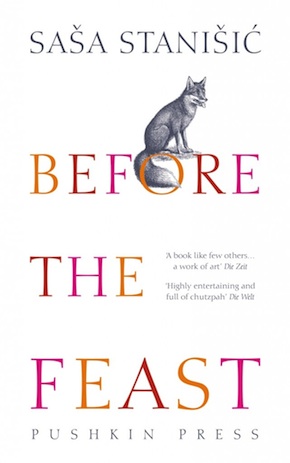

Greetings from Fürstenfelde

by Saša Stanišić

“Unforgettable characters, joyfully inventive storytelling… highly entertaining and full of chutzpah.” Die Welt

The vixen lies quietly on damp leaves, under a beech tree on the outskirts of the old forest. From where the forest meets the fields – fields of wheat, barley, rapeseed – she looks at the little group of human houses, standing on such a narrow strip of land between two lakes that you might think human beings, in their unbridled wish to grab the most comfortable possible place as their own, had cut one lake into two, making room right between them for themselves and their young, in a fertile, practical place on two banks at once. Room for the paved roads that they seldom leave, room for the places where they hide their food, their stones and metals, and all the huge quantities of other things that they hoard.

The vixen senses the time when the lakes did not yet exist, and no humans had their game preserves here. She senses ice that the earth had to carry all the way along the horizon. Ice that pushed land on ahead of it, brought stones with it, hollowed out the earth, raised it to form hills that still undulate today, tens of thousands of fox years later. The two lakes rock in the lap of the land, in the head of the land grow the roots of the ancient forest where the vixen has her earth, a tunnel, not very deep but safe from the badger, with the vixen’s two cubs in it now – or so she hopes – not waiting accusingly outside like last time, when all she brought home was beetles again. The hawk was already circling.

She would smell the earthy honey on the pelts of her cubs among a thousand other aromas, even now, in spite of the false wind, she is sure of its sweetness in the depths of the forest. She is sure of their hunger, too, their stern and constant hunger. One of the cubs came into the world ailing and has already died. The other two are playing skilfully with the beetles and vermin. But rising almost vertically in the air from a stationary position and coming down on a mouse is still too much like play. Their games often make them forget about the prey.

The vixen raises her head. She is scenting the air for humankind. There are none of them close. A warmth that reminds her of wood rises from their buildings. The vixen tastes dead plants there, too; well-nourished dogs and cats; birds gone wrong, and a lot of other things that she can’t easily classify. She is afraid of much of what she senses. She is indifferent to most of it. Then there’s dung, clods of earth, then there’s decay and chicken and death.

Chicken!

Behind twisted metal wires in wooden sheds: chicken! The vixen is going to get in to those chickens tonight.

It is never easy to get inside a henhouse… carrying eggs is all but impossible. Her previous attempts were failures, if delicious failures.”

Her cubs are staying away from the earth longer and longer. The vixen guesses that tonight’s hunt will be her last for her hungry young. Soon they will be striking out and finding preserves of their own. She would like to bring them something good, something really special when she and they part. Not beetles or worms, not the remains of fruit half-eaten by humans – she will bring them eggs! Nothing has a better aroma than their thin, delicate eggshells, because nothing tastes as good as the gooey, sweet yolks inside those shells.

It is never easy to get inside a henhouse. Even if no dog is guarding it, and the humans are asleep. She isn’t afraid of the fowls’ claws. But carrying eggs is all but impossible. Her previous attempts were failures, if delicious failures. This time she will close her mouth as carefully as she closes it on the cubs in play. This time she won’t take two eggs at once but come back for the second.

A female badger slips out of the wood. The vixen picks up the scents of bracken and fear on her. What is she afraid of? Bats fly past overhead. Taciturn creatures, moving too fast for any joking, fluttering nervously away. On the outskirts of the forest a herd of wild pigs is holding a council of war. They are unpredictable neighbours, easily provoked but considerate. Their scent is good, they smell of swampiness, sulphur, grass and obstinacy. Just now they are deep in discussion, uttering shrill grunts in their edgy language, butting one another, scraping the ground with their hooves.

