Mr Cunningham’s feelings for snow

by Farhana Gani

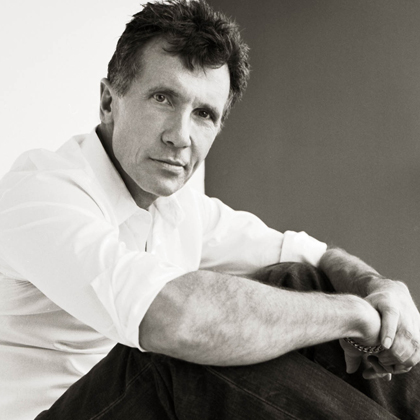

Author portrait © Richard Phibbs

Michael Cunningham’s best-known work is the Pulitzer Prize-winning sensation The Hours, about three women whose lives intersect across the 20th century. His latest novel features another trio of characters, but this time their lives are more directly entwined.

The Snow Queen opens in 2004 on a wintry New York day as Barratt Meeks, a 30-something underemployed Yale graduate who has just been dumped by text is stopped by a light in the sky above Central Park, “as he imagined a whale might apprehend a swimmer, with a grave and regal and utterly unfrightened curiosity.” It’s a light like no other – a secret sign that prompts Barratt to start going to church.

Barratt lives with his older brother Tyler and his fiancée in their shabby Brooklyn apartment. Tyler is a struggling musician desperately trying to write a song for his wedding to Beth who is hopelessly ill. He also has a secret drug habit.

The brothers are close and take their dead mother’s order to look out for one another to heart. Their unusually loving relationship is at the core of this beautifully crafted and penetrating novel. There is kindness and generosity between the starkly different brothers; both are tormented by fear, loss and creative disappointment.

FG: The Snow Queen is also the title of Hans Christian Anderson’s fairy tale. Why did you choose it?

MC: Titles are funny. I usually know the title when I start writing. You know, this is a book called ‘whatever’ and let’s see what happens…. I had some discussions with my editor about using the title of the fairy tale. You know, five out of ten people would ask you to tell you the story of The Snow Queen, it’s really not that well known. We know it’s a Hans Christian Anderson story but we don’t know that it’s a dark – and weird – story. And there’s no way of saying this without sounding pretentious, which I actually am! I think I was thinking not so much directly of the fairy tale as I was of whatever Hans Christian Anderson, a better writer than I, was thinking of when he wrote the fairy tale – you know the shattered mirror that lodges in people’s eyes.

You start and end the novel with an homage to the fairy tale. And you playfully scatter certain words throughout; and there’s Beth and her hair and the mark of the witch. I enjoyed the allusions.

Good – and those are obviously allusions to the fairy tale but it’s not a literal post-modern retelling. Like I said I feel like I was going back to the time of Hans Christian Anderson when he was sitting in a room in Copenhagen, I guess, and thinking “what is this thing?”. Fairy tales are for people who need rescuing, but not often about characters who need to be brought back to themselves, who have been spiritually and psychically altered. Rapunzel has to get out of the tower but all the prince has to do is get her out of the fucking tower! She hasn’t been changed by being in the tower; she hasn’t been awakened. And I wanted more than the literal events, that sense of distortion feeling like clarity.

In developing Tyler and presenting the points you just made through him, can you share how you created and shaped him?

Part of what is interesting about Tyler is his drug habit. Because the only story I’ve ever been told about those kinds of fears of drugs is simplistic and moralistic. And its essential message is: you are weak and you are foolish and you have to stop this right now. And I’ve been thinking: isn’t it a lot more complicated than that? Isn’t the desire to enhance and be yourself by means of illegal substances various and particular to individuals?

Tyler’s relationship with drugs is not his essential human quality. I did want to write a character who not only does drugs – or does them for more interesting reasons than escape, who is trying to force open a door that has otherwise been locked. We leave Tyler at an ambiguous point, we don’t leave him dead in an alley with a needle in his arm, which is where stories about drug addicts almost always end up. You know, I’m tired of that story. I’m tired of living in a country which has the biggest incarcerated population in the Western world largely because of draconian drug laws. And I’ve had it, I’ve just had it with Nancy Reagan and all those moralistic, simplistic fools and assholes who take a problematic but really human search for transcendence and turn it and just throw people in jail. I wish Nancy Reagan was still alive so I could throw this book at her!

In reading your book and being drawn to Tyler as a strong character, it’s not his drug habit that defines him…

… which I’m really glad about. You start from something and that gets knit into the larger fabric of the character.

It was his creative process I was drawn to: “The growing unease in the region of what he can create and what he can envision,” All creatives go through that, right?

I think it comes with the job. It should. You should have a better novel in mind than you’re able to write. Not only because you yourself have one but because there are aspects of the story you want to tell that can’t be conveyed in language.

So you find language limiting?

