History from the wings

by Mika Provata-CarloneIn times of crisis, sociohistorical impasses, and what the French scholar John Cruickshank has termed, on a different occasion, the despair in the face of “man’s metaphysical dereliction in the world”, the individual and collective instinct is to turn to parallels, contrasts, and to recent or very distant memory. To familiar or unfamiliar territory. We seek the common or even the most uncommon denominator in order to create comparative paradigms, contexts of reference, and patterns of interpretation and understanding. The pursuit can be scholarly or fatalistic; a strategy of insight or of evasion; a fearless confrontation with possibilities, probabilities, forecasts, and hard (often harsh and unpalatable) facts, or, again, a demagogical exercise of placation, mollification, poll-casts and moral escapism.

For a few years now it has felt that the world is being held suspended in a constant state of tension and turmoil, placed on the most dire and critical, the most unyielding scales of historical judgement on every level, from social conditions to economics, from spiritual and cultural prospects to techno-material ambitions, from environmental policies to politics head-on. Our private and communal response has been to trace clear or tenuous lines of meaningfulness or absurdity through events, signs and omens, so as to derive some narrative of redeemed structures, retrieve a centre presumed lost, envision an overarching order of sense and purpose we can espouse or even valiantly (yet concretely) resist.

The predominant exemplum that seems to appear time and time again is the period of the 1930s and its WWII aftermath, for it simply has it all: the sense of existential and spiritual crisis; the stark socioeconomic quandaries; the vicious racial, ethnic, social and gender ideologies; the veneration of science and material industry, not infrequently at the expense of humanity and the Humanities. It has villains and heroes aplenty, stories from above and histories from below; it boasts treason, evil both banal and hellish, staggering self-sacrifice, and heart-rending commitment to a humankind on the brink of self-extinction. The focus, when any parallel courses are mulled over and perused, tends to be mostly on the bold headlines: populism; propaganda; power struggles; Panglossian or Machiavellian politics; democracy vs. totalitarianism; vox populi vs. the wills and ways of governments or of murkier governing forces; the sense of uncertainty, the spirit of solidarity, the unique valour of resilience, kindness and empathy.

Questions are asked: what is different and how are we similar still, perhaps, for all the lessons of history, or thanks to them? Are we the same people, or is there a Hesiodic paradigm as well at work, with human ages marking the transitions from ideal to decadent or from gold to gilded? Vico-echoes too enter into play, the cyclicity and very human dimension of historical time, which creates immutable behavioural models, so beloved of today’s data scientists. Defining such an anthropocentric, essentially Protagorean view of eternity, where man feels indeed the measure of all things, Vico claims that “Men first feel necessity, then look for utility, next attend to comfort, still later amuse themselves with pleasure, thence grow dissolute in luxury, and finally go mad and waste their substance.”

Looking afresh at Astrid Lindgren’s wartime diaries offers an extraordinary testimony to the normalisation of our folly, to the remarkable ways in which our vision of things contorts in the most improbably spectacular manner.”

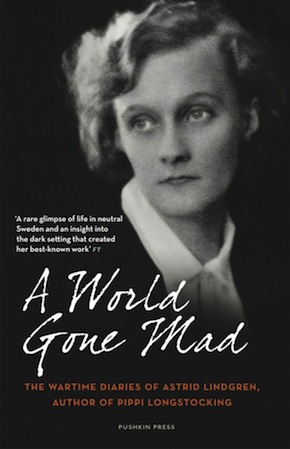

In seeking to find the historical parable or causal parallel that will point the way to clarity and coherence, to a semantic way out of the irrationality of our predicament, we sometimes skip the necessary step of observing critically and with scholarly detachment the madness itself, its often quiet, uncanny absurdity, its shocking array of lesser yet overwhelming symptoms of darkness, incriminatory lapses, and prior or ongoing fallacies. Looking afresh at Astrid Lindgren’s wartime diaries, published in Sweden for the first time in 2015, and in English only a year later by Pushkin Press, offers an extraordinary testimony to the normalisation of our folly, to the remarkable ways in which our vision of things, the presumably straight lines of our light of reason, are flexed and bended, contorted in the most improbably spectacular manner. A World Gone Mad is a highly unusual, complex document, a multicoloured bird of paradise within the genre of war diaries or memoirs: it is a stark and startling journal intime of inertia rather than of life through tragedy and in tumult, a meticulous, though erratic and idiosyncratic archive of public information and disinformation in the form of press clippings and commentary, a logbook tracing the development of a female authorial conscience and voice, and a historical testament of a crisis seen from an almost hallucination-inducing without. If read with the gamut of sentiments evoked by the current pandemic (among other things) in mind, it will send a shock to the system, as well as provoke a powerful, exceptionally fruitful sense of incredulity, and necessary questioning.

