The masterful Margarita

by Charlotte CoombeFrom the moment I began reading them, I loved everything about the two novellas and story collection that comprise Margarita García Robayo’s Fish Soup. I found the author’s voice incredibly compelling and felt an instant connection. I could relate to the detachment, the darkness juxtaposed with understated humour, the sense of wanting to get away, of finding ways to escape the situation you are in… Sometimes, there is just something about an author’s voice that resonates so perfectly with you, and you feel exactly what they want you to feel. Deborah Levy is one of those authors for me. I recently read her story collection Black Vodka, and drew a lot of parallels with García Robayo. The books I enjoy most are acutely psychologically perceptive, and deal with love, illness, death – all the big things – with a controlled, yet poetic style. Through her various characters and scenarios, García Robayo intricately examines every aspect of this thing we call life, painting just enough detail so the reader can see through the cracks.

The first time I read the original of Waiting for a Hurricane in Spanish, I automatically started translating in my head as I was reading. For me this is always a good sign with any book I read in another language; it means I can hear the voice, I relate to it and I am simply itching to put it into English. Of course, there are always some unfamiliar terms or vocabulary (as translators, we have to look up a lot of things in the dictionary and this is not – as some friends of mine think – ‘cheating’!), or even cultural-specific references, but overall, the voice instantly spoke to me and I could not wait to start translating, to find ways to replicate and make her prose work the same way in English. I was utterly drawn in.

García Robayo’s writing is insightful into the human condition, delving deep into all the nuances of what it means to be human, to be flawed. Each character in each part of the book, in each story, is going through something. They are all trying to find ways to deal with what life throws at them, finding survival strategies. For that’s what life is: just one big survival strategy.

I read Waiting for a Hurricane first, and absolutely loved the detached style of the narrator. There is a blunt poetic dimension to her style that adds complexity to the way in which the female protagonist is so desperate to leave her country, so detached from her surroundings and from her own emotions. There is disillusionment in bucketfuls, but the little dashes of humour prevent you from drowning in despair. This is an author who can make you question the very meaning of life, love and mortality, then in the next line she makes you laugh out loud. Although she paints a bleak picture at times, rather than leaving the reader hopeless, there are constant small affirmations that things are going to be fine. That we can all find ways to cope, even if the methods are unconventional. The protagonist in Waiting for a Hurricane finds small connections with other people (the storytelling local fisherman Gustavo, her little nephew in LA), no matter how hard she tries to resist them. In this way, she develops and discovers more about herself than she realises, or lets on. And this is the key to García Robayo’s beautifully executed dissociative narrative style.

García Robayo’s writing is insightful into the human condition, delving deep into all the nuances of what it means to be human, to be flawed.”

With the collection of short stories Worse Things – perhaps a more carefully crafted and mature work, which earned her the prestigious Casa de las Américas prize – I fell even more in love with her writing. García Robayo is extraordinarily skilled at creating snapshots of people in extreme situations, be it illness, grief, old age, losing a child, a break-up, a breakdown, an existential crisis… Yet she does so in a way which is pared down and emotionally detached. She does not waste words; every sentence counts with her precise prose. One of my favourite stories in the collection is the very impactful ‘Sky and Poplars’. The broken parent-daughter relationships; the situation of the female protagonist, which slowly dawns on you as the story progresses; I was actually moved to tears as I read it, and then again as I translated it, which is a first for me. The sense of being trapped, of being in emotional turmoil but trying to hold it all in, these are themes that pervade all the texts and bring them together. Motherhood is also a recurring theme. Similarly to writers like Ariana Harwicz, Samanta Schweblin, Lina Meruane, much of her writing revolves around frayed family relationships, something that will certainly strike a chord with most readers. García Robayo is most definitely a master of observation, a master of depicting relationships that seem beyond repair, whether it is with family members, a lover, or oneself.

