Juliet West: Back to black

by Claire Fuller

“Vivid and unforgettable… a must-read.” Ann Weisberger

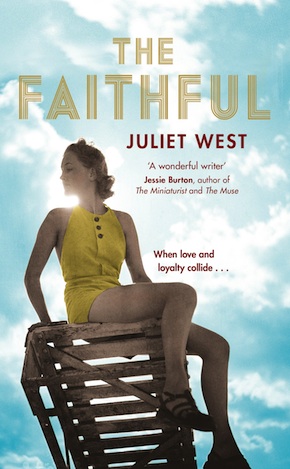

Juliet West’s second novel The Faithful is a love story set during Britain’s brief dalliance with fascism in the 1930s, and a tale of two mothers set on distinct paths. I chat to her about the book’s key issues and themes, and how she approached researching and recreating the era.

CF: I love the title of the novel, which references that many of the characters are members of Oswald Mosley’s Blackshirts and also plays with the idea of fidelity and love, which are strong themes in the book. How did you come up with it? And do titles come easily to you?

JW: Ha, not at all! I scribbled down endless ideas over the three years I worked on this novel. One of the early titles was The Summer in Black, which I liked because the first draft was set over just one summer. But as the timeframe expanded and the novel became more ambitious, it didn’t seem to fit so well. The Faithful came from a line of dialogue written as I was finishing the final draft, and it seemed to be perfect for all the reasons you’ve mentioned.

Some might say it was a bold move making the heroine a member of the Blackshirts, an organisation which is now completely despised. And although Hazel isn’t an ardent supporter she does march and do a lot to support their cause. Was this something that worried you, or did that conflict draw you to the story?

As flawed heroines go, this is a pretty major flaw, isn’t it? But you’re absolutely right – I was drawn to the challenge of trying to understand how ‘ordinary’ women were attracted to fascist movements in the 1930s. I don’t want to harp on about contemporary relevance, but I do think it’s a question that needs unraveling – how extremists exploit the fears and vulnerabilities of supposedly decent people.

The Faithful is ultimately a love story which is complicated by Hazel’s entanglement in the fascist movement. While readers may not agree with some of her decisions, I hope that, as the plot unfolds, they will begin to understand why she is drawn in. Hazel is only sixteen when the novel opens in 1935; by the final chapter she is twenty-two and a very different person.

How did the story develop? Are you a planner, did you know the ending?

The first draft took about ten months to complete, working to a detailed synopsis that I wrote once I was about a third of the way in. In retrospect, I wish I hadn’t written that synopsis, because it turned out to be a straitjacket, and I ended up with a novel that was OK, but felt to me rather hollow. I started again with a more open mind, allowing the plot to unfold over several years rather than several weeks. I’ve ended up with a much bigger book (in terms of characters and themes, if not in word count) and feel much happier with the finished result.

Strangely, the final scene has remained almost the same throughout the various drafts. It’s just how I arrived at this point that changed so dramatically!

What inspired you to write The Faithful?

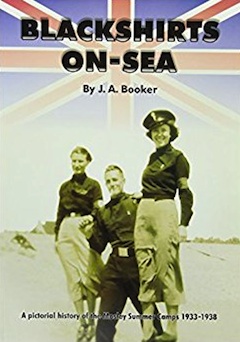

The initial spark came several years ago when I was studying in Chichester University library (at the time I was taking an MA in Creative Writing). My desk was in the history section, and the spine of a book called Blackshirts-on-Sea caught my attention. It turned out to be a pictorial history of Oswald Mosley’s fascist summer camps, which were held annually on the Sussex coast between 1933 and 1938.

The photos – fascist drum parades and camp fire concerts, Mosley and his acolytes posing in bathing trunks – were sinister and really quite bizarre, and instantly struck me as an interesting setting for a short story or novel. But it wasn’t until five years later when my agent asked whether I had any plans for a second book that I returned to the idea.

The photos – fascist drum parades and camp fire concerts, Mosley and his acolytes posing in bathing trunks – were sinister and really quite bizarre, and instantly struck me as an interesting setting for a short story or novel. But it wasn’t until five years later when my agent asked whether I had any plans for a second book that I returned to the idea.

At the end of the novel you list many books that helped you with your research. The story felt very thoroughly researched, without being dry. How did you set about researching the period and the politics?

Thank you – it’s always tricky to know how much to include and how much to leave out. History books and academic publications were the first port of call, providing detailed analysis and relative impartiality. I also delved into the literature and propaganda of the time, spending hours in the British Library leafing through old copies of The Blackshirt (the weekly newspaper of Mosley’s British Union of Fascists). I knew that I would find this literature disturbing, but – given that this was a legal and widely-distributed publication – I was truly shocked by the violence and vitriol of the paper’s anti-Semitism. The language became ever more sickening after the Battle of Cable Street in 1936. Astonishingly, Mosley always claimed not to be an anti-Semite (on YouTube you can watch his interview with David Frost in in 1967. Chilling).

