Lily Bailey: OCD and me

by Mark ReynoldsAs a child and teenager, London-born Lily Bailey suffered from severe obsessive compulsive disorder. From as early as she can remember, there was always a second voice in her head, filling her brain with intrusive, uncomfortable thoughts convincing her she was a bad person liable to bring only pain, grief or disgust to others. She began making lists of everything she was obsessing over, and inventing mental and physical rituals to absolve her perceived faults, which meant she spending hours on end sitting in her room performing her ‘routines’ – until the whole exhausting process began afresh.

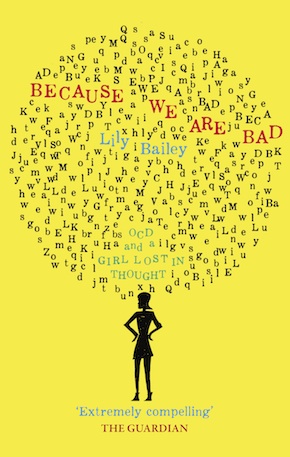

After many years of pent-up, isolated personal battles she was finally referred to a psychiatrist and diagnosed with OCD at 16, and has since been able to embark on a gradual recovery. Because We Are Bad is a frank and insightful memoir of her life up to the age of 21 – she is now 24 – written to help others deal better with the same diagnosis. Witty and emotionally engaging recollections and observations are tinged with debilitating anxiety and a shocking bid to end her life during a desperate relapse when she went to study English at Trinity College Dublin. Abandoning her degree, with the help of expert counselling and the support of family and fellow sufferers, she has since found a path to managing her obsessions and compulsions while making impressive inroads as a model and writer. As we meet opposite the BBC’s Broadcasting House in the middle of a hectic day of media work, she is bright and buzzing.

After many years of pent-up, isolated personal battles she was finally referred to a psychiatrist and diagnosed with OCD at 16, and has since been able to embark on a gradual recovery. Because We Are Bad is a frank and insightful memoir of her life up to the age of 21 – she is now 24 – written to help others deal better with the same diagnosis. Witty and emotionally engaging recollections and observations are tinged with debilitating anxiety and a shocking bid to end her life during a desperate relapse when she went to study English at Trinity College Dublin. Abandoning her degree, with the help of expert counselling and the support of family and fellow sufferers, she has since found a path to managing her obsessions and compulsions while making impressive inroads as a model and writer. As we meet opposite the BBC’s Broadcasting House in the middle of a hectic day of media work, she is bright and buzzing.

MR: In what ways do you find OCD is generally misunderstood, and how did you set out to put that right in this book?

LB: I guess most people, myself included before I found out I had it, think OCD is all about liking things straight and tidy, that it’s like a cute little quirk that makes you really organised, and it’s not remotely uncomfortable. Well actually, to be diagnosed with OCD you have to spend more than an hour a day doing your compulsions – most people spend far longer than that – and it has to cause you serious distress. Even if you spend two hours tidying your house every day, if that brings you joy it’s not OCD.

Even my old doctor was saying, ‘I finally understand. I feel in this book I understand you more than I did before.’ So it’s freeing, but I guess having people know so much about your life is one of the drawbacks too.”

Which part did you write first, and how quickly did it come together?

The first bit I wrote was when I’m at school and I’m in my “I’m not doing this anymore and I’d just like to go home” phase and I get my diagnosis. From there I just popped all over the place. It wasn’t written as it’s read, I sent the publisher random chapters. I think the final chapters were the only part that was written in order.

How did it feel when the book first came out, and what have been the highpoints and drawbacks of having your inner world put out there?

It was bizarre because suddenly my family and friends, and even my therapist, my old doctor, was saying, “I finally understand. I feel in this book I understand you more than I did before.” So it’s freeing, but I guess having people know so much about your life is one of the drawbacks too. Obviously my family isn’t always portrayed in the best light. I don’t think I present them as terrible people, I just think my parents come across as two people dealing with a child with a mental health condition that they’re really struggling to handle. I know that members of my family are a bit like “God, did you have to write that about us?” But I did feel it was important to paint a true picture, and actually I’ve had loads of parents and family members of people with OCD reach out to me and say it was really helpful to show that parents aren’t always perfect.