Sexual Education was the text I translated last. It is a novella with a nameless protagonist, like Waiting for a Hurricane, but in many ways it differs from it and from the stories of Worse Things. In Sexual Education, García Robayo depicts the turmoil of being a teenage girl in a strict Catholic school, which she is desperate to escape, while at the same time experiencing the sexual awakening so particular to those years, when hormones and imagination are raging. The narrative voice is biting and bold, and as I translated it rapidly became my favourite text of all three. I was able to exercise my creativeness with some of the sexual, dreamlike or graphic imagery, the slang and nicknames, while maintaining her trademark humour and cynicism throughout. There were real laugh-out-loud moments in this, as well as flashes of pure poetic beauty, which made it a joy to translate.

Many of García Robayo’s characters are strong and fiercely independent, which clearly reflects the author’s personality. Emotional detachment from everyone who surrounds them is something all the characters in her writing share. This is a thread that brings all her writing together, and it is one of the things that makes the collection work so beautifully as a whole.

No two translations will ever be the same because no two translators have the same knowledge and life experience, which influence each and every one of the decisions made during the process.”

The voice and the tone, which can often be the biggest challenges for a translator, were easy to find each of the works. I ‘got her’ straight away, and the translation seemed to flow fairly well. The challenges for me were more specifically related to vocabulary and word choices, further down the line, when you start deliberating during the editing stages. As with any book, there were some things that took time to work out, and some that I was able to clarify with the author herself during the editing stages. There are always a few words or expressions that you presume everyone uses in the same way as you, but you then discover nobody else says. It might just be something you grew up with in your family, for example. Not usually things you check, these are instinctive word choices, you don’t see anything amiss, and you move on. This self-editing process is one of the hardest things about being a translator: picking up on things that might not sound right to another reader, when it your head it sounds perfect. This is where the copy editor and editor (in this case, Fionn Petch and Carolina Orloff respectively) come in and do their work, and it is always highly beneficial to have a couple more people combing through the text, tweaking, questioning and suggesting, until you have moulded the text into a shape you are satisfied with, and which does the original justice. No two translations will ever be the same because no two translators have the same knowledge and life experience, which influence each and every one of the decisions made during the translation process; but pooling this knowledge during the edit helps enormously as you endeavour to match that highly original and exquisite voice you first encountered.

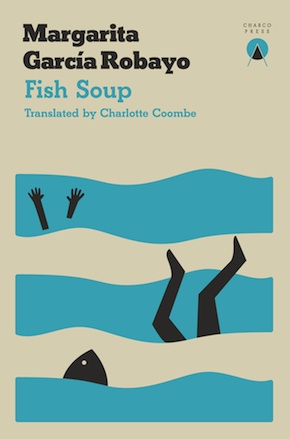

Margarita García Robayo, born in Cartagena, Colombia, in 1980, is the author of three novels, a book of autobiographical essays and several collections of short stories, including Cosas peores (Worse Things), which won the Casa de las Américas prize in 2014. Her books have been published throughout the Spanish-speaking world, and have been translated into French, Portuguese, Italian, Hebrew, and Chinese. She lives in Buenos Aires. Fish Soup, translated by Charlotte Coombe, is published in paperback by Charco Press.

Margarita García Robayo, born in Cartagena, Colombia, in 1980, is the author of three novels, a book of autobiographical essays and several collections of short stories, including Cosas peores (Worse Things), which won the Casa de las Américas prize in 2014. Her books have been published throughout the Spanish-speaking world, and have been translated into French, Portuguese, Italian, Hebrew, and Chinese. She lives in Buenos Aires. Fish Soup, translated by Charlotte Coombe, is published in paperback by Charco Press.

Read more

@CharcoPress

Author portrait © Mariana Roveda

Charlotte Coombe is a British literary translator, working from French and Spanish. Her translation of Abnousse Shalmani’s Khomeini, Sade and Me (2016) won a PEN Translates award in 2015. Her recent translations include Ricardo Romero’s The President’s Room (Charco Press, 2017) and Eduardo Berti’s The Imagined Land (Deep Vellum, 2018).

Charlotte Coombe is a British literary translator, working from French and Spanish. Her translation of Abnousse Shalmani’s Khomeini, Sade and Me (2016) won a PEN Translates award in 2015. Her recent translations include Ricardo Romero’s The President’s Room (Charco Press, 2017) and Eduardo Berti’s The Imagined Land (Deep Vellum, 2018).

cmctranslations.com

@CMCTranslations

Author portrait © Charlotte Coombe