The opposite of Birmingham

by Ian NairnParis is a collective masterpiece, perhaps the greatest in the world. Yet it is not a place for individual wonders, and many visitors may feel the kind of disappointment that I did on my first visit: of the world-famous attractions only the Eiffel Tower, the Opéra and the Louvre colonnade really live up to their reputation. But sooner or later, travelling from one piece of architecture to another, something quite different may catch your eye: a café, a public park, maybe nothing more than the gestures of a gendarme directing traffic. Then the magic will begin to work and may not stop until you are drunk with a hundred patches of gravel and a thousand expressive shrugs.

You need no Champs-Élysées or Versailles to make you feel rich or kingly: Belleville or the Parc Montsouris will do just the name. Fixed out of time, and hence immortal, each action carries its total weight, precise and lucid; this is why most topographers end up, like this one, speaking a parody of Jean Cocteau.

The words in the songs about springtime in Paris are absolutely true – and it is a memorable experience to have banality transform itself into ideal as you sit and look, hear, smell, and taste – the whole city is urging you to greater depth of feeling, the opposite effect of a Birmingham. Tragic feeling, maybe: there is no guarantee of happiness here. But you are likely to leave more alive than when you arrived.

Click on images below to enlarge and view in slideshow

Jardin des Tuileries

The eastern end, next to the Louvre, is a mini-Versailles of formal planting; the western end, next to the Place de la Concorde, one of the most soothing places on earth. Nowhere else in Paris is the city’s uniqueness presented with such conviction. Because this end of the gardens is, simply, a gravelled space interrupted occasionally with grass and thickly planted with trees in a formal pattern. What’s special about that? The scale and compassion of the gesture, which supplies basic amenity as though it were food and drink and then leaves you free – really free – to enjoy it. These are enchanted groves for world-citizens, where each gesture has its own weight and space: absolute, unimpeded by any outside influence: assessed by its own nature and no other – whether it is a kiss or a system of philosophy. This apparent innocence is in fact the product of complete sophistication, the far end of experience where everything is real and new yet full of illusion and continually remembered. Not bad for a thick copse and some gravel; but that’s Paris.

The final justification of the gilded acres of Versailles and Fontainebleau… Pay any price and go and see anything, however unsuitable: the experience will be worth it.”

L’Opéra

Charles Garnier, 1860–75

Quite rightly just l’Opéra, not a name like Covent Garden or La Scala. This is the final justification of the gilded acres of Versailles and Fontainebleau: a declamatory roulade of allegory that would pump a sense of occasion into the limpest libretto. The outside gives clear warning of what is about to happen, but it is only tuning up; overture, grand march, love duet, and final chorus are all inside, in the gorgeous sequence of double staircase leading to the auditorium on one side and a third-floor foyer – what a name for it! – on the other, immediately behind the façade. This is more operatic than the opera, pulling the audience willy-nilly into grandeur. There is no longer a cast and spectators, there are various persons assisting at a rite, some singing and some listening. To hear Offenbach in these surroundings must be unforgettable. La Belle Hélène is the building, just as Messiah is the Albert Hall. The Opéra has consumed itself – when you buy a programme, you get as it were a sliver of goddess – and architecture has no higher function. Pay any price and go and see anything, however unsuitable: the experience will be worth it.

Passage du Caire

The entry from the Place du Caire is modest enough, a mild Egyptian joke. But ‘passage’ is an understatement: this is a whole slice of the city under glass, with cross avenues, side turnings and half a dozen separate exits. The scale is tiny and it feels like nothing so much as one of those old streets re-assembled in go-ahead museums. I saw it on a Sunday morning and then, with nobody about and the smallest sounds reverberating in the pin-drop silence, it is a very eerie place indeed.