A female badger slips out of the wood. The vixen picks up the scents of bracken and fear on her. What is she afraid of? Bats fly past overhead. Taciturn creatures, moving too fast for any joking, fluttering nervously away. On the outskirts of the forest a herd of wild pigs is holding a council of war. They are unpredictable neighbours, easily provoked but considerate. Their scent is good, they smell of swampiness, sulphur, grass and obstinacy. Just now they are deep in discussion, uttering shrill grunts in their edgy language, butting one another, scraping the ground with their hooves.

Their restlessness gets the vixen going. She trots off so as to leave those tricky creatures behind quickly.

The Up Above, roaring, brings thunder. It doesn’t like to see the vixen out and about. It is threatening her. Warning her.

***

We’re not worried. Electric torch, rain cape, gumboots and her umbrella: Frau Kranz is well equipped. In her little leather case, cracked, on its beam ends, a thousand and one expeditions old, are her watercolour paints, brushes, the old china saucer for mixing paints and some loo paper. For provisions: a cigar, a thermos flask of rum with some fennel tea in it, a sandwich. She carries her easel over her shoulders – Lada has built a little light into it specially for tonight. She has all you could need when you set out to paint on a night when it looks like rain.

“Does rum in fennel tea taste nice?” That’s the journalist. He’s been visiting Frau Kranz this week to write a column about her ninetieth birthday, for the weekend supplement, under the heading “We People of the Uckermark – the Nordkurier Introduces Us”, and he’s been firing off all sorts of other exciting questions, one H-bomb after another: homeland, hobbies, Hitler, hopes, Hartz IV social welfare benefits, in no specific order. “Yes, I’m afraid I really must have a photo, that’s non-negotiable; right, not in front of a tree, no, it wouldn’t be so good taken from behind; yes, I’d love some juice.”

Fürstenfelde everywhere. Small pictures, large pictures, serious, grey, brown, empty, post-war, festive, collective, rebuilding, new buildings, in the past, back at a certain time, a few years ago, today, at every season of the year.”

Frau Kranz is hanging out laundry in the garden. The journalist sniffs at a sheet.

“Let’s begin at the beginning. Your homeland and how you left it.”

“Good God.”

“I’d be interested to know how you felt, young as you were then, going here and there all over Europe in the confusion of wartime.”

Frau Kranz smokes a cigar, drinks rum tea with some fennel in it, has a little fit of coughing and takes the journalist round her house. Canvases all over the place. Fürstenfelde everywhere. Small pictures, large pictures, serious, grey, brown, empty, post-war, festive, collective, rebuilding, new buildings, in the past, back at a certain time, a few years ago, today, at every season of the year. Since 1945 Frau Kranz has been painting exclusively Fürstenfelde and its surroundings.

“Paysage intime,” the journalist remembers. He spent a year studying the history of art in Greifswald, before he broke the course off as being “too theoretical”. He sips his elderberry juice and makes a face. “Wow. Is it home-made?”

“Paysage intime,” the journalist remembers. He spent a year studying the history of art in Greifswald, before he broke the course off as being “too theoretical”. He sips his elderberry juice and makes a face. “Wow. Is it home-made?”

“It’s elderberry juice.”

“So you are originally a Danube Swabian.”

“I know.”

“Or to be precise, a Yugoslavian German.”

“What are you getting at?”

“Can we talk a little about that?”

“About the accident of birth?”

“We could talk about the Banat area. I’ve seen photos of it. Flat, rural, like the Uckermark. Did the similarity of the landscape help you to get used to living here?”

“No.” Frau Kranz makes very sweet elderberry juice.

“Right, and thinking back now do you sometimes feel homesick?”