The fact that everyone can read about my life now, I find sometimes creates an imbalance. Like I could meet someone and they could read all about my life, and I might not know the first thing about them. I started a new relationship, and my boyfriend was like, “Oh, shall I read it?” and I said, “No, I want you to know everything that’s in the book, but I want you to find it out at the same time as I’m finding out stuff about you, because if you read the book I almost become like a fictional character, and I’m not a fictional character, I’m your girlfriend.”

Two revelatory moments stood out for me: the early short chapter ‘My Friend’, when you realise your imaginary companion has a more menacing agenda than those of your schoolmates; and then where you feel so quickly at home in the first support group you attend. How important were each of those moments to you?

“Searing… funny, eloquent and honest.” Psychologies

The first moment I guess is important because it was a realisation that I was different. But then when you’re a child new things happen every day, so it didn’t seem that big a deal. The support group was massively more important. That was a turning point in my life, and I always say that one of the things to do if you have OCD – if you’re just finding out, or if you’ve had it for a long time and you’ve not known what to do about it – is go to a support group, and if you don’t have one locally, set one up.

How easy is it to do that?

It’s not as hard as you might think, because there are really great charities like OCD UK and OCD Action who are quite proactive about helping you set up a support group. And also with social media, if you put it out there, you’d be surprised by how many people near you there are who want something like that. Also you don’t need a massive budget. At the support group I went to, for instance, all the people contribute a pound each time, and we always say if you can’t contribute you don’t have to. Obviously with something like therapy you do need a big budget, and that’s why the waiting lists on the NHS are so long because it’s so strained. But a support group is relatively easy to do.

Your OCD expressed itself in many different ways throughout your childhood and adolescence. Do you think it could have been diagnosed sooner? How can teachers, parents and the general public be better informed about spotting the signs and understanding the illness?

I think it definitely could have been diagnosed sooner. I don’t necessarily blame my parents for that, because they were aware that something was up, but they just didn’t know quite what it was. Because, like I was saying, there are so many misconceptions about it. I used to do all sorts of weird things with my body, like tapping, tapping, tapping, and doing this with my feet and doing that with my hair, and they just didn’t really know what it was. I think they just thought I was quite an anxious child, and I would probably grow out of it.

OCD’s the fourth most common mental health condition, at any time it affects between one and two per cent of the population, so most people know someone who has it. Simply put, OCD is just obsessions, the thoughts that are intrusive and uncomfortable, and compulsions, which are the actions you take, whether physical or mental, in response. And if everyone just knew that, things would start to make a lot more sense. I do think awareness has improved a little bit, but to give you an example, I remember when I was diagnosed and one of my teachers was told about it, the first thing she said to me was, “Don’t worry, you’ll be OK. I worked at a previous school where there was a girl and she had really bad OCD, not like you. She had to wear gloves the whole time, she couldn’t sit anywhere without putting newspaper down, she was much, much worse than you.” And I remember feeling, “No, you don’t understand. This has ruined my life. Just because I didn’t know it was OCD and you didn’t know it was OCD, and it’s not the kind of OCD that you expect it to be, it doesn’t make it any less valid.”

Your therapist taught you to understand that your routines feed off isolation, and that it was important to expose yourself to the company of others. How did that work for you?

Well, when I’m in a really bad place with my OCD, I’m overwhelmed by obsessions coming in, and if I’m by myself all alone, then I have all the time in the world to engage with them. But when I’m with other people, my obsessions might be going da-da-da-da-da, but so are the other people, drowning them out. So, as I say in the book, on one hand the worst thing about OCD is being with other people because I can’t do my routines, but also the best thing is being with other people, because then I’m distracted. Most people like to think that they socialise just because socialising in itself is a pleasure, but for me it really wasn’t, it was like, “Right, now I must do something sociable!” I’m a lot more sociable now than I was, but it was a gradual process.

My psychiatrist used to describe exposure therapy as like being your own scientist, I quite like that. You’re testing out these ideas that you’ve held for so long and finding out, is that actually true?”