Saint-Eustache

A great and noble building wearing some mighty funny clothes. In all but length it is as big as Nôtre-Dame; but it was begun in 1532 and consecrated in 1637. So the style is the French Renaissance at its fussiest. Small orders clamber up huge piers on each others’ shoulders; every corner is filled with some kind of fretwork, topped up with ill-advised transcriptions from the Gothic. Yet the space and scale conquer everything and even turn it into a kind of mason’s holiday from the long-prescribed Gothic details. This is the rich expression of a rich, proud and free parish – and, ironically, as Protestant as anything in Holland. Les Halles is the perfect neighbour for it. The organ has been famous for centuries, and no wonder. When it is playing the whole building seems to be inhabited by music, scraping out the ornate vaults, peering into the galleries. The detail feels like so much musical notation written on the walls; and, acoustically speaking, I suppose it may be.

Two of the furnishings are worth a special look. The banc d’orgues in the nave opposite the pulpit was given in 1720. It is a superbly designed bit of saturnine elegance – thick curves and elongated angels’ legs in wicked counterpoint. And Colbert’s tomb by Coysevox (1685–7; chapel next to the apse, on the north side) is for once free of allegory and arrogance: a humble human being kneeling in rich clothes and hoping to be forgiven.

Place des Vosges

A formal effect stranded like a whale in the bustling Marais. Melancholy and at odds, the Place des Vosges remains a monument to inspect rather than part of the life of the city. Begun in 1605, the constricted entrances from north and south emphasize its alien nature. It should be a teeming square like Salamanca: instead there are trees which blot out the view of the other side, a public park, children playing – the right thing in the wrong place. The elevations, by themselves, are ordinary, and life subsists in the long arcades, ready-made for a murder or a hanging, the body lazily swinging in and out of the view. The Place des Vosges swings lazily into the history books – as one of the first formal squares in northern Europe with the façades conforming to an overall design – and out again.

3 rue Volta

‘The oldest house in X’ is usually an invitation to see some over-pickled nonentity. No. 3 rue Volta, venerable and half-timbered, is not at all like that.

Shabby, thumbed over, barely recognizable, but still supported by teeming life. Here and in the rue au Maire there is a fragment of old medieval Paris or present-day Naples: narrow streets, piling together of people and uses – a memorable hard-bitten croak. I hope the rue Volta never goes up in the world; demolition would be better than politeness.

Rue Berton, Passy

‘Si curieuse,’ says Michelin, and it certainly is. It runs along the slope, halfway up from the river to the main boulevard of this pleasant, well-heeled and unremarkable western suburb of Paris. It has slipped through the urban mesh, and keeps a fierce private character – small houses, high walls, and a narrow, cobbled surface. It is only a few yards long, but the illusion of a secretive provincial town is complete – a tantalizing reminder of how all kinds of different characters could be preserved intact in the middle of a big city.

The Sacré-Coeur has earned its keep before the visitor even gets within a mile of it. It is just as well, for the outside seems a crazily perverse insistence on sending the ghost of Périgueux Cathedral to a 19th-century École Normale.”

Western approach to Paris from Neuilly; Arc de Triomphe

Arch: Chalgrin, built 1806–36

This really is the way to announce a city. Down from the Rondpoint de la Défense at Puteaux to the Seine, up again through Neuilly, inexorably steady, tree-lined, straight at the Arc de Triomphe, down the Champs-Élysées at the same gradient, back to the river at the Place de la Concorde. No variation or deviation whatsoever, the one occasion when it is absolutely right. London could do with one – just one – entrance like this. What in fact happens in Paris is that the Arc de Triomphe has nine more avenues radiating from it… but that does not diminish the magnificence of this one.

The arch is indeed a triumph. It is on the exact high-point, an upturned saucer, so that the surrounding buildings and trees are always lower. Only the Eiffel Tower breaks through and that in a friendly, undomineering way. The arch may have

Roman models, but it feels French to its fingertips, the inimitable combination of huge size and human scale. Underneath, the Napoleonic battles form a bewildering Cook’s Tour for the nation which of all Western Europe is least inclined to that kind of travel: perhaps, since Napoleon went on his travels, the rest of the nation has ceased to want to, like our own Charles II. Only in the sculpture do the aspirations become tangible and distasteful. Cortot’s crowning of a simpering Napoleon on the east side is no more than a joke; Rude’s famous ‘La Marseillaise’ is more dangerous because better done, the incipient hysteria almost convincing. Here is the unexpected grandma of Wagnerian over-emphasis.

