscence and Samantha Schee’s translation is truly masterful, very resonant, deeply powerful; she conveys the uncanniness of the story unyieldingly and with actual gracefulness. “These gringos have eaten our pigs, our cows. They’ve even eaten our memories.” Thankfully, it seems that they forgot to eat the words with which to speak them.

Texas: The Great Theft is published by Deep Vellum.

Texas: The Great Theft is published by Deep Vellum.

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.