Through a mirror darkly

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“A fresh, accessible take on a great story.” Lionel Shriver

Well before Shakespeare made the feeling into one of the most celebrated tenets of art as well as life, the Greeks had already been there and done that. The principle of “all the world’s a stage” was for them the clearest, most perfect prism through which to analyse the full, multi-hued spectrum of human experience, perception and emotion, converge the vision on both mortal and metaphysical reality, and forge a society that looked closely at their fellow citizens on stage in order to recognise and understand, rather than watch as amused (or bemused) spectators who merely need to diffuse tension, throw care to the wind and escape a world that is (as much as it is not) of their own making. The Greeks used the material distance of myth and the stage to achieve the closest proximity to the human psyche, their contemporary society, and to existential concerns that transcended their lifetimes.

We still feel, at our most genuine and sincere, often at our darkest and most despairing, the compulsion to hearken back to the Greeks, and especially their tragedies, as we seek balance, a way to confront or reconcile our own different, yet so very similar existence. Virginia Woolf perhaps voiced this impulse with the finest economy and urgency: “It is not because we can analyse [the Greek texts] into feelings that they impress us. In six pages of Proust we can find more complicated and varied emotions than in the whole of the Electra. But in the Electra or in the Antigone we are impressed by something different, by something perhaps more impressive… In spite of the labour and the difficulty it is this that draws us back to the Greeks; the stable, the permanent, the original human being is to be found there.” Woolf saw in the Greeks the gesture of simple sincerity that is indispensable to the act of feeling, communicating, coexisting – the stability and permanence she evokes reflect the essentiality of human nature, and not merely a set of stabilising rules or abstract constructs. The labour and the effort, she also seems to say, are part and parcel of the gain.

Tragedy for the Greeks was a way of experiencing life in its most distilled, penetrating, and uncompromisingly raw state: it was a gesture of community as well as of introspection and of individual responsibility. Aristotle’s analysis in the Poetics is so much more than the definition of a literary genre: it is an entire ethics of existence and of co-existence, of seeing and reflecting, and especially of acting and of being. He gave us a model not of perfection, but of understanding and empathy, of pain and sympathy, of devastation and survival.

Greek tragedians did not seek to create excitingly original storylines, or engage directly in readily available political or domestic drama. They were quite happy to tap into familiar pools of narrative.”

From the numerous tragedians, few survive today even as names – a terrible loss of so many of the thirteen ways of looking at the blackbird that is our life, as Wallace Stevens might have lamented. Three (or perhaps five) however of Athens’ finest tragic playwrights have left us invaluable, indelible echoes of their voices, and certainly three different weights for the scale of all that is our humanity: Aeschylus (together, it is claimed, with his son Euphorion) projected on the stage a vision that was larger than life, an almost godly aspiration; Sophocles, on the other hand, sought to reveal to us things as they should be, extending an ethical challenge and moral invitation; while Euripides is perhaps the world’s first realist or pragmatist – his plays never shirk away from things just as they are.

Oedipus Separating from Jocasta by Alexandre Cabanel (1843). Stephen Gjertson Galleries/Wikimedia Commons

Greek tragedians did not aim for thematic fireworks – they did not seek to create excitingly original storylines, they certainly did not engage directly in readily available political or domestic drama. They were quite happy to tap into familiar pools of narrative, flex the collective tradition, cast it and reshape it in their hands, but always keeping the pools themselves untainted so they could return to them again for new, different inspiration. The thematic cycles were like kaleidoscopes – each turn providing a different perspective, image, collage of destinies and predicaments. Yet as in Wallace Stevens’ poem, the main chips of the image remained the same: the blackbird, whether before or after, is always part of the picture.

One of the most fecund series of stories was the Theban cycle that told the saga of Cadmus and his children. Branches stretched far enough to link up with other tantalising storylines, such as the Trojan epic cycle and its aftermath, or the Argonauts, Theseus or the anarchic new religion of Dionysus. They also resolutely made their way into history and politics, issues of social and gender equality, ethics of law and justice, the disputed territories of the human and the divine. Sophocles is our main source for the particular chapter of Oedipus and his family, with two surviving plays by Aeschylus and Euripides shedding light on the fratricidal clash between Oedipus’ two sons, set to rule Thebes after him. Bits and bobs of myth and lore have also come down to us in Homer, Hesiod, Pausanias and Statius, Ovid, Virgil and Seneca and in the meagre scholia that refer to the Oedipodeia. Whatever the case, this is what we have, and the horde is rich indeed. The wealth of human observation, of philosophical and socio-political enquiry, of literary beauty and of superb dramatic economy is more than sufficient for an infinite number of narrative epigones, and many have indeed followed Sophocles’ way. Each of these later literary lives seeks to renew the probe into fate and personal responsibility, authority and free will, crime and punishment, love and disdain, human and divine right and justice. Human hope and happiness.

