Not alone

by Lily Bailey

“An intsnse heart-rending rollercoaster of a book.” HuffPostUK

In the playground, fads come and go consistently, without apparent supervision, like waves on a beach. We had Pokémon, we had Furbies; we had aliens encased in strange plastic eggs. Then at some point, when we were five, imaginary friends took off as a craze. People would save spaces at the lunch table for someone no one else could see. Girls would sit on the climbing frame, plaiting hair that looked like air to those without an imagination.

No one wanted to be that – a child without an imagination. It made you no fun to play with. It meant you got excluded from certain games. Some of those who said they had imaginary friends didn’t really have any specific vision of what this friend might be like, nor did they really care for the craze at all. Desperately dull girls like Claudia couldn’t even make up a good story when playing with a doll’s house; how could they conjure up a whole person?

Some of the die-hard fans, the revolutionaries with sparky minds and endless originality, may have taken their imaginary friends home for dinner, shared a bath with them, and read them bedtime stories. But the majority were probably scattered somewhere between the two extremes. They could imagine something, if not necessarily a fully formed person, but when school ended, that was that. The friend was left behind at the gates, without a thought, until the next morning, when the craze demanded that she reappear. That was why this fad was terrifying; amid a constant onslaught of daily change and childhood adaptation, one thing had stayed weirdly constant in my life. For as long as I could remember, I wasn’t me, I was we.

Two of us sat side by side in my head, woven together, inseparable. She didn’t even have a name; she was just She. Really, it was hard to say where She ended and I began. But food was not shared with her. She did not play tag and never required a seat. She was, by her very essence, nothing like these imaginary friends. She was just there.

A fad demands that something that wasn’t there before come into existence; and that meant only one thing. Normal children didn’t have two people in their heads.”

One was not proud of her, in the same way as one is not proud of a liver, and there was no need to show her off, nor tell anyone She existed.

But though her differences were concerning (why did other kids insist on parading their friends around? Were they just for show? Couldn’t they see it didn’t have to be a competition?), they were nothing compared to the fad’s main implication. Because a fad demands that something that wasn’t there before come into existence; and that meant only one thing. Normal children didn’t have two people in their heads.

Which meant I must be very different, for mine was not the sort of friend to be left behind at the gates.

***

I’m standing outside the support group room with my mum.

I peek in through the door’s glass window. I see a huge circle of people sitting on plastic chairs.

“I’ve changed my mind, Mum. I don’t want to go.”

“Come on, we’ve come all this way – just go in for a little bit and see how you find it. I’ll be right by you.”

“I don’t want to. I really, really don’t want to.”

I peek in again. I see a woman with long brown hair talking, but I can’t hear what she is saying. She is making lots of gestures.

Mum opens the door and pushes me in. I let out a loud squeak. About thirty heads turn to look at me.

“Welcome! Have a seat,” says a man sitting in the corner of the room. “We’re doing introductions. So you just have to say your name, your experience of OCD, and how your week has been. And you’re welcome to pass if you would prefer not to say anything.”

I sit next to Mum on the other side of the circle. Each person speaks for a minute or two. I pass when it gets to me, but Mum makes up for that.

“This is Lily, and I’m her mum. It’s our first time at a support group. Lily doesn’t really want to be here, but I’m hoping that it will be helpful for her. I’m here because I want to learn more about OCD and how I can help Lily. Hello, everyone!”

She gives a little wave.

“Welcome, both of you,” says the man again. He actually does sound quite welcoming.

It’s odd, because I always assumed that if I met a group of people with OCD, they’d all be sitting on newspapers to avoid contamination with the chairs, wearing gloves and perhaps surgical masks, tapping things repetitively.

But everyone here looks normal, and only a few of them have contamination fears.

I also thought there would be no point going to a group like this, because no one would have similar obsessions to me, but it seems that was wrong too.

“I always wanted to be a teacher, which I am,” says the girl opposite me. “But I ended up teaching adults, because I’m scared I’ll harm children if I’m around them.”

“I’ve had a really bad week because I feel like these thoughts are never going to stop,” says one guy.

Another says, “My OCD centres on preventing harm. So if I see anything in the street that could be hazardous, like glass or whatever, I have to do something about it. I’m always looking out for things that could cause harm so I can remove them. And I have some contamination problems. But I’ve had a really good week. I feel like I’m having a breakthrough with my CBT.”

“My OCD also revolves around stopping bad things happening,” says someone else. “Particularly to animals. Last week I saw a frog on the pavement so I tried to move him to a grassy knoll so he wouldn’t get trodden on.”

“I do that!” chips in a guy across the room. “I pick up snails and slugs from the pavement and rehome them. I also retrace my steps to make sure I haven’t trodden on one.”

“Anyway, so I pick this frog up, yeah – and he jumps out of my hand, right into the road. And then bam, right in front of me – squashed by a car.”

There’s a collective intake of breath as the group acknowledges the psychological implications of sod’s law conspiring against the frog Samaritan.

“Yeah,” he adds. “I was pretty upset.”

There are people like me. Others out there who spend their days caught in the peaks and troughs of endless thought. I am not a freak.”

Halfway through, people talk to each other during a fifteen-minute break. The man who welcomed us comes over to introduce himself as Thomas and asks how I am doing.

For the second half he calls for quiet.

Conversations fade out, and people who have moved around scurry back to their seats. Across the room, the woman who said that she crochets to keep herself focused on something other than her thoughts goes back to making an orange scarf.

“Our discussion topic today is guilt, how it affects us, and what we can do to overcome it.”

There’s a collective murmur of approval at the choice of topic.

“Oh god, don’t even get me started on guilt!” says someone. “I’ve got enough guilt on me to go round the whole of the UK prison system!”

Everyone laughs.

I feel like I have come home.

Later I lie in bed, feeling more comforted than I can ever remember feeling. There are people like me. Others out there who spend their days caught in the peaks and troughs of endless thought.

I am not a freak.

I roll over and put my arm around Rocky, who is curled up next to me. I breathe in the soft talcum-powder smell of his fur and listen to him snoring gently. I’m so glad I’m not alone anymore.

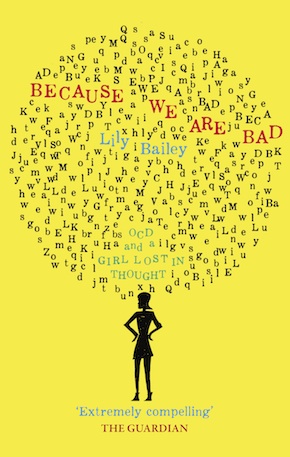

From Because We Are Bad (Canbury Press, £7.99)

Lily Bailey is a writer and model based in London. Because We Are Bad: OCD and a Girl Lost in Thought is published in paperback, eBook and audiobook by Canbury Press.

Lily Bailey is a writer and model based in London. Because We Are Bad: OCD and a Girl Lost in Thought is published in paperback, eBook and audiobook by Canbury Press.

Read more

lilybailey.co.uk

@LilyBaileyUK

Author portrait © Amy Shore