Icons and believers

by Ayfer Tunç

“A terrific satirical take on the tackiness of modern Turkey… very lively and entertaining.” John Hodgson

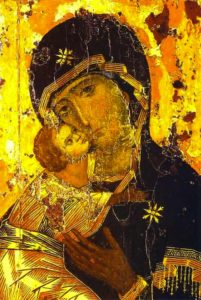

One day, during a thorough spring clean, Henna Meryem came across the long-forgotten icon. She became emotional, remembering her mum, who’d long since returned to dust, and had a bit of a cry and everything… But was there any reason to hang on to this Christian image? No. Yet it was too beautiful to chuck out. So she sold it to the rag-and-bone man Zülfü, who regularly passed down the street towards noon and gathered up whatever he could, scrap or still serviceable: broken TV sets, water heaters, old newspapers and copper wire.

Zülfü drove a hard bargain. He offered Meryem a melamine dining set for six, a wooden board brush, two washbowls, and, when she still wasn’t convinced, even threw in thirty-six wooden clothes pegs; but once she dug her heels in I want money! he was left with no choice. The money she wrung out of him went to pay the first instalment on a steam iron for her granddaughter, still in primary school. It never occurred to her that by the time this granddaughter was old enough to get married, far more advanced models would be available.

This was around the time of the dissolution of the Soviet Union when the border crossing at Sarp was opened and passenger liners started criss-crossing the Black Sea. Russians flocked to every city in Turkey; the town in which the Mental Health Hospital stood, with its back to the sea, was no exception. The new visitors set up stands at the port to sell the stuff they’d brought: splinter-rich Russian cigarettes, tinned caviar well past the use-by date, bottles of vodka with labels worn out from all that schlepping, eau de cologne whose alcohol had long since evaporated, Matrushka dolls, stale chocolate tasting of margarine, Red Army caps, fur kalpaks, drill bits, military binoculars, Phillips-head screwdrivers, pincers and Zenit cameras (a.k.a. the Kalashnikov of cameras) along with an assortment of lenses.

History had been rent open, and a medal once worn with pride and honour on one side of the world during the Cold War was now worth less than a plate of fried cheese and a panful of anchovies in a neighbouring land.”

As the stands sprawled out and a previously quiet section of the port mushroomed into an open market of sorts, Zülfü grabbed one for himself. The icon was placed on a purple velvet spread, next to Russian teapots, pans, enamelled buckets, old fountain pens, small boxes of indeterminate purpose and censers.

Our Lady of Vladimir, the holy protectress of Russia, 12th century. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow / Wikimedia Commons

Journalist Berrak Armağan, who loathed her editors for insisting that she leave the Journalists’ Union, an organisation on the brink of obsolescence and thus entering a vegetative state, was here to file a somewhat belated report on the unstoppable flow of former Soviet citizens, commonly referred to as Russians, who’d left an astoundingly vast land and crossed a sea they knew well to a shore they knew not at all – the dismal detritus of an empire manning temporary stalls, their faces brightening briefly as they chatted in their own tongue before clamming up again, a people who looked proud and doomed at the same time. But instead of talking to these people to probe the economic and social reasons that had driven them to this shore, she mooched around the open market all day long and shopped.

From these sad, tense vendors, who had sailed mostly from Black Sea towns like Sochi, Batumi and Odessa, in a few months picking up just enough Turkish to get by, she bought the following: eight hammer-and-sickle CCCP badges, one bronze medal of honour she was certain had been bestowed upon one of the Red Army’s glorious soldiers, a shedload of Red Square, Kremlin, Lenin and Stalin postcards, a double long-playing album titled Troika, consisting of folk music from countries that had made up the former USSR (such as Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Armenia), and another LP, this one a late sixties recording of the Baku State Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by the famous Rostropovich before his fall from grace and the subsequent stripping of his citizenship for associating with the dissident writer Solzhenitsyn.

The total had come to less than the price of lunch in a nondescript tradesmen’s restaurant nearby. The records were worn, the badges tarnished and the medal was nestled in a dusty box – and thousands more badges and dozens of medals still languished on those stalls. She would never know the hands that had revered these decorations, the chests they’d been pinned upon, or the hopes they had raised, these articles crushed by the most painful devaluation of all. Something had happened in the fabric of time, something had thundered out of the blue, history had been rent open, and a medal once worn with pride and honour on one side of the world during the Cold War was now worth less than a plate of fried cheese and a panful of anchovies in a neighbouring land.

That’s enough melancholy for now, she thought, on the verge of leaving, her gaze caressing each and every article, until she noticed The Virgin Mary Holding the Infant Jesus on Zülfü’s stand.

Since Meryem had proved to be such a tough haggler, the rag-and-bone man now had no intention of accepting anything less than his stated amount. But the icon had been lying there for days without attracting a single glance; he realised that flogging an icon in a Muslim city was like trying to sell bacon there. Another buyer might take months to appear, he reasoned, and since the Istanbul journalist showed an interest… So he agreed to a quarter of his asking price and got rid of the icon, which had been taking up space anyway.

