Hardy perennials

by Christopher Nicholson

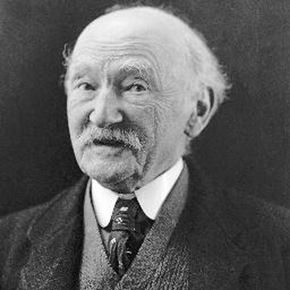

Portrait of Thomas Hardy by an unknown photographer, c. 1924

My novel Winter describes a domestic crisis in the life of Thomas Hardy. Hardy is among the greatest of English writers, famous not only for novels like Far From The Madding Crowd and Tess of the d’Urbervilles but also for many beautiful and haunting poems. He was a fascinating and complex man, full of paradoxes. He wrote poems that were highly personal and emotionally open, but in daily life he was intensely private and reticent. In my novel, set in the winter of 1924–25 at Max Gate, his home on the outskirts of Dorchester, the 84-year-old Hardy becomes preoccupied by a young and beautiful woman called Gertrude Bugler, who happens to be playing the lead role in a local amateur dramatisation of Tess. Hardy’s middle-aged wife, Florence, grows more and more anxious as the winter goes on. Here is my top ten Hardy works, interpretations and ephemera.

1. The Woodlanders

Of Hardy’s late, great novels, this is the one that I return to again and again. The Woodlanders (1887) has one of the most beautiful openings to any English novel, rather like the start of a fairy tale – one winter dusk, deep in the countryside, a solitary man is trying to find his way to a hamlet hidden in the woods….

2. The Undiscovered Country: Journeys Among the Dead by Carl Watkins

Hardy was fascinated by ghosts, so much so that he once said that he would cheerfully give up ten years of his life to see one. He would have loved Watkins’s unusual and very thoughtful book about the history of ghosts in Britain. Its real subject, and one it tackles with great erudition and eloquence, is the shifting nature of belief in the afterlife.

3. Thomas Hardy: A Biography Revisited by Michael Millgate

Several excellent biographies of Hardy have been published in recent years, but the best – or at least the one that helped me most when I was writing Winter – is Michael Millgate’s extensive 2004 revision of his classic 1982 work. Millgate has devoted his life to the study of Hardy, and it shows in the depth of his knowledge and the assurance of his prose.

4. Portrait by an unknown photographer

My favourite photograph of Hardy is one that appears in Claire Tomalin’s 2006 biography, Thomas Hardy – The Time-Torn Man (above), taken when he was 84 years old. Largely bald save for a little white hair and a moustache, smartly dressed in a white shirt and tie, a wool cardigan and a dark, tweedy jacket, what I love about this photo is that it catches him not in one of his melancholic or reflective moods, but as he is making some amusing remark. His mouth, slightly open, is on the point of breaking into a smile, and his eyes are twinkling. It’s a photograph that immediately makes one warm to him.

5. ‘Proud Songsters’

Hardy kept writing poetry deep into old age, and ‘Proud Songsters’ is the poem of his last years that I love most. An expression of his belief in the regenerative power of life, it’s a simple lyric imagining how the birds that one hears in full song – thrushes, finches, nightingales – were, just a year or two earlier

… only particles of grain

And earth, and air, and rain.

It appears in The Poetry of Birds, a fine anthology edited by Simon Armitage and Tim Dee (2009).

6. ‘The Water’ by Johnny Flynn featuring Laura Marling

When I was writing Winter, this is one of the songs that I kept playing (and that kept on playing in my head). It’s a beautifully flowing piece, slightly melancholic in tone, about a river spirit. The lyrics are mysterious and curiously powerful: ‘The water sustains me without even trying…’ It appears on Flynn’s 2010 album Been Listening.

7. Johnny Flynn’s Viola

7. Johnny Flynn’s Viola

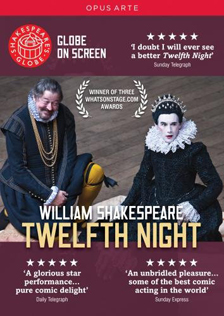

Johhny Flynn is also an actor, and he was marvellous as Viola in the all-male production of Twelfth Night performed in London in 2013. It was directed by Mark Rylance, who played the part of Olivia. I doubt I’ll ever see a better production of the play, which is now available on DVD. Shakespeare greatly influenced Hardy and, his yearning for Gertrude notwithstanding, would surely have enjoyed Flynn’s performance.

8. The Face of Battle by John Keegan

In May 1876, Hardy and his first wife Emma visited the battlefield at Waterloo. Emma was exhausted by the trip, but Hardy had always been fascinated by the subject of Waterloo and would come back to it thirty years later in his verse drama The Dynasts. The best account of the battle that I’ve ever read – one that concentrates on the experiences of the men in the thick of the fighting – is John Keegan’s from 1976. In addition to Waterloo, it also studies the battles of Agincourt and the Somme.

9. After London, or Wild England by Richard Jeffries

Among the books in Hardy’s library at Max Gate, his house near Dorchester in Dorset, was a 1905 pocket edition of the works of Richard Jefferies. Jefferies is in the first rank of English nature writers, and this short novel from 1885 is of his least known but most powerful productions. Way ahead of its time, it’s a post-apocalyptic tale of England sinking back into medieval chaos, with London submerged beneath a black, toxic lake.

10. A History of the Countryside by Oliver Rackham

If Hardy were alive today, one of the books on his shelves would undoubtedly be Rackham’s supreme 1986 account of why things are as just they are in the English countryside.

Christopher Nicholson’s earlier books are The Fattest Man in America and The Elephant Keeper, which was shortlisted for the Costa Novel Award and the Encore Award. Winter is published by Fourth Estate. Read an extract.

christophernicholsonwriter.com