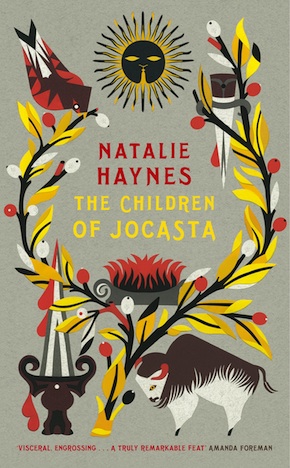

One of the most recent is Natalie Haynes’ The Children of Jocasta. Haynes is not unacquainted with the Greeks. She has a degree in Classics from Cambridge, and she has made the Greeks her company for quite a while now. She has pleaded for them, written, bantered, joked about them repeatedly, exuberantly, indomitably. It would be fair to say that Sophocles is perhaps one of her favourite Greeks – his Antigone is the play within the human play of her first novel, Amber Fire, where a progressive workshop on the Greeks and their tragedy, their sense of the miraculous and their propensity for transgression, is meant to act as the catalyst for a group of troubled youths and their teacher. In The Children of Jocasta the working brief has an enlightened, annalist slant: echoing historical revisionism, Haynes makes it her task to tell the story of the two characters literature has seemingly cast in the shadows of oblivion, Jocasta and Ismene.

Haynes takes tremendous delight in mapping out streets, public fountains and gardens, palaces and mere shacks… She feels a natural affinity to people and events.”

In an afterword to the novel, Haynes expands eloquently and passionately on what inspired and motivated her, and the sheer scope of the creative enterprise is highly impressive. It is irresistibly enticing to think there is another volume to be added to the unforgettable story of Oedipus, and the collapsing of time and genealogy, of reason and unreason, of vision and blindness, of mere humanity and human wonder that is his legacy. Haynes conjures up a remarkably tactile picture of the city of Thebes during Jocasta’s marriage to Laius, while Oedipus was her consort, and during the collapse of that very precarious vision of civic and domestic harmony. She manages to include the deadly strife between Polyneices and Eteocles, and even Creon’s succession to the helm. Although there is a tendency to orientalise (spicy chickpeas and flatbread are apparently the full extent of Theban diet) and to extrapolate sometimes at the risk of anachronism (glass-covered mirrors did not exist until the 1st century AD and it is unlikely the ancients used lime to prevent contamination from the plague), Haynes has evidently taken tremendous delight in mapping out streets, public fountains and gardens, palaces and mere shacks, opulent neighbourhoods and rundown boroughs. She feels a natural affinity to people and events, displays a proud sense of place, an acute ear for echoes and a thrill for authentic terminology.

Her finest moments are the dramatisation of the plague that will bring about Oedipus’ downfall. Haynes is tinglingly crepuscular, appropriately atmospheric and darkly broody in these moments, richly imaginative, almost forensic in her detail. She is drawing lavishly and evocatively from Thucydides’ haunting and detailed account of the Athenian plague of 430 BC, which recurred twice two or three years later, with catastrophic results for the city and its people. Sophocles’ plays too reflect the doom brought about by the epidemic, in real terms of human loss and suffering, but especially in terms of political stability, the public sense of security, the overarching feeling of doubt and questioning of law and society that ensued.

Mavie Hörbiger as Ismene in the 2015 Burgtheater Vienna production of Antigone. Christian Michelides/Burgtheater/Wikimedia Commons

Haynes’ writing is characterised by a dense inwardness, a compact narrative fabric as though each ‘perspective’ demanded to be total and absolute. Hers is a carefully worked text, at times too minutely detailed, awkwardly rich, sometimes laboured. Her psychological portraits tend to rely on earnestness and intensity, a touch of Janes Brodie and Eyre fused together, rather than economical exposition, and on assumptions that occasionally overload the dice. Her treatment of the characters’ names is unnecessarily disconcerting, with Antigone becoming Ani, Ismene Isy, Eteocles Eteo and Polyneices Polyn. Haemon is a rather uncomfortable Haem and Eurydice, his mother and Creon’s wife, an ungainly Eury.