Sacré-Coeur

Abadie, 1874 onwards

By what it does to the skyline, the Sacré-Coeur has earned its keep before the visitor even gets within a mile of it. It is just as well, for the outside seems a crazily perverse insistence on sending the ghost of Périgueux Cathedral to a nineteenth-century École Normale. Inside it improves again. Abadie could clearly organize spaces (or repeat 700-year-old organizations) very well, and the corners of the Sacré-Coeur have the same kind of cavernous honesty as the undecorated parts of Westminster Cathedral. But what a waste of talent it all was – nowhere more than in the crypt, where Abadie could have spared us his holiday snaps of a journey in the Dordogne – and what a lot of time we have had to throw away in trying to sort it all out. We are nowhere near the end of the unravelling yet.

Tour Eiffel

Gustave Eiffel, 1887–9

It must represent Paris for millions; and it is a well-deserved piece of luck that the Eiffel Tower is very good as well as very tall. Eiffel conceived it with true nineteenth-century gusto – ‘France will be the only country to have a flagstaff three hundred metres high’ – but also with nineteenth-century civility, comprehending and compassionate. Never for a minute does the tower bear down on the city or its visitors; never does it endorse the puniness of man.

Instead, it enlarges the viewer, gathers him up in its colossal size (Nôtre-Dame could be fitted in diagonally between the four corner pillars) and declares that the sky is not terrifying at all but was meant for our enjoyment along with Pernod and Coquilles Saint-Jacques. The bottom stage is like four railway viaducts on the slant; the ascent, with all the changes and queuing, is a vertical Métro journey. The crowded lifts become an involuntary U.N.O., and because everyone has come simply to look at the view, it is one of the most cheerful of Parisian attractions. At the first level there are simply rooftops; it is the second which is the key. As from Montmartre, all of the major monuments stand out as they ought to; the Panthéon, Invalides and Saint-Sulpice very proud, and the Arc de Triomphe revealed in its true size (on the ground it seems diminished by the vast rond-point and the whirling traffic). There is no better place to absorb all this in tranquillity than the bar. The third stage doesn’t add very much, and in fact diminishes the formidable profile of Paris. But what it has got is a delicious kind of V.I.P. lounge, done out with full fin-de-siècle pomp and apparently not touched since. It would be quite a place for an assignation.

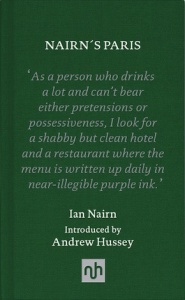

This is an edited extract from Nairn’s Paris (Penguin Books, 1968), now reissued by Notting Hill Editions.

Nairn’s emergence as a maverick, inspiring figure in mid-twentieth century architectural writing (and broadcasting) was sudden, and his claim on the public’s attention all too brief.’ Gillian Darley, AA Files

Ian Douglas Nairn (1930–1983) was a British architectural critic and topographer. He coined the term ‘subtopia’ for the areas around cities that had in his view been failed by urban planning, losing their individuality and spirit of place. In the 1960s, he contributed to the volumes on Surrey and Sussex in Nikolaus Pevsner’s ‘Buildings of England’ series, and published Nairn’s London and Nairn’s Paris as well as presenting several BBC TV series. His work has influenced writers as diverse as J.G. Ballard, Will Self, Iain Sinclair and Patrick Wright. Nairn’s Paris is published as a cloth-bound pocket hardback by Notting Hill Editions, with a new introduction by cultural historian Andrew Hussey.

Ian Douglas Nairn (1930–1983) was a British architectural critic and topographer. He coined the term ‘subtopia’ for the areas around cities that had in his view been failed by urban planning, losing their individuality and spirit of place. In the 1960s, he contributed to the volumes on Surrey and Sussex in Nikolaus Pevsner’s ‘Buildings of England’ series, and published Nairn’s London and Nairn’s Paris as well as presenting several BBC TV series. His work has influenced writers as diverse as J.G. Ballard, Will Self, Iain Sinclair and Patrick Wright. Nairn’s Paris is published as a cloth-bound pocket hardback by Notting Hill Editions, with a new introduction by cultural historian Andrew Hussey.

Read more.