Immortality

by Nicholas Royle

“A curiously compelling investigation of the nature of writing and the writing of nature.” Robert Macfarlane

The sentence he was writing as he hovered over his keyboard, staring at the screen, pursuing the pulsing vertical of the cursor as it left in its wake a new letter, then word, punctuation, space, till the final full-stop, gave Stephen Osmer such an access of pleasure that he died. He skipped off his seat like the carriage on an old typewriter at the end of a line and there he was, tarrying with a convulsion then completely still, on the floor.

He was doing what he had been every day for the past ten days or more, taking to heart the advice of T.S. Eliot: write in the calm of the early dawn. This counsel, given in the privacy of a letter to Lawrence Durrell but set forth with that canny aplomb suited to statements applicable to any would-be writer any time in history, he had long made fun of, keen as he was on cycling and galvanised in the realm of pre-breakfast activities rather by his own twist on the phrase: ride in the calm of the early dawn. Ride or run: for years he had been out, come rain or shine, tracking the empty streets or pavements of London through that eerie period of the morning when, in Wordsworth’s phrase (still oddly apt), the very houses seem asleep.

But for the past couple of weeks he had followed a quite new course. He worked relentlessly through the quietness that suspends central London before the first rumbling of buses, the yawning and electronic voices of delivery vehicles, the interring whoosh of traffic. It was mid-July and the dawn chorus of sparrows had been going on for some minutes. Set up at a little mahogany desk by the window, in his beloved little mews bedsit off Doughty Street, he had wrangled with himself at inordinate length, slowly drinking his first coffee of the day, over the closing section, the final movement as he thought of it, with which he had been preoccupied since Thursday, and then everything gave way. He was reaching for the words, or the words were reaching for him, embarked on the sentence, come upon by an elation unlike anything he had ever felt, a paper ecstasy clanging out of iron agony, his being in flight at the machine, as if silent, the words dropping into place, his eyes flickering between keyboard and screen, then finished.

***

The funeral was well-attended, despite being out of town. Ben and Jane Osmer had moved to the Cotswolds after Ben took early retirement. She stayed at the cottage, where she had been since hearing the news, like a frozen stalk. Such was the onset of grief, an Ice Age in an instant. No one plans for the death of their children. Ben was a Jew and lapsed communist, Jane the agnostic but devoted daughter of a Church of England vicar. A cremation in Cheltenham was all that could be envisaged. But quite a crowd came down from London, colleagues, admirers and loved ones, friends and relations. Even emerging from the surreal red velvet and brass shadow-show of the ceremony into the blinking light and drizzle, the song of thrushes and blackbirds, the plundering of worms and the green, faintly twinkling, still-dewy expanse of the cemetery was claustrophobic.

The editor of the Gazette herself said a few words. She highlighted the tragedy of dying at the age of twenty-seven, what a brilliant young man Stevie had been, what an exceptional future blasted.”

Ben made a speech that was even shorter than he had intended. He broke up after less than a minute, like a voice on a phone passing into a tunnel. Passionate about politics at university, his own career beginning at the Morning Star, moving on to promising positions at a couple of the broadsheets, Ben Osmer had had such hopes for his son. He could not say. For his son, he could not say, he – the boy had done well, the boy was going to do – and his daughter Sarah had to stand up and put her arm around him and help him back to his seat. Old colleagues of Ben looked on, pop-eyed in dismay, struggling to smile in solidarity. There was some muffled embarrassed snickering from a couple of Stephen’s fellow workers.

Then Sarah made a short speech, wishing to remember her brother for an inner stillness and purposiveness she would always find inspiring, for his kindness and warmth, for his loving protectiveness. She spoke of how on holiday as children, swimming at Welcombe Bay in north Devon, a sudden cold undercurrent had pulled her feet from under her and was dragging her out and Stephen had realised what was happening and, instead of shouting for help to their parents or others on the beach, swum after her and brought her back. That was what her brother was like.

The editor of the Gazette herself said a few words. She highlighted the tragedy of dying at the age of twenty-seven, what a brilliant young man Stevie had been, what an exceptional future blasted. Another colleague, Brian, hazarded a lighter tone, wanting people to remember how funny Osmer could be. He recounted a couple of cycling anecdotes. There was the time they were walking in Covent Garden, Stephen pushing his bike, in the company of Brian and another friend, both on foot, when Stevie spotted the Guardian journalist the late Simon Hoggart, one of London’s more notorious dislikers of people on bicycles. And Stevie straight away said watch this, mounted his bike and shot out of view, reappearing a minute later round the corner of Catherine Street, deliberately almost colliding with Hoggart, swerving out of his infuriated path at the last possible second. Then, just last spring, there was the time Stevie was waiting at some traffic lights when Russell Brand happened to pull up on a bicycle beside him, and Stevie in a flash dismounted, propped his bike on the kerb and, without any invitation, embraced Brand while declaring loudly enough for Stevie’s companion at the time to catch it on his phone: Mercedes-driving cyclist hug! Yay!

Young Osmer had been employed at the Gazette for almost five years. As a student at Warwick he had been extraordinary, ending up with the top first in his year, or indeed in several years. And then he had stayed on to do a PhD, working on language and class in the later novels of Dickens. But he failed to complete. Indeed he never really started. He read voraciously. He compiled file after file of notes. He knew Our Mutual Friend and The Mystery of Edwin Drood practically back-to-front. He had read more or less every academic article and monograph published on Dickens in the preceding fifty years. He knew everything that was worth knowing about theories of language and society, Victorian England, the history of the novel, Marx, ideology and class struggle. He read around his topic too. Besides all the novels and short stories of Dickens, Stephen Osmer prided himself on having read the collected novels of Wilkie Collins, Hardy and Trollope, not to mention all the Georges (Eliot, Meredith and Gissing). Yet, when it came to putting this knowledge and breadth of reading into practice, he found himself quite paralysed.