I also researched the Spanish Civil War, as one of my characters is a communist who joins the International Brigades. Again, history books were useful, but personal accounts proved the most vivid, for example memoir and poetry, as well as oral history including the Imperial War Museum’s sound archive – a magnificent resource.

You’re also a short-story writer and poet. Do either of these inform your novel writing?

Hmm, I think it’s more accurate to describe myself as an apprentice poet. (I recently attended a series of workshops with real poets, which was incredibly inspiring but also made me realise how much I have to learn.) I think in both poetry and short stories there’s a greater sense of discipline – the need to convey a mood or an emotion in a very confined space – and this appeals to me. In a sense it’s closer to my previous job as a news reporter, condensing complex information into something digestible. Novels, by contrast, are huge and daunting and massively risky. But yes, I think those shorter forms do influence the way I approach a novel. I try to break down a longer project into manageable chunks: a scene is a short story; a sentence might have the rhythm and precision of a line of poetry. The challenge is in linking those scenes and sentences to become a coherent whole.

While there was an awful lot of research and character development, I always had the architecture of the novel – the real events – to keep me on track.”

Another theme in The Faithful is motherhood and its difficulties. The mothers in the novel relate to their offspring in different ways. Was this something you deliberately wanted to focus on?

This wasn’t part of the original plan, but seemed to evolve over time. Bea and Francine are two very different mothers – one fiercely protective, the other decidedly laissez-faire – and it was fascinating to explore this and the different ways in which their children rebel as young adults. It’s an eternal question for parents, isn’t it – how to find the right balance between discipline and freedom. Perhaps it’s significant that Tom is an only child, and so is Hazel. Their relationships with their mothers are unusually intense. That can be a positive, I’m sure, but in this book it leads to conflict…

Everyone talks about the ‘difficult second album’. Was The Faithful harder to write than Before The Fall?

Definitely. Before the Fall was based on a true story, and while there was an awful lot of research and character development, I always had the architecture of the novel – the real events – to keep me on track. The Faithful is far more ambitious in terms of character and theme. I can’t lie – there were times when I cursed myself for embarking on something so complex. Fortunately, at those moments I was able to talk everything through with my agent and editors. The trick was to focus on the heart of the novel – the love story – and not to get too bogged down in the wider themes.

I really liked how you handled the attitudes to sex outside of marriage in the 1930s, especially in regard to how women were viewed then. Is this something you feel strongly about?

I’m definitely interested in writing about women who transgress, sexually or otherwise. What has come through very strongly while researching both books is that women have never been afraid to experiment sexually – there was always a good deal of sex before marriage, and sex outside of marriage, etc. – but in the earlier decades of the twentieth century there was far more hypocrisy and cant. Women who broke taboos were ostracised and roundly condemned, whereas men were more likely to be excused in the ‘boys will be boys’ vein. Double standards are still rife of course, but we have made some progress I hope.

Finally, what are you working on next?

I’ve been working on a couple of short-story commissions and I’m also experimenting with flash fiction. Perhaps it’s something to do with having three teenage children at home, but I need a moment to build up my energy before knuckling down with book three!

Juliet West grew up in Worthing and studied History at Cambridge University. She worked as a journalist before taking an MA in Creative Writing at Chichester University, where she graduated with distinction and won the Kate Betts Memorial Prize. Her first novel Before the Fall was shortlisted for Myriad Editions’ First Drafts competition and is published in paperback by Pan. The Faithful is published in hardback and eBook by Mantle and as a digital audio download by Macmillan.

Juliet West grew up in Worthing and studied History at Cambridge University. She worked as a journalist before taking an MA in Creative Writing at Chichester University, where she graduated with distinction and won the Kate Betts Memorial Prize. Her first novel Before the Fall was shortlisted for Myriad Editions’ First Drafts competition and is published in paperback by Pan. The Faithful is published in hardback and eBook by Mantle and as a digital audio download by Macmillan.

Read more

julietwest.com

@JulietWest14

Author portrait © Kelly Hill

Claire Fuller was born in Oxfordshire in 1967 and gained a degree in sculpture from Winchester School of Art. After a career in marketing she began writing fiction at the age of 40. She has an MA in Creative and Critical Writing from the University of Winchester and lives in Hampshire with her husband and two children. Her first novel Our Endless Numbered Days won the Desmond Elliott Prize. Her second, Swimming Lessons, is published by Fig Tree in hardback and eBook.

Read more

clairefuller.co.uk

@ClaireFuller2