I do. I do. I find it fabulous. I love language. But I think – you and I on this Monday morning have things that we just can’t express.

All the time! Searching for words that just aren’t there.

Because they don’t exist. Not because you can’t bring yourself to say it, but because there’s no vocabulary for certain elements of human experience.

And yet… I came across a wonderful word a few years ago: Kummerspeck.

What is that?

Well, Speck is bacon, and Kummer I think is to do with grief, so the literal English translation from the German is ‘grief bacon’, and they use it to express the type of grief that results in overeating.

Wow! Wow! Wow! You know, German is great! There’s a downside to German, it’s harsh and ugly-sounding. But the vocabulary is amazing. there’s an incredible array of words in the dictionary for states of feeling for which there is no English equivalent. English is rich in synonyms. One of the great things about writing in English is that there are seven or eight different words for everything which is not so in a lot of other languages. Every language has its strengths and weaknesses and English is a little limited in its vocabulary for states of mind and conditions of being.

So Barratt and Tyler are brothers who love each other and have a curious desire to protect one another because of their long-dead mother. She has her own story arc running through the novel, but although their mother left them with a common goal to look out for one another, their individual childhood recollections are so very different.

She’s not exactly the ‘Snow Queen’ of the title. But she’s a certain figure of a fairy tale – an enchantress – whose most lasting spell was to pull each of the boys aside and say: you have to look out for the other one.

They’re also very kind to each other.

They are. And their relationship is also confined. And they need to separate a little, which begins to happen as events unfold.

The book opens with the trio – Barrett-Tyler-Beth. And then along comes Liz. What a force!

It’s like Tyler, you start with a certain idea and a person forms around it. I wanted to write about a hot 58-year-old woman. She can pass for 35, you know, she’s hot shit and she’s of a certain age. I get so tired of women in fiction – and everywhere – being done at 26. We’re all tired of that too. She’s really hot and not apologetic about it.

As you’ve described her, “she knows the story of human desire, in all its squeamish particulars.” That seems to be what gives her the edge and enables her to stand up to the world.

That comes from having been around awhile. You’re not foolish anymore.

I think part of a novel’s job is to insist that no human act or emotion is impossible. And by acknowledging some of the less presentable human acts and emotions you’re offering in your own way a kind of forgiveness.”

You teach creative writing at Yale, and Bookanista attracts readers who are on similar courses. What tips would you give them?

The only thing I have that even resembles advice for writers is: Don’t Panic! I went to school with a group of other aspiring writers and it wasn’t that I was the star and they were my acolytes. They were probably more talented than I was, but I was the one who’d sit in the chair, and sit in the chair, and sit in the chair, and rewrite the sentence 50 times until it came to some kind of life and I do feel that if you’re not willing to spend 10 hours writing a sentence, don’t waste my time with it.

Malcolm Gladwell determined that 10,000 hours is what it takes to become a genius…

Yeah! It’s almost like a form of mild autism. In that you’re someone who will not let go. The question of how can a sentence be more alive.

Is that also down to the pursuit of perfectionism?

No, it’s because you’re fucked up! It’s a form of mental illness.

Is that what Tyler has?

Absolutely, and Barrett is the opposite. Barratt can’t concentrate on anything; Tyler can only concentrate on one thing. I think it’s something perverse in some human’s natures. If you are sufficiently gifted and people have been telling you since as far as you can remember – you’re special; you’re going to do something major in the world – some people feel like: you know what? What if I don’t want to?

Why did you choose to set The Snow Queen between 2004 and 2008?

You know, some of these choices are a little intuitive. I was interested in the relatively short period during which Americans – a small, debatable minority – re-elected the worst president in history. A lot of us sat in front of our televisions and said: This can’t be happening, no, no, he destroyed the economy and annihilated a country that had nothing to do with 9/11. And as a country we said, Let’s have another four years of that, and it broke something in me. It tore some membrane that I hadn’t even known I had. I had no faith in the American people any longer. I think the Americans are capable of anything – most people are, I’m sure the English are too – but really watching these people, having been through four years of that, saying let’s have another four years of that, I just thought: I give up. I don’t know who you are.

George Bush was stupid. George Bush was invented. George Bush was a privileged blue-blood that we packaged as a Texas rancher. George Bush was not a smart man. Americans prefer leaders who are stupider than they are because it makes us feel better about our own shitty little life. It’s depressing. (Do you see how much I am like Tyler?) But then, not long afterward they elected an African-American president with real intelligence.

And that restored the faith?

Yeah – until the drones started blowing up wedding parties. It restored hope until it all started falling apart. Until he hired the people who destroyed the economy to fix the economy; until he changed his mind about closing down Guantanamo. Under his administration there are more rather than fewer drones blowing up people who have the temerity to be on the street at any given time. That has not been what we thought was going to happen. But for America, a deeply racist country, for Americans to elect an African-American president at that moment… it’s still a big deal.