Without a word, Frau Kranz leads the journalist into her bedroom, where a huge painting of nothing but rapeseed in flower shines all over one of the walls. The journalist, forgetting his question and also forgetting himself, delivers his verdict: “Like yellow rubber gloves for cleaning the loo, only prettier, of course.”

At last something on which he and Frau Kranz can agree. She pours him more elderberry juice; he puts his hand over his glass just too late.

We’re worried now. Frau Kranz walks down to the lake with a firm tread. We’re not happy about the evening dress she is wearing under her cape tonight. It doesn’t suit the night, it doesn’t suit her work, although it suits Frau Kranz herself very well indeed.

Last time she wore that dress was in 1977 in Schwerin, when she was given a certificate for artistic services to the Schwerin area in the category of painting, sub-category “The land and its people”. Frau Kranz went up on the platform, but she didn’t make a speech, she sang a song in bad Croatian. It was called “Polijma i traktorima” (In praise of fields and tractors), and one thing soon became clear: Frau Kranz does not sing well, but she does sing at the top of her voice, and what with that and the loudspeakers being turned up, and what with her ignoring the planned course of events, and a few men made more and more aggressive by the Croatian language and wanting to escort Frau Kranz off the stage after seven or eight verses when it looked as if the song was going on for ever, but some other men didn’t like their attitude and tried to protect Frau Kranz – well, what with all of that, there was a scuffle as background to the music that sounded like the roar of a rutting stag, and thinking it all over you can hardly imagine what a crazily wonderful evening that was for Frau Kranz in Schwerin in 1977. The certificate is hanging in her kitchen, rather yellow now from all the steam.

Why has Frau Kranz dressed up like that tonight, when she usually goes painting in the Fürstenfelde Football First Eleven tracksuit? On arriving at the ferry boathouse, she unloads her stuff and stands at the water’s edge. The ash trees breathe in her perfume. They know the smell of her. Frau Kranz unscrews her thermos flask, raises it to the boathouse, drinks and closes her eyes.

***

We are touched. Just at the right time for the Feast, one of those who have moved to the village, namely Frau Reiff, has tracked down our four oldest postcards and had them reprinted on good cardboard. The Homeland House can sell them and keep the money. Frau Reiff has given us the originals for the auction.

1. The War Memorial in the Friedhofshain: the year is 1913. It is an eagle on top of a rectangular column tapering towards the top. You can see the gravestones indistinctly behind it. It records the names of the dead in three wars: 1864, 1866, 1870. In the corner it says Greetings From Fürstenfelde.

It has survived the World Wars. The list of names from those two wars, as you might expect, is longer, and stands on extra stones beside the column.

2. The Shooting Range shows Fritz Blissau’s beer garden. The year is 1935, the village is celebrating the Anna Feast. The village has put on its Sunday best and is wearing a hat. Except for Gustav. Gustav is eight. But Gustav’s pudding-bowl haircut looks like a hat, so it fits in. A young woman is coming up from the left in the postcard, carrying a tray laden with drinks, although everyone has a drink already apart from Gustav.

Those are good years. There are 400 more of us than today. We leave the village from two railway stations and drive around in fifteen motor cars. Optimism procreates children. Gustav’s parents can afford a proper haircut for Gustav. His father is the pastor, his mother is a secretary at the telegraph office. The country people nearby regard us as townies. We believe in work and the Fatherland, we have work and the Fatherland, we wear bows in our hats. We are living in a condition of blissful ignorance. After the war we’ll be going around barefoot.

There’s a canopy of chestnut leaves above the shooting range. Gustav is sitting at his table alone. His father wanted him to be in the photo, and had to persuade Blissau, who doesn’t like to see children running round among his guests and his jugs. Gustav likes running round. He wants to be a geographer, like Hans Steffen. The Nuremberg Laws are six days old. The tablecloths are white.

The village looks at the camera. Only the young woman stares at her tray of drinks: please don’t let there be an accident now. It does us good to see you all looking so tense because of the photographs, while at the same time we can tell that you really feel relaxed.