As an undergraduate, especially working under exam conditions, he would toss off scintillating essays time after time. It was no bother at all. But as he moved on to his postgraduate studies something closed. He failed to notice. It resembled a sleight-of-hand worthy of late Dickens himself. Initially the supervisor had supposed Osmer’s difficulties were related to the sheer amount of reading he had been doing: in his first year of postgraduate studies he had been left very much to his own devices. The professor had also been one of his undergraduate tutors and was, after all, well aware of Osmer’s intellectual candescence. No one, least of all the supervisor, doubted that this budding young scholar had a great academic career ahead of him.

A supervisory session would consist of an hour’s discussion of, say, Mayhew’s London or the representation of China in Edwin Drood, and the senior academic would be left wavering between intimidation at Osmer’s knowledge and articulacy, and the increasingly pressing obligation to encourage the young man to get his ideas down on paper and draft a chapter or two. Sixteen months went by and still Osmer had come up with nothing. In January he was summoned.

– It’s becoming problematic, Stevie. You’re now a full term late with getting your thesis topic confirmed. If you want to get upgraded to doctoral status you really need to get the outline complete and at least a sample chapter drafted.

But it was futile. Osmer could write notes and even discrete paragraphs without difficulty, but from the accomplishment of a coherent doctoral research outline, let alone a full-length thesis chapter, he was utterly blocked. It was, he told his supervisor (to whom he disclosed very little of a non-academic nature), like riding a bicycle into a sandpit. The professor set him up with some book-reviewing, hoping this might free him from the impasse. Kill two birds with one stone, he thought: get the lad’s writing flowing again, plus notch up some publications for the CV. As it turned out, the release was more dramatic than intended. Following the supervisor’s dispatch of a nicely formulated personal email, Stephen received a request to write a couple of brief notices for the London Literary Gazette. The editor was impressed and asked him down to lunch in Soho. At the end, over espresso, she offered him a permanent position on the editorial team. The young man hardly needed to consider. The following week he formally withdrew from Warwick, to his supervisor’s brief chagrin and longer-lasting relief. They would never speak again. Just ten days after that, Osmer had moved out of his cheap, spacious digs in Coventry into the cramped but charming bedsit in Bloomsbury.

The complete oeuvre of the cleverest young man in London boiled down, in the end, to just two essays and a few celebrated aphorisms.”

The sentence with which he relinquished his life, nearly five years later, came at the conclusion of an essay about the banking crisis. It was the second full-length piece of prose he produced in his days at the LLG. It was to be a feature articleAnd that, besides a handful of book notices and off-the-cuff remarks tweeted by others, was his life’s work. The complete oeuvre of the cleverest young man in London boiled down, in the end, to just two essays and a few celebrated aphorisms. The estimation of young writers cut off in their prime, or rather well before reaching it, says something about the vitality of a culture. The value accorded to a few poems by John Keats or Wilfred Owen, for example, is in part a measure of a culture’s capacity to mourn lost art, to recognise the importance of what might have been but never was. It is also a sort of cover-up: the work is quietly smothered under the veil of life. But a culture needs to dream. And when, after all, is a writer’s prime? Hadn’t Sophocles been ninety when he set down Oedipus Rex? And wasn’t Dickens himself in his prime when writing The Mystery of Edwin Drood? Indeed, wasn’t the mystery of that Mystery about the very sense of being cut off in one’s prime, in that case not only regarding the author but the story itself?

All this talk (as there was, in the wake of his death) about cut-off primes: Osmer was no fillet of steak, but neither was he a Keats or an Owen. If youth was crucial, so was the manner of the cut. To take one’s own life, like Plath at the age of thirty, is to invite being snipped from a different cloth. The spectre-thin collateral of war or early-onset tuberculosis can more readily provoke a mourning for mourning itself. But if he was no beef-steak, neither was Osmer merely Gallerte, that mix of various kinds of meat and other animal remains to which Marx refers in Das Kapital in his vicious satire on what it is to be a worker, reduced to sloppy pottage, to be cannibalistically consumed by those who run the show. Osmer was, finally, a writer. For all the paucity of his output, his writing would prove ghostly and enduring. And its effects would still reverberate in years to come.

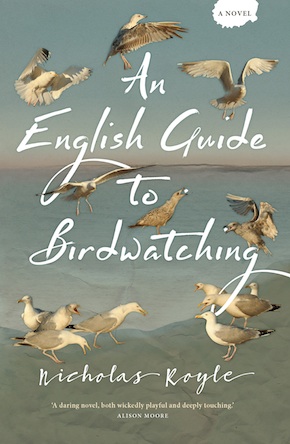

Extracted from the novel An English Guide to Birdwatching

Nicholas Royle is a Professor of English at the University of Sussex and lives in Seaford. He has written numerous books on literature and literary theory, including Telepathy and Literature, E.M. Forster, The Uncanny, Veering: A Theory of Literature and the influential textbook An Introduction to Literature, Criticism and Theory (with Andrew Bennett). His first novel, Quilt, was published in 2010. An English Guide to Birdwatching is out now in paperback and eBook from Myriad Editions.

Nicholas Royle is a Professor of English at the University of Sussex and lives in Seaford. He has written numerous books on literature and literary theory, including Telepathy and Literature, E.M. Forster, The Uncanny, Veering: A Theory of Literature and the influential textbook An Introduction to Literature, Criticism and Theory (with Andrew Bennett). His first novel, Quilt, was published in 2010. An English Guide to Birdwatching is out now in paperback and eBook from Myriad Editions.

Read more.