And how did cognitive behavioural therapy [CBT] and exposure therapy work for you?

CBT is a kind of talking therapy which is not like traditional psychotherapy in that it’s not so focused on the past and on underlying feelings and emotions. It’s very much rooted in the present, with the goal of changing the current behaviour. For people with OCD the main thing we do in CBT is exposure therapy, where you put yourself in amongst the obsessions that cause you so much stress, and rather than doing what you’ve been doing for years and going along with them, you experiment with a different behaviour. Like the socialising in place of isolation. Or say I’m worried I smell bad, then I have to not shower for a couple of days and hang out with all my friends and figure out whether it’s a real issue. My psychiatrist used to describe it as like being your own scientist, I quite like that. You’re testing out these ideas that you’ve held for so long and finding out, is that actually true?

Have you tried any other treatments since the book was written?

In the book I’ve only had CBT. Now CBT’s great, I do not wish to diminish it, but I do think that you can kind of come to the end of the road with it. Ultimately what CBT is saying is “feel the fear and sit with it”. It’s actually quite simplistic. Of course it’s a nightmare to do, but there comes a point where you know it all. After the book was written I was referred for a Treatment-Resistant OCD course on the NHS, and I ended up not completing it. I went in and the therapist was writing ‘Obsessions’ and ‘Compulsions’ on the whiteboard and defining them, and saying, “Let’s make a list of your obsessions and your compulsions,” and da-da-da-da-da. And I had done this so many times. For God’s sake, I’ve written a book about it! I went for a few sessions and I had to tell her it was just not helping. I could have a PhD in CBT at this point, I had to try something different. So I have since been having integrative therapy with a great psychotherapist, which is a bit of everything really. There are some cognitive behavioural aspects to it, I suppose, but I’d say it’s much more psychodynamic, and I really love that and find that it’s helping me in completely different ways. So the first clinical recommendation is to be treated with CBT and I don’t dispute that because I think in crisis that’s a really good treatment method, but I don’t think it’s the only thing that can help.

Why do you think things spiralled so badly out of control for you in Dublin?

It was probably being away from the support network of the doctor I’d been seeing, and I don’t know if I’d also say the support network of my family, because whilst my family have been extremely supportive, I’d been at boarding school so it wasn’t like I’d never been away from home before. But because I was self-medicating, which a lot of people with OCD and other mental health issues do, I was on quite a lot of anti-psychotics, which I don’t think were necessarily great for me, and I was drinking a lot and not really sleeping, and not looking after myself at all, plus I was away from my doctor. So I think it was a combination of all those things.

One of the really entertaining episodes in the book comes when you team up with a girl called ‘Frankie’ at the psychiatric hospital and go about breaking all the rules. Did messing about with her help your recovery, or was it just a diversion and rebellion against the suffocating regime?

I think it definitely did help, it was probably the only good thing about being in that hospital. Like I said about the support group, companionship is not to be underestimated. This was a different kind of companionship, but I hadn’t had fun in such a long time, and I guess with her it was almost like having constant exposure therapy because I was just not able to engage with the stuff my illness wanted me to.

How often do you still have bad days, and how do you go about putting them behind you?

A few months ago I had quite a bad patch, but it’s a bit different now because I have this understanding of what it is, and I am much more open with my friends and family, it’s not like I’m still bundling it all up. Before I would just sit in my room because I thought that was the best thing to do and there would be fewer compulsions if I just sat very still; now I realise that’s just not helpful. So whilst I do allow myself to have the odd duvet day, because I think that’s healthy too, if it’s getting into prolonged isolation I’m like, “Right, I need to get out there.” Even if it’s just walking my dog.

Do you foresee a day when you’ll be fully recovered, or is that not even a useful target?