Herr Schliebenhöner releases the shutter.

A bee settles beside Gustav’s hand. Bells ring. The sun seems to be shining above the chestnut leaves.

3. The Windmill: a beautiful tower with wide sails. Two cows are grazing in front of the mill. In the viewer’s imagination, the wind is blowing and the sails are going round. No one is indifferent to windmills. In the course of his life, every fifth male Federal German citizen will try to understand exactly how a windmill works.

Nothing is left of the mill today. The people in the new buildings hang out their washing to dry where it used to be. Silent Suzi’s mother hangs out her bed linen. The Bunny logo flutters in the wind and rain.

Nothing is left of the mill today. The people in the new buildings hang out their washing to dry where it used to be. Silent Suzi’s mother hangs out her bed linen. The Bunny logo flutters in the wind and rain.

Windmills are windmills, washing lines are washing lines. The village doesn’t say: oh, if only the windmill were still standing. The people from the new buildings are glad to have washing lines outdoors; their apartments are small.

But we’d like to talk about mills. There were four of them here. One was demolished in 1930, only the lower part of another still stands and is used as a second home at weekends by a married couple from Hamburg. The third dates from the sixteenth century. The feudal lord, Count Poppo von Blankenburg, was not at all happy about the flour it produced, and sent miller after miller packing. Finally he decided to try his luck as a miller himself. He took on three young miller’s men to help him, gave the priest living quarters in the mill to protect it from the Devil, and also hired a wise woman who promised to drive away mealworms and any ghosts haunting the mill (§ 109 of the Procedure for the Judgment of Capital Crimes, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V’s statute introduced in 1532, made it easy to distinguish between harmless and harmful magic). Finally he gave orders for three virgins to be brought to him. History does not relate what they were meant for.

The result was disastrous.

The priest and the wise woman went for each other first metaphysically, then physically. The miller’s men seduced the virgins, or vice versa, and when the village had no flour left at all, not even bad flour, its people assembled outside the mill to ask what was going on. The Count appeared at a window, shivering and shouting. How, he asked, was a man to get anywhere with a mill that felt like a human being and just didn’t fancy grinding flour?

He found that he could grind such fine, pure flour that at the Anna Feast, which was soon celebrated, the villagers hardly touched any meat once they had tasted the bread; in that place a wind turbine stands today.”

“Talk to it kindly,” called a small voice from down below through his ranting. “Be nice to it.” The speaker was a girl with blue-grey eyes and short blonde hair. The nobleman fell silent, and the farmers, the labourers with their pitchforks, and a fox who had come to see what there was to be seen here were surprised too. But then the people agreed with the girl. Perhaps they really thought it would help, but more likely they just wanted to hear how their Count went about beguiling the mill.

And he did it, too. He immediately turned to the mill’s shutters and began praising them lavishly. What beautiful shutters over its windows, whether they were open or closed! And its sails! So large and useful. And so on, although here we must point out that no one would know the story today if Frau Schwermuth hadn’t discovered it.

In the place where Poppo von Blankenburg spent a day flattering a windmill, bewitching it, whispering sweet nothings to it, until in the evening he heard a sigh – perhaps it was the mill, perhaps it was the wind – whereupon he found that he could grind such fine, pure flour that at the Anna Feast, which was soon celebrated, the villagers hardly touched any meat once they had tasted the bread; in that place a wind turbine stands today.

The fourth mill, the one on the postcard, was demolished by Belorussians in the last days of the war. It then occurred to them that flour wasn’t a bad idea, and they put the mill back in running order. The bread, which had a sour flavour, tasted wonderful to anyone who could get hold of any. We can still hear the grinding sound of the mill. We remember Alwin, the miller’s man here in the war. He had crooked teeth and could do conjuring tricks, he made the coins brought by servants coming to collect the flour disappear, and days later they found a coin in their bread, what a surprise! Alwin had to stop that game when matters of hygiene were taken seriously. After that he always guessed which card was the King of Hearts. The Belorussians shot him outside the mill. His name was Alwin, he had crooked teeth, and he could do conjuring tricks.