It was the time of Excuse mes, of We were wrongs for Turks, who, for decades had been inculcated in the virtues of self-sufficiency and prudence, of donning batik dresses and Bodrum sandals and sitting on pine furniture. The press was no longer the Fourth Estate, foreign investment was incentivised, and businesses with wild growth rate targets tempted journalists with generous junkets – the same journalists who were aching to bury their venerated principles in order to keep up with the times – and a new generation of lifestyle magazine editors flooded the offices: young, leggy and beauty-obsessed.

Refusing to compromise her principles, Berrak eschewed these junkets and maintained her membership of the Union. At first, her editors tried to reward this ethical journalist. They sent her to Vienna to cover a conference of European social democrats. They also intimated subtly – too circumspect to say it out loud – that were she to leave the Union upon her return, promotion would follow – Wherever Europe’s social democrats were, Berrak would be there too! – and she would travel around the globe as an esteemed reporter. But all their hints went over her naïve head. She would only twig once she’d been moved from foreign news to one feature after another.

Ferhat came back to explain that his objection to the nude self-portrait was based on his concern for any relatives who might visit. On the other hand, his view about atheists hanging icons on their walls remained unchanged.”

After spending three days and nights with the European social democrats and filing detailed reports, Berrak set the fourth day aside for herself; after a few hours of discovering Vienna, a city big in stature but small in scale, she visited the Leopold Museum. As she was leaving, she shelled out for a beautiful Egon Schiele reproduction. She hung his nude Self-Portrait next to Guram Chaliashvili’s devotional icon The Virgin Mary Holding the Infant Jesus in her living room crammed with pine furniture, cacti and knick-knacks of myriad types.

Schiele had depicted his own genitals in graphic detail, truncated his legs at the ankles, covered his face with an arm and painted the single visible eye red. The tremendous conflict between the intense sorrow that emanated from this emaciated body expressed in sharp, harsh lines and the holy mother holding God’s plump son on her lap created a bizarre tension on Berrak’s wall.

This tension weighed inordinately on her live-in boyfriend and fellow journalist, Ferhat. He objected to both works. Utterly devoid of any interest in religion or piety, his question What’s this arse-licking to Christians about anyway? ignited a massive row whose topic soon moved away from the icon. He then trained his fury on the Schiele, exclaiming, Call this art? You can see his bollocks an’ all!, and stormed out.

They soon made up. Ferhat came back to explain that his objection to the nude self-portrait was based on his concern for any relatives who might visit. On the other hand, his view about atheists hanging icons on their walls remained unchanged: this was nothing less than an affectation.

In the end they came to an agreement, or rather, Ferhat won. The Schiele was removed and placed in a drawer, and the Virgin Mary was demoted to staring sadly from a corner of Berrak’s desk instead of her earlier pride of place in the living room.

From The Highly Unreliable Account of the History of a Madhouse, translated by Feyza Howell (Istros Books, £11.99)

Ayfer Tunç is one of the most respected and widely read authors in Turkish literature. She broke onto the literary scene with her short story collection The Yore Hotel, which was highly praised by both the literary circles and readers. She started working as a journalist in 1989 and then as Editor-in-Chief at Yapı Kredi Publishing House from 1999 to 2004. Apart from novels, she has written many screenplays. In 2003 she won the international Balkanika Literary Award with her book My Parents Will Visit You If You Don’t Mind: Our Life. The same year her screenplay Cloud in the Sky, inspired by Sait Faik’s short stories, was filmed and televised. The book was translated into six Balkan languages, along with the collection The Aziz Bey Incident (Istros Books, 2013). The novels The Night of the Green Fairy and The Highly Unreliable Account of the History of a Madhouse remain her bestsellers. She has also co-authored a non-fiction study named Two Faced Sexuality with Oya Ayman. The Highly Unreliable Account of the History of a Madhouse is published in English for the first time by Istros Books.

Ayfer Tunç is one of the most respected and widely read authors in Turkish literature. She broke onto the literary scene with her short story collection The Yore Hotel, which was highly praised by both the literary circles and readers. She started working as a journalist in 1989 and then as Editor-in-Chief at Yapı Kredi Publishing House from 1999 to 2004. Apart from novels, she has written many screenplays. In 2003 she won the international Balkanika Literary Award with her book My Parents Will Visit You If You Don’t Mind: Our Life. The same year her screenplay Cloud in the Sky, inspired by Sait Faik’s short stories, was filmed and televised. The book was translated into six Balkan languages, along with the collection The Aziz Bey Incident (Istros Books, 2013). The novels The Night of the Green Fairy and The Highly Unreliable Account of the History of a Madhouse remain her bestsellers. She has also co-authored a non-fiction study named Two Faced Sexuality with Oya Ayman. The Highly Unreliable Account of the History of a Madhouse is published in English for the first time by Istros Books.

Read more

@Istros_books

Feyza Howell is a graphic designer, producer, businesswoman and translator. Her other translations include Madam Atatürk by İpek Çalışlar, The Concubine and Unto the Tulip Gardens: My Shadow by Gül İrepoğlu, Kurt Seyt & Shura by Nermin Bezmen, and The Book of Madness by Levent Şenyürek. The Highly Unreliable Account of the History of a Madhouse is her favourite book of all time.