Yet it is her treatment of the plot, of the strands of narrative that she pulls together, that is the spectacular centre of this novel. Haynes uses ‘perspective alteration’ to cast Jocasta and Ismene as the two poles of her Theban world. Like the original plan for an alternating reign of the two brothers, mother and daughter (and so much more) hand over the narrative baton to each other in this relay race between past and present – and a new, quite unexpected future. In the process, much is revealed (Laius’ predilections, which are part of the myth via his abduction of Chrysippus) and more is obscured. Antigone recedes in a corner as a rather entitled, self-absorbed, exquisite creature, Oedipus is cast as a regal consort with a horticultural passion, Tiresias disappears absolutely, or is glimpsed at, according to Haynes, in the somewhat sinister character of Teresa, Laius’ housekeeper.

Quite ingeniously, the Sphinx is no monster but a gang of brigands, throttling reckless travellers (the word Sphinx was presumed to derive from the verb to constrict, as in a vice). This demythologisation unfortunately comes at the cost of the famous riddle, the enigma that makes Sophocles’ play so eternally brilliant. Jocasta is angry more than she is regal, full of a discontented sadness as well as a new female voice. She is the fuller of the characters in the novel, even if Ismene-Isy gets to have the most (and cleverest) lines. As for Ismene, she is a bookworm, a bluestocking and the judicious and diplomatic rebel Antigone is not allowed to be. Fretting in women’s clothes, she is either poring over a papyrus, or lying bloodied after an attempt against her life, scampering down rocks, shovel in hand, to bury a brother. Haynes gives her readers generous servings of suspense, reversals of fortune, adventure, intrigue, palace plots and dark designs on power and immortality. She especially thwarts any presumption that all (or anything at all) is known ahead of time.

As sisters and princesses, Antigone and Ismene are simultaneously privileged and challenged by ethical demands, and this questioning of the entitlement to and duty towards privilege is part of the unique power of the story cycle.”

On its own merit as a novel with no referential past, The Children of Jocasta is an unusual, sustained read, even though it would benefit from more economy, a finer calibration of the elements, especially a more allusive treatment of both character and situation. There is a waft of Victorian embellishment at times that halts the rhythm and the pace, and takes away from the thrill of its innovation. As a story seeking to be added to a greater tradition, The Children of Jocasta often seems to squabble too much for attention. There are too many easy narrative peaks, Creon emerges as a Richard III character, and, aside from what Haynes calls playing “extremely fast and loose with their story… and [being] equally cavalier with archaeology”, what we particularly miss is the complex problematisation, the hued characterisation and thorny involvement in the characters’ psychology and ethics. We feel deprived of the tragic side of what Yeats called the “triumph of intellect”, or the mystery and pain of Oedipus’ words towards the end of Oedipus at Colonus: “so when I cease to be, then my worth as a man begins.” We long, especially, for the mirror-in-the-mirror images of trauma and drama, as Creon must face the suicide of Eurydice just as Oedipus had to confront the death of Jocasta (Haynes has a different end in store for Eury). As sisters and princesses, Antigone and Ismene are simultaneously privileged and challenged by ethical demands, and this questioning of the entitlement to and duty towards privilege is part of the unique power of the story cycle. Where are the people of Thebes, so crucially visible in their vital importance and human triviality on the Athenian stage as the Chorus? Here they have become a mere offensive, uncomprehending rabble, a pitiful and pitiless kind of mob.

The Theban plays provided a starting point for the Athenians to discuss their polis and their politics, to debate about ethics, right and wrong and justice, about who is human and who or what is divine, to contemplate good and evil, pleasure and hubris. They provided an occasion to lament the wasting of life, to dream of the possibility of a ‘what if?’ happiness. Engaging with ancient writers and texts is above all a humanistic enquiry, empathically attuned to the beauty and the suffering that is human existence. At the end of The Children of Jocasta, even if dazzled by the countless tours de force, we are still left seeking that special kind of beauty and tragic balance afforded by the more elliptical, yet somehow more fulsome tragedians.

Natalie Haynes is a writer and broadcaster. She is the author of The Amber Fury, which was shortlisted for the Scottish Crime Book of the Year award, and The Ancient Guide to Modern Life. She has written and presented two series of the BBC Radio 4 show Natalie Haynes Stands Up for the Classics. In 2015, she was awarded the Classical Association Prize for her work in bringing Classics to a wider audience. The Children of Jocasta is published by Mantle in hardback and eBook. Read more.

Natalie Haynes is a writer and broadcaster. She is the author of The Amber Fury, which was shortlisted for the Scottish Crime Book of the Year award, and The Ancient Guide to Modern Life. She has written and presented two series of the BBC Radio 4 show Natalie Haynes Stands Up for the Classics. In 2015, she was awarded the Classical Association Prize for her work in bringing Classics to a wider audience. The Children of Jocasta is published by Mantle in hardback and eBook. Read more.

nataliehaynes.com

Author portrait © Dan Mersh

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.