I don’t know, people with OCD are really divided on whether you can recover, and in my experience the people who have got completely better think, “Yes you can! Recovery for everyone, and don’t settle for anything less!” And then the people who can’t are like, “No, you never can, it’ll always come back. You think you’ve recovered but you haven’t, so don’t get complacent.” And I don’t think either of those viewpoints are especially helpful. I think, bottom line, what you definitely can do is get better – and by better I don’t mean recovered, I mean you can significantly improve your situation, and some people seem to make a full recovery and some people don’t, and we don’t completely know why that is, but it doesn’t seem to be linked necessarily to the quality of therapy. I’ve had brilliant therapists for years, and I still experience a bit, so I don’t think it is completely down to the right kind of help – although obviously if you haven’t had the right kind of help, then that can be a perpetuating factor.

But better is good…

Yes, better is good – I’ll settle for better!

We probably need two words, a word for a negative and unhealthy obsession, and a word for just really liking something, because they are just not the same thing.”

How would you describe your relationships with family today compared with before?

Good. They’re more open than they were and more real, and I’m more me than I was. My mum in particular is my rock, she’s an amazing person, and I feel a bit bad if she sometimes comes across in the book as not being so, because she really is, but I just wanted it to be an honest portrayal. It’s my story, but it’s also the story of parenting someone who has OCD.

With my sister things are good too. When I was growing up she used to just think I was this kind of perfect big sister who got all-As and toed the line and never offended anyone. And in fact my OCD was centred around trying to be normal and perfect. Now I think she has a much more real view of me, which is nice – and probably better for her as well.

Is there room for positive obsessions in your life?

Is there room for positive obsessions in your life?

Yeah, definitely. I think it’s a shame that in our language ‘obsession’ can mean both things. We probably need two words, a word for a negative and unhealthy obsession, and a word for just really liking something, because they are just not the same thing. But yeah, definitely. I’m obsessed with my dog Rocky, I’m obsessed with reading, I’m getting slightly obsessed with Doctor Who, because my boyfriend is really into it and he’s kind of converted me. In fact I’m more in to Doctor Who than I’d like him to know. He bought me action figures for Christmas, and I was all like, “Oh, this is a present for you, isn’t it?” But actually I was thinking, “Yes! He got me a Sarah-Jane! And K-9!”

This is a memoir, not a self-help book, but it does describe a path towards recovery. So what have been some of the best responses you’ve had?

The thing I love the most is when someone says to me, “This made me feel like I wasn’t alone, it was a real source of comfort and even friendship.” Because I wish I’d had something like that. And you’re right, it’s not a self-help book, but there are particular things I describe, for instance putting off the compulsions and going to the support group, and just even talking about it in the first instance, which sufferers have said to me have been really helpful.

Having put yourself out there as OCD Girl, what else do you want to tell the world about?

After I wrote this book, I was thinking I’d jump back in and write the next thing, but I kind of exhausted it for a bit writing this. So I’m doing quite a bit of modelling at the moment, and obviously promoting the book, and kind of thinking what’s my next move going to be. But I know what it’s not going to be, it’s not going to be journalism. The only journalism I’ve done recently has been OCD-related. In fact I wouldn’t call it journalism, it’s my life. I’d love to write another book, but I’ve got no idea what it’s going to be yet.

Might it be fiction?

That’s what I’ve always wanted to do, so yes, maybe, if I can get my writing brain back in gear. I used to think writers’ block was something people would claim they had if they couldn’t be arsed to write – which was a very pretentious teenagery thing to think. I’d never had it, so I just thought everyone who had it was just being lazy. Then it happened to me and I was like, uh-huh, so this is real…

What other plans are on the horizon?

Well, currently I’ve got all this book stuff going on and it’s coming out in America and Germany, which is exciting. It was out in Australia too last year and it was great to be able to travel with the book there, that was something I never thought I’d be doing. The modelling is ongoing and I also work part-time as a support worker for young people with disabilities. I love that, it uses a completely different part of my brain. But I wasted so much of my life doing all this obsessive-compulsive stuff, and so now I’m just kind of taking things as they come.

Lily Bailey is a writer and model based in London. Because We Are Bad: OCD and a Girl Lost in Thought is published in paperback, eBook and audiobook by Canbury Press.

Read more

lilybailey.co.uk

@LilyBaileyUK

International editions are published by Allen & Unwin in Australia, Harper in the US, and Bastei Lübbe in Germany (July 2018).