A World Gone Mad almost screams for contextualisation. Published at the heart of new debates regarding the legitimacy and viability, the ethics and historical practice of neutrality or non-involvement during WWII (or under any circumstances), it stands defiant and revealing, profoundly human and fragile, while being at the same time often troubling and unsettling. It purports to give the ‘view from afar’ or from the wings, the panoramic contemplation from a place where meditation and contemplation still appear possible; it claims to present the impartial, objective point of observation from where to record the darkening horizon and the emerging tableau of blackness. It is a place several times removed from the hell it describes and tries to account for, a place where the newspaper photos of disaster and the broadcasts of doom are poignantly interspersed with blossoming fields, running streams and the chirpings of birds, and where frontlines and carnage are blurred with the outlines of new house interiors, children’s growing pains, and the rather Lucullan menus under Swedish rationing.

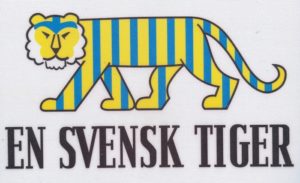

1941 propaganda poster by Bertil Anqvist for Sweden’s ministry of information. The tagline ‘A Swedish tiger’ also translates as “A Swede stays silent’

In her foreword, Lindgren’s daughter, Karin Nyman, writes of Sweden at war that “It felt special, but in some strange way reasonable and justified, for us to be the ones who were spared”, to have received a special dispensation from fate or history – a statement that supplements, rather than contrasts, Lindgren’s own comment that Sweden’s state of normality felt like “a pure, underserved, unparalleled state of grace.” Sweden opted for a particularly thorny form of neutrality during WWII, which it upheld staunchly, if not always convincingly, audaciously going it alone even in the face of public outcry. It chose non-participation (with variations on the theme) as the world around it was under the total lockdown of war. There have been critics of such a non-position from the start. Winston Churchill, that popular historical avatar of our times, blasted Sweden during the war for turning a blind eye to moral questions, placing economic and national security over the duty to a broader humanity and life. In 2019, on the occasion of Carl Svensson’s documentary En Svensk Tiger: The Swedish Silence, David Stavrou wrote in Haaretz of “the skeletons in Sweden’s closet”, and in 1997, Roger Cohen wrote a scathing piece in The New York Times about ‘The (Not So) Neutrals of World War II’ where he quoted Arne Ruth, a Swedish journalist: “Sweden was not neutral; Sweden was weak.” The conclusion of Cohen’s analysis is perhaps the gadfly of all times, then as much as now: “A basic [shocking] question: And what did you do?” In Lindgren’s case, she simply wrote a diary that said it all.

Replace Hitler/War with Coronavirus and it becomes a snapshot of the incredulity, initial inertia and horrendously tragic uncertainty of the new predicament, of the easy slide from crisis to normality.”

