Horses

by Mareike KrügelHelli is sitting in the middle of the forest path watching me approach. Aladdin is a few metres further on, drenched in sweat, his flanks quivering. My horse slows of her own accord, allowing me to focus and regain control over myself, the reins, the situation. As soon as Scheherazade has dropped back to a walk, I slip out of the saddle and rush to Helli. She’s crying softly, quite unlike her usual self.

“Are you hurt?” I ask breathlessly.

“Don’t think so. Not much,” she says. She shows me a few scrapes on her arms and hands. There’s a graze on her face too and leaf mould on her jacket.

I’m hot – my cheeks are burning. Here among the trees there’s no cold wind and the ground is muddy, not frozen. The horses amble over to us. Aladdin sniffs Helli’s hood and sprays a small shower of horse snot down her neck. She looks up at him, strokes him between the nostrils and murmurs: “‘It’s all right. Wasn’t your fault.”

I’ve never seen her like this. Both the soft, distraught weeping and the implicit admission of guilt are completely out of character. She usually wails like a fire-engine, throwing her head back and opening her mouth so wide that you can see her molars, and it’s often hard to tell whether she’s angry or sad. She sometimes curls up on the floor, or even tears her hair or punches the wall. She can’t calm down on her own – I have to wrap her in my arms and hold her tight until she stops squirming and goes all limp. She ends up conked out over my shoulder or on my lap, giving the occasional hiccup as the sobbing gradually subsides.

If she’s angry or gets into trouble, it is, of course, always someone else’s fault. Often it’s objects that rebel or get in her way or play up, and sometimes it’s fate that’s unkind to her, but most of the time I’m the one to blame for her tantrums. I give her the wrong glass, fill it with the wrong drink, distract her so that she doesn’t watch out and runs into the open door, give her reproachful looks to make her feel guilty about some incident in the school cafeteria that I can’t possibly know about, nag her to do her homework, brush her hair or thank Grandad for a Christmas present, or freak out her friends with embarrassing small talk, asking them how old they are or what they’re called or where they live. In the end, what it comes down to is that she needn’t have got angry at all, if only I’d been able to read her mind.

***

The horses are steaming – I can smell their coats and the trees and a whiff of the waterproofing on Helli’s jacket. For a moment I can’t remember how I got here. The winter woods are very quiet. I try to put an arm around Helli but she pushes me away. It’s a gentle push, not a shove, and the forlorn, lonely feeling leaves me, just for a moment.

“Mum,” she says, and there’s something in the way she says it that makes my heart swell. Alex doesn’t need me anymore, not really, but Helli’s still my little girl, at least for now. Sometimes I wish she’d stay my little girl forever, so I could always take care of her.

“Yes?”

“Can I get that medicine?”

For a moment, I don’t know what she’s talking about. I rummage frantically through my brain trying to figure out what she’s talking about. Medicine?

“You mean painkillers? Does anything hurt? Move your legs,” I say.

I feel the warmth of the horses and hear them cropping the grass. I’d like to stay here with Helli and never return to civilisation. Here I could be me and Helli could be Helli. There are no medicines here, no chemo.”

She moves her legs, watching them intently. At the edge of the path, Aladdin and Scheherazade begin to crop stray blades of grass left over from summer. Greenish froth gathers on their lips.

“No, they’re all right,” says Helli.

“Tummy ache?” I ask, suddenly remembering what torture riding lessons were for me when I had my period. Jolting along on a trotting horse was agony, and as soon as the lesson was over I had to make a dash for the toilets before the blood started to run down my legs. The already shapeless sanitary pad in my pants was a bloody, twisted sausage by the time I got out of the saddle.

“Why?” asks Helli.

“You wanted medicine.”

“Oh, yeah. I meant the one the woman talked about where I do the tests.”

“Why are you asking about that now?”

Tears gush out of Helli’s eyes. “I don’t know what happened just now.” She starts to sob again. “All I remember is that I was really angry with Cindi for talking such shit and the next thing I know I’m in the woods, falling off some stupid horse. I’m always in trouble at school too and I don’t know why. What am I doing wrong? What should I do differently? What should I be like?”

“You should just be Helli,” I say. But that makes her cry even more. She’s so choked up now she can hardly speak.

“I don’t want to be Helli anymore. Being Helli is shit!”

“And you think taking the medicine might help?”

“No idea. But if it’d make my head shut up for once, I’d be happy.”

I take a deep breath. Even here among the trees, the chill of the frost is palpable – a freshness, as if the air were particularly rich in oxygen. I feel the warmth of the horses and hear them cropping the grass. I’d like to stay here with Helli and never return to civilisation. Here I could be me and Helli could be Helli. There are no medicines here, no chemo.

Helli says: “The medicine makes you thin too.”

“Where on earth did you get that?” I ask, but I already know the answer: even a child can find anorexics and bulimics exchanging weight-loss tips on the internet.

***

When we come out of the woods, leading the horses by their reins, the riding teacher hurries up to us. Heike is about my age, and sturdy, with short hair and a carrying voice. When it gets cold she sits in the riding ring with a cat on her lap to keep her warm during the lesson. She’s never sick, never loses her voice, never gets annoyed – but she’s never friendly either. The girls worship her.

“There you are,” she calls out to us. “Everything all right?”

I wave and nod vigorously so that she can see even from a distance. To Helli I say: “Do you still want to ride or do you need some time to catch your breath?”

“Ride,” she says. But when we get to Heike and she takes Scheherazade, Helli changes her mind. She lets go of Aladdin and throws herself into my arms, burying her face in my shoulder. She’s nearly as tall as me now – it won’t be long before I’m looking up at her. Maybe in some strange way it’s a blessing if you die before your children are taller than you. That way Helli would be my little girl forever – she’d remember me as someone she could turn to for comfort, a shoulder to cry on.

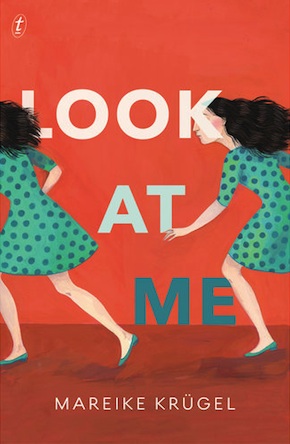

From Look at Me (Text Publishing, £10.99)

Author portrait © Peter von Felbert

Mareike Krügel lives in Schleswig-Holstein with her husband and their two children. She has received numerous literary awards, including the Friedrich Hebbel Prize. Look at Me is her fourth novel, and the first to be translated into English. It is out now in paperback from Text Publishing, translated by Imogen Taylor.

Read more

mareikekruegel.de

Imogen Taylor is a literary translator based in Berlin. Her translations include The Truth and Other Lies by Sascha Arango, Fear and Twins by Dirk Kurbjuweit and The Trap and The Stranger by Melanie Raabe.