OK, we’ve done the politics, now religion… Barratt’s spirituality comes through, he ‘sees the light’, enters a church. Is he in a weird place?

I wasn’t sure where that was going to go but I felt pretty clear early on it wasn’t going lead to an answer. What is important to me about Barratt and that vision is that a very traditional Catholic annunciation usually involves a very large Christmas ornament appearing in your living room telling you what to do. But what if the apparition had no advice at all? What if it left no instructions? What do you do now? Barratt is basically waiting to be told what to do: OK, you’ve shown me there’s something beyond human: What do you want me to do about it?

Is he looking for reassurance about life after…

Barratt is a regular secular guy, he never thought about anything like this at all. What was interesting to me about Barratt was, what if a visitation was offered to somebody who doesn’t believe in any of that? You know, who doesn’t think about that? He’s thinking about his boyfriend, who’s even dumber than George Bush. He’s not thinking about life after death. And then this thing happens. It was important to me that he’s intelligent, someone to take seriously, but not especially profound.

But he’s asking the questions a lot of people ask, especially when confronted by the possibility of loss…

I think never more so than in the 21st century. On the one hand a lot of us have some sense of perception of patterns and a power in the world that’s more than just randomness, and at the same time organised religion will destroy the world. That’s a problem. That’s a conundrum. At the same time religious fanatics are our worst enemies. So we’re in a funny position right now. We have the urge to have some kind of belief, but talk to somebody who professes to have belief and you realise you’re the dangerous motherfucker, you should be in jail. The drug dealers should be out of jail and you should be in jail.

One of the things this woman said to me when she was in a period of remission, she said: I know how fucked-up this is, but I’ve gotten so used to being the sick girl that I’m not sure how I would live as someone who’s healthy. Which is kind of intuitive.”

Beth haunts the novel. She’s the dying love of Tyler’s life. When she takes a walk on her own she has a profound feeling of insufficiency, that feeling of needing to give back more than she knows what to give back as thanks for being alive.

A lot of the characters I write are invented, but I wouldn’t have written a character like that if I didn’t know a woman like that. A woman that young with Stage 4 cancer is so potentially sentimental that if I didn’t know somebody, if I didn’t have access to what that experience is like, I wouldn’t try to do it. Cancer is, as in the novel, incredibly unpredictable. It looks like it’s gone away but then it hasn’t gone away. One of the things this woman said to me when she was in a period of remission, she said: I know how fucked-up this is, but I’ve gotten so used to being the sick girl that I’m not sure how I would live as someone who’s healthy. Which is kind of intuitive. It should be the best news in the world: now you will live like no one else has known how to live. Which is what she wants, but there’s also this fear, this sense that she’s learned how to be mortally ill. And that has become who she is.

The jigsaw fits neatly with Tyler because he doesn’t know how to live with a woman who is now well again. Without talking to each other about it they end up replicating each other’s feelings.

That turns out to be the problem. She’s literally resurrected, the best thing that could possibly happen, yet both of them have mixed feelings about it.

He even confesses to Liz that if the devil came by he would have to admit that he cared more about writing a song for Beth than for Beth herself.

I think part of a novel’s job is to insist that no human act or emotion is impossible. And by acknowledging some of the less presentable human acts and emotions – like for Tyler it mattered more to him to be the guy who wrote the song than Beth herself mattered – you’re offering in your own way a kind of forgiveness. From Madame Bovary on up, the novel is there to insist there’s not much of which humans are incapable. And being human and being capable of all things, there’s not much for which we can’t be forgiven.

And then later comes a twist and I won’t reveal, but Wow… I didn’t see that coming!

Every novel is also a mystery story. The model for all fiction is the detective story. In a murder mystery for example you want to surprise the reader, but you have to surprise the reader with something that’s been there all along.

Michael Cunningham was raised in Los Angeles and now lives in New York. He is the author of the novels A Home at the End of the World, Flesh and Blood, The Hours (winner of the Pen/Faulkner Award & Pulitzer Prize), Specimen Days, and By Nightfall, as well as the non-fiction book, Land’s End: A Walk in Provincetown. He lectures at Yale in English and creative writing. The Snow Queen is published by Fourth Estate in hardback and eBook.

Michael Cunningham was raised in Los Angeles and now lives in New York. He is the author of the novels A Home at the End of the World, Flesh and Blood, The Hours (winner of the Pen/Faulkner Award & Pulitzer Prize), Specimen Days, and By Nightfall, as well as the non-fiction book, Land’s End: A Walk in Provincetown. He lectures at Yale in English and creative writing. The Snow Queen is published by Fourth Estate in hardback and eBook.

Read more

Michael Cunningham at Yale

Farhana Gani is a founding editor of Bookanista. Follow her on Twitter: @farhanagani11