The first entry of Lindgren’s diary requires unnervingly little change for it to sound as though it had been written under our own circumstances. Replace Hitler/War with Coronavirus (an exercise undertaken daily in the world media) and it becomes a snapshot of the incredulity, initial inertia and horrendously tragic uncertainty of the new predicament, of the easy slide from crisis to normality: “Oh! War broke out today. Nobody could believe it.” Only yesterday, she says, “we sat there giving Hitler a nice, easy telling-off and agreed there was definitely not going to be a war.” Familiar scenes follow: “I have managed to restrain myself from any hoarding until now, but today I laid in a little cocoa, a little tea, a small amount of soap and a few other things.” Eventually she will lay in a little butter, sugar, and no less than 20kg of preserved eggs, as well as having a running supply of smorgasbord necessities and Nordic feast staples… There is unwitting comedy in her earnest transcription of quotidian details and the fastidious registering of provision for adults and children alike, from clothes and food, to Christmas and birthday presents, plain or sumptuous meals, and escapes to the countryside. Alongside it, there is the concentrated effort to penetrate “the fall of the white race and of civilisation”, the actions or inactions of people and governments, the meting out of blame, responsibility, guilt. There are glimpses of both pathos and bathos, as in the tragic events of the battle for Finland, and the cameos of how news are reported through a harrowing blend of darkness and light: “they say the French put up placards on the Western front: ‘we won’t shoot.’ And that the Germans replied on their placards: ‘nor will we!’ But it can’t be true”; or the entry dedicated to Sweden’s victory in the military patrol race at the Nordic World Ski Championships in 1941, “beating Germany and Italy and Switzerland and Finland. It is splendid being able to show the Germans what sort of soldiers we have in this country.” Readers will perhaps experience a reeling sensation at such parallel universes… Lindgren, like much of her world, like many before and after her, vacillates constantly between neutrality and action, critical apperception and the exercise of convincing oneself that the nonsensical makes perfect sense, because it has to, in order for one to be able to overlook the chaos (but perhaps not see beyond it).

The perspective of A World Gone Mad will seem jarring when contrasted to WWII accounts from just about everywhere else: it is highly localised, a chink in the wall rather than a macroscopic vision. For some readers the tilted angle will cause vertigo, a sense of disorientation, and it will certainly raise many questions about the definition of right action, the conditions and preconditions for peace, the ethics of impartiality from within the context of partial or sufficient neutrality (Germany will use “insufficient neutrality” as the casus belli against Norway, Belgium, Holland). The constant, disturbing adage is what could be done so that it may be someone else’s fate at stake. Sweden is not the exclusive focus of scrutiny in this sense. The politics of strategic calibration of power and of loss, of outright forfeiting the fate of nations, which were followed by the Allies and the Axis powers alike, are also a substantial area of inquiry, and Lindgren evinces a particularly heightened sensitivity regarding texts and subtexts, the nuances of rhetoric and the layers of meaning in official language, political propaganda, national mythography and private statements and thoughts: “The Western powers don’t want peace between Russia and Finland at all. They like the idea of Russia being kept busy so it can’t deliver anything to Germany,” she notes on 12 March 1940.

Through her effort to understand facts and motives, events and circumstances, convictions and subterfuges, good and evil, right and wrong, agency and destiny, Lindgren begins the historical dialectics that would culminate after her death in a reappraisal of individual and state responsibility and response to moral and material crises. And she embodies uniquely the frequent human dilemma between self-questioning and self-justification, at every level. Lindgren had both the citizen’s view and the more privileged, morally loaded perspective of someone with access to classified information. Her work for the Swedish Intelligence Agency as mail inspector afforded her a more dire and stark insight into the reality of war in Europe and across the world than the sanitised or polarised versions in the press, and the struggle to negotiate factual truth and satisfactory interpretations of it is palpable throughout, together with the tension between what emerges as a very strong personal voice and a voice for Sweden in the present and for the future.

One is struck by the determined humanity of her diary entries but also by their detachment towards everything that is not what she terms Nordic. A peculiarly skewed perspective of geopolitics and history beyond that sphere makes for extraordinary pronouncements, many of which are startlingly revelatory. Others are bemusingly condescending or borderline arrogant. Lindgren’s positions on Britain, Italy, France, Russia, will provide much food for thought, while her conditional condemnation of Germany will perplex or even shock at times. This is an extraordinary alternative eye-witness report of WWII, which focuses not on active events, on the explosive surge of battles and the kaleidoscopic emergence of war fronts, but on the webs and patterns left on an invisible screen far beyond the action: the schemata and archetypes of human error and aggression, the will to dominate, the drive for self-preservation and delusion, and, in rare glimpses, the frailty and precariousness of life. It offers an opportunity to examine human consciousness at the crossroads of moral and historical conscience, to analyse the narrative of interpretation, justification or selective perception that is formed and becomes embedded as truth in this particular historical case – but not only.

