Into the void

by Jean-Baptiste AndreaWalk without thinking.

We have left colour behind. Everything is grey, even the green of the lichen. The path, bordered by slopes running with stones, climbs from the bottom of an immense furrow. If the mountain wanted to lure us into a trap, this is exactly how it would go about it.

Or think about something other than tiredness.

The rock sings, it chimes like crystal at each footstep. Sometimes it slips away like liquid beneath your feet, and the next thing you know you are on your knees, your hand cut open by a sharp ridge.

In 1879, Charles Marsh discovers a species that he names brontosaurus.

A shape emerges from the nothingness, a grey presence on the horizon. Suddenly there it is. A rocky face where winds and birds crash, a roar of stone thrusting towards the sky, three hundred metres above.

Marsh’s colleagues – I know them well because they are just like mine – emphasise that the fossil’s missing head makes it impossible to identify it officially. They declare that the skeleton is merely the adult version of a young apatosaurus discovered by Marsh himself two years earlier, not a new species. They shake hands and come to an agreement: the brontosaurus does not exist.

The villager releases the mules, which almost immediately set off in the opposite direction.

The brontosaurus does not exist… until someone proves that it does. Any palaeontologist would sell his parents to find one. In any case, I would sell my father, without hesitation. But to find one, I must …

Climb the via ferrata: sharp metal bars like staples in the granite, horizontal rods marking a lateral path still visible from where we stand. Thousands of pairs of feet have shaped this path before ours, this vertiginous passage where salt, tobacco, oil have been carried by men, hired dirt-cheap for the season by the salt makers of Aigues- Mortes.

You are going to die here. This is no place for the weak. You are going to die in the void with your smuggler’s dreams. And if the void doesn’t kill you, the wolves will.

Peter, Umberto and Gio are harnessed. The guide checks the equipment of the other two before taking care of me. He works without looking at me. The rope spurts like a snake between his fingers, encircling my waist, my groin, my waist again.

Tell them to go to hell. You can’t climb that.

‘You okay, Stan-eh? You’re white as a sheet.’

‘Just a bit out of breath.’

‘We’re leaving the oil cans here. Gio will come back to get them while we’re working.’

‘Welch eine unglaubliche Landschaft! What an incredible landscape! I can’t wait for Yuri to see this.’

Scent of oxide. The first steps of the via ferrata are cold as ice and I do not yet know that there will be a fifth member of our expedition.

In that instant, vertigo engulfs me, it slips between my body and the rock wall and tries to push me into the void. Below me, Peter sings as he climbs. Whatever you do, don’t close your eyes. One long blink and it’ll all be over.”

The Valley of Hell. The Devil’s Horn. This region is full of infernal names and I am beginning to understand why. With each step, with each bar that I climb, breathing in rust, my body doubles in weight. Fear steels my neck and shoulders.

An interminable wrench from the grips of gravity. This ascent is not so different from my childhood, in fact. When I told my parents that I wanted to become a palaeontologist, the Commander gave me a slap that made my ears ring until evening and told me to stop putting on airs. I would take over the family business, and that was the end of it. I confessed my scientific ambitions to Abbé Lavernhe, but God’s representative in our parish was more concerned with training the local soccer team than with science. Any answers a man might need were to be found in the Bible or in the sports section of La Dépêche, and it was pointless to ‘m’espoumper la cape de mul de craques pour bestiou’ – to cram my head full of twaddle for morons.

One day, I wanted to know why the Commander didn’t like fossils. My mother explained, in a serious voice, that you had to be beautiful to see them, to really see them. She gave me distant errands to run, errands that allowed me to search the surrounding fields. I hid my findings in the linen closet and we would admire them together by moonlight. It’s true that she was beautiful.

Another step, and another. Letting go of the main ladder to grab a handrail and follow a ledge no wider than your foot. The worst moment, the one that makes my vision flash red, the one that I must suffer through again and again, is when I unfasten the snap hook that connects me to life so I can attach it to another rope or another bar. In that instant, vertigo engulfs me, it slips between my body and the rock wall and tries to push me into the void. Below me, Peter sings as he climbs. Whatever you do, don’t close your eyes. One long blink and it’ll all be over.

Here we go, another step.

—

Stuck. So close to the top that it’s laughable. Only one more ladder, ten metres, and I’m at the summit. But if I lift a single finger, I will die. For an hour, Umberto and Peter have taken turns coming back down to encourage me, excoriate me, reason with me: I can’t fall. Even if I did fall, the snap hook would hold me in place. A rope doesn’t break – or ‘very rarely’, Peter specifies with a scientific rigour that makes me want to kill him. Gio smokes on the crest, legs dangling in the void. Say what you like, but I’m not the craziest man on this expedition.

Ten metres above me, the three men confer. Gio comes down, bouncing around at the end of a rope, the remains of his cigar between his teeth. He stops next to me, inhales a puff of smoke, then abandons it to the wind. For once, I can understand his mutterings without Umberto’s help.

‘Take your time. But we’re going on.’

He disappears upwards as quickly as he came down, sucked into the sky. I am alone.

I know Gio well enough by now to understand that he is sincere. He is ready to leave me here, to come and get me later, after I’ve fallen asleep or fainted, hanging at the end of my rope like a suicidal spider. This man, like all mountaineers, is insane, I am sure of it. I start climbing.

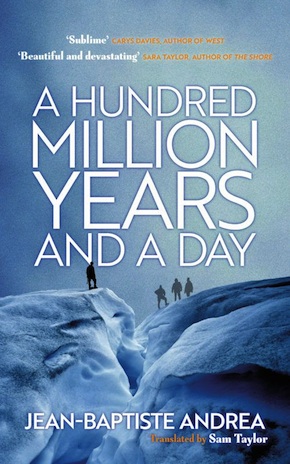

from A Hundred Million Years and a Day, translated by Sam Taylor

Jean-Baptiste Andrea was born in 1971 in Saint-Germain-en-Laye and grew up in Cannes. Formerly a director and screenwriter, he published his first novel, Ma reine, in 2017. It won twelve literary prizes, including the Prix du Premier Roman and the Prix Femina des Lycéens. A Hundred Million Years and a Day was shortlisted for the Grand Prix de l’Académie Française 2019 and the Prix Joseph Kessel 2020, and awarded the 2020 Prix des lecteurs lycéens de l’Éscale du livres. Translated by Sam Taylor, it is published in paperback and eBook by Gallic Books.

Jean-Baptiste Andrea was born in 1971 in Saint-Germain-en-Laye and grew up in Cannes. Formerly a director and screenwriter, he published his first novel, Ma reine, in 2017. It won twelve literary prizes, including the Prix du Premier Roman and the Prix Femina des Lycéens. A Hundred Million Years and a Day was shortlisted for the Grand Prix de l’Académie Française 2019 and the Prix Joseph Kessel 2020, and awarded the 2020 Prix des lecteurs lycéens de l’Éscale du livres. Translated by Sam Taylor, it is published in paperback and eBook by Gallic Books.

Read more

@BelgraviaB

Author portrait © Vinciane Lebrun-Verguethen

Sam Taylor is an author and former correspondent for The Observer. His translations include Laurent Binet’s HHhH, Leïla Slimani’s Lullaby, Riad Sattouf’s The Arab of the Future and Maylis de Kerangal’s The Heart, for which he won the French-American Foundation Translation Prize.

samtaylorwriter