The mill itself had a name, but it got lost among the rubble.

It was demolished in 1960 and carried away, bit by bit, to our gardens, our walls, our cellars.

4. The Promenade: lined by ash trees as it still is today, so there’s not much change there. The lake on the left, the town wall on the right. A bench between them. Shady. Shade is the theme. A young woman and a young man are sitting on the bench, holding hands. She is in white, with a brooch on her collar, he is trying to follow the fashion for moustaches. The year is 1941. Hardly anyone wishes you “Good day” now. Either it’s “Heil Hitler” or you don’t give a greeting at all, but in a public place like the promenade no one would like to appear discourteous.

An ordinary sort of couple. Not too good-looking, not too elegant. Hands perhaps a centimetre or so apart. We say they are a couple because we know how it turned out; they almost held hands that day; there was a wedding, and nine months later along came Herrmann. Only they weren’t in love. Not on the promenade, not in the bad times that were coming and fired up many a relationship. They stayed together, yes, and they didn’t bother each other. You could say they behaved to one another all their lives like their hands on the postcard, just about to touch. If you look closely, you can see that the young woman on the promenade is suppressing a yawn.

An ordinary sort of couple. Not too good-looking, not too elegant. Hands perhaps a centimetre or so apart. We say they are a couple because we know how it turned out; they almost held hands that day; there was a wedding, and nine months later along came Herrmann. Only they weren’t in love. Not on the promenade, not in the bad times that were coming and fired up many a relationship. They stayed together, yes, and they didn’t bother each other. You could say they behaved to one another all their lives like their hands on the postcard, just about to touch. If you look closely, you can see that the young woman on the promenade is suppressing a yawn.

Two people under the ash trees on the promenade. Two people who wouldn’t have spent their lives together but for the promenade. If Herr Schliebenhöner hadn’t stopped them separately and asked them to pose for a photo on the bench, they’d have passed each other a little way up the promenade with a shy “Heil Hitler,” and that would have been it.

You would have been able to see the ferryman from the promenade. And the women in Frau Kranz’s first painting. Three bells are resting under the ash trees beside the lake. Perhaps they like it on the promenade.

That well-lit promenade. That subsidized, undermined promenade. Ah, those mice who scurry over the tarmac. A little refuge for those who may be in love, a forum for proletarians, a place for Anna to run when she goes running, a country road for satnav devices. That eternal promenade. Our promenade.

Extracted from Before the Feast. English translation © Anthea Bell

Saša Stanišić was born in 1978 in Yugoslavia (now Bosnia-Herzegovina), and moved to Germany with his family as a refugee from the Bosnian War aged fourteen. Before the Feast, his second novel, was a bestseller in Germany and won the prestigious Leipzig Book Fair Prize, and is now published by Pushkin Press, translated by Anthea Bell. His award-winning debut How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone has been translated into 30 languages, and is also published by Pushkin Press. Read more.

Saša Stanišić was born in 1978 in Yugoslavia (now Bosnia-Herzegovina), and moved to Germany with his family as a refugee from the Bosnian War aged fourteen. Before the Feast, his second novel, was a bestseller in Germany and won the prestigious Leipzig Book Fair Prize, and is now published by Pushkin Press, translated by Anthea Bell. His award-winning debut How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone has been translated into 30 languages, and is also published by Pushkin Press. Read more.

@sasa_s

Author portrait © Katya Sämann

Anthea Bell is a multiple award-winning translator from German, French and Danish, known for her translations of Stefan Zweig, W.G. Sebald, Hans Christian Andersen and the Asterix books among others. She also translated Saša Stanišić’s How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone, winner of the 2010 Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Prize.