One cannot accuse Lindgren of a static perspective – and this is one of the most absorbing and revealing elements in her diaries, when initial, often discriminatory comments are allowed to develop into more mature insights and appreciations as events unfold and her personal attachment to stories of individuals or nations is given space to grow. Greece is a case in point: from its qualification as “Little Greece”, to be ridiculed or condescended to at best, it seems to have struck Lindgren (with Belgium and France as close seconds) as representative of the war’s devastating tragedy outside the Nordic bloc, and it is remarkable to see what selection of news made it through to the Swedish press at the time, and hence into Lindgren’s diary. There are details concerning the situation and conditions in countries under German occupation that show extraordinary microfocus and detailed access to evidence (including Nazi concentration camps), as well as an interest in non-linear, atypical historical accounts. The resulting ensemble is both short-sighted and vastly comprehensive, even when facts are plied and stretched, when ingrained biases are at stake. A World Gone Mad in this sense is a very sensitive register of volatile emotions, inculcated preconceptions, a virtual thermometer of tensions and releases on an individual but also global level.

Lindgren’s own experience and her evaluation of historical experiences might be particularly useful as a chamber of mirrors to guide us to true reflections of ourselves, to a better clarity of vision and insight.”

In retrospect, this is the diary of a very public figure, a writer who marked generations of readers in ways few have, a woman who forged a very powerful model of what children and women could do and be. From a synchronic perspective, A World Gone Mad is also, at times and in a certain sense, the notebook of the common man or woman. This is evinced in its staggeringly clashing collages of history and private life and thoughts, the record it leaves of Swedish society at large and in its minute self-obsessed details, but more especially in the rhetorical tour de force that Lindgren achieves in her concluding entries: on the day of Germany’s surrender, she writes that Sweden has reasons to be proud, “What would the world look like now if we’d been swayed by [its] disappointment [at Sweden’s neutrality]! Germany and Russia united, dear oh dear, then Britain would have been in a real fix… Somebody’s got to stay neutral, otherwise there can never be peace – for want of intermediaries.” It is a revisionist declaration that will ring reverberantly to sensitive ears.

As we consider, perhaps, more recent events, personal, national and international choices, responses and responsibilities, actions and inactions, truths and variant interpretations, reasons and hidden motives, Lindgren’s own experience and her evaluation of historical experiences, even her anxiety to justify, might be particularly useful as a chamber of mirrors which might guide us to true reflections of ourselves, to a better clarity of vision and insight. Part of that process will require determining magnitude and insignificance, understanding when to uphold views, positions and convictions, and when to abandon and surrender in order to be humble and sincere. Lindgren’s later works, the cursus of her life, show that similar thoughts perhaps went through her own mind at a certain point in time, giving rise to an extraordinary legacy of human observation and very human understanding and analysis. Her war diaries are records of false steps and real yearnings, of true limitations and human fragility, of unmitigated darkness, both within and without, of a state of mind in a “world gone mad”. They are also, perhaps, a guide beyond their own possibilities, as they expose us to ourselves, to our self-deception and deceptions, to our strengths, limits and feet of clay, at yet another critical point and crossroads of human time.

Astrid Lindgren (1907–2002) became famous almost overnight after publication of her first Pippi Longstocking book in 1945. She received numerous honours including the Hans Christian Andersen Award and the Gold Medal of the Swedish Academy, and her books have sold 160 million copies worldwide. A World Gone Mad, translated by Sarah Death, is published by Pushkin Press.

Astrid Lindgren (1907–2002) became famous almost overnight after publication of her first Pippi Longstocking book in 1945. She received numerous honours including the Hans Christian Andersen Award and the Gold Medal of the Swedish Academy, and her books have sold 160 million copies worldwide. A World Gone Mad, translated by Sarah Death, is published by Pushkin Press.

Read more

@PushkinPress

Sarah Death is a prize-winning literary translator, mainly from Swedish, with over forty translated titles to her name. She has translated works by Lena Andersson, Kerstin Ekman, Sven Lindqvist and Steve Sem-Sandberg, as well as Tove Jansson’s Letters From Tove (Sort of Books, 2019). The former editor of Swedish Book Review (2003–15), in 2014 she received the Royal Order of the Polar Star for services to Swedish literature.

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.