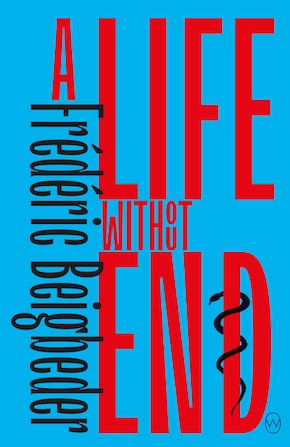

Deciding not to die

by Frédéric Beigbeder

“This mad philosophical and biological quest is a life-affirming and intelligent reflection on the meaning of life.” Psychologies

Increasingly frequently, when out in the street, I run into people I know, but when I go to kiss them I remember they’re dead and realize to my horror that I’m about to kiss a doppelganger. It’s pretty unsettling, having to stop yourself saying hello to the dead.

“Hi Régine!”

“Excuse me?”

“You’re… you’re not Régine Desforges?”

“No.”

“Oh fuck, I’ve just remembered, she died three years ago…”

“It’s obviously not me.”

“Are you often mistaken for her?”

“Sometimes – it’s my red hair. People also mistake me for Sonia Rykiel…”

“She’s dead too! Does it bother you, being the spitting image of all these dead redheads?”

“Does it bother you that you’re not as funny in real life as you are on TV?”

You have to hurry if you want to talk to the living. A worm lives for eighteen days, a mouse three years, a Frenchman seventy-eight. If I consume nothing but vegetables and water, I’ll add ten years to my life, but I’ll be so bored it will feel like a hundred. Maybe that’s the secret of eternal life: an ocean of tedium so vast it slows time itself. The statistics are unarguable: in France, in 2010, there were 15,000 people over the age of a hundred. By 2060, there are expected to be 200,000. I’d prefer to be a transhumanist superman to a vegan old-age pensioner: at least a transhumanist superman can gorge on saucisson and booze, provided he has his organs regularly replaced. All I want in life is for someone to repair me like a machine. I dream that in the future doctors will be called “human mechanics.”

I made an urgent appointment with Madame Enkidu, my psychoanalyst. I hadn’t seen her for ten years; she helped me deal with my cocaine addiction and get over my first two divorces. Her consulting room near the Place de l’Étoile was still painted magnolia, a box of Kleenex still lay in ambush on her desk. The box of tissues in a shrink’s consulting room is the modern-day equivalent of the sword of Damocles. There is no sofa in Doctor Enkidu’s office: she and her patients talk face to face. Then, face buried in Kleenex. Her bookshelves are full of psychoanalytic monographs with convoluted titles: theses on suffering, dissections of grief, cures for melancholy. Ring binders full of scientific articles dealing with the struggle against depression and suicide.

“When all’s said and done, psychoanalysis is just badly written Proust,” I said.

My psychiatrist nodded politely.

“It’s weird,” I added, “I’m paid to talk to millions of viewers, but you’re the only person who listens to me.”

“Because you pay me.”

“Anyway, the reason I’m here is that I’ve decided not to die.”

Spending all day listening to a torrent of human misery is clearly not the secret to eternal youth. When she saw me, she looked startled.”

Her pitying look had not changed either. She had a few more crow’s feet, the bags under her eyes were darker, her hair probably dyed. Spending all day listening to a torrent of human misery is clearly not the secret to eternal youth. When she saw me, she looked startled. I probably looked a lot older too. She never watched television; if she had, she wouldn’t have been surprised at the grey in my beard.

“Not dying is a wise decision.” Her eyes twinkled sardonically behind her half-moon glasses. “It makes a change, I have to say. Last time I saw you, you seemed intent on pursuing a very different goal.”

“I’ve never been more serious. I am not going to die, full stop.”

“And when did it occur to you, this resolution?”

“Oh… My daughter asked me if I was going to die. I didn’t have the courage to say yes. So I told her that, from now on, no one in our family is going to die. Does that make me a bad father?”

“A good father is one who worries that he’s a bad father.”

“That’s clever. Is it a quote from Freud?”

“No, it’s a quote from you. You said those words in 2007, probably to reassure yourself when you were cheating on her mother. At our very first session, you were already talking about your fear of getting old. It’s the Peter Pan Syndrome, very common among Western men in their forties. Fear of old age is a fear of death dressed up as latent hedonism.”

“I wasn’t aware hedonism was an illness. Pretty soon, our society is going to be locking Epicureans up in asylums. These days, pleasure in every conceivable form is punishable by law, while being promoted by advertising. It’s a paradox that produces millions of schizophrenics. You have capitalism to thank for that – without it, you might have to shut up shop.”

“Please, you’re not going to give me that middle-class libertarian spiel, are you? We’re not on TV. You can check: there’s no hidden cameras.”

These days, Dominique Strauss-Khan has made orgies seem sordid, and the word libertine conjures up images of doddery old men in stained kimonos, like Hugh Hefner.”

I suddenly remembered why I stopped coming to see this dour therapist: I hated her clear-sightedness. I’ve always been frightened by intelligent women, ever since my mother. But it was my fault: I’d just had a cardiac CT, and now it felt like I was having a brain scan. I felt like an archaic libertine in a world where hedonism was dismissed as the perversion of dirty old men. To think that, when I was young, people felt they had to at least pretend to be swingers if they wanted to be cool. We used to make up stories about things we’d done at Les Chandelles, the swanky Paris sex club. These days, Dominique Strauss-Khan has made orgies seem sordid, and the word libertine conjures up images of doddery old men in stained kimonos, like Hugh Hefner (also dead). We’re living in a time of extraordinary sexual regression. You might even call it the sexual counter-revolution.

“Doctor, cemeteries are full of corpses rotting in coffins while people dressed in black stand around, trying to focus on the grieving orphans and look sympathetic. A bunch of bastards who knit their brows to make it look like they’re concerned – I feel like punching them. I have no time for empathy, or for sympathy.”

“Death makes people vicious,” she said without smiling, just to justify her salary (€120 for a thirty-minute session). “When animals sense it, they sometimes become dangerous.”

“There must be some way to solve the problem.”

“Which problem?”

“Death. Mankind has always come up with a solution. We invented electricity, the internal combustion engine, radio, television, spaceships, vacuum cleaners that don’t lose suction… By the way, I had a dream that a vacuum cleaner hoovered up my parents’ ashes which had been tipped out onto the carpet. What would Lacan have made of that?”

“A typical case of morbid delirium, aggravated by paranoid narcissistic megalomania, exacerbated by celebrity and multiple-drug dependence. What I find interesting is you attempt to remarry your parents by mingling their ashes. Was it nice, seeing them reunited in your dream?”

“Listen, science is on the point of eradicating death, and I don’t want the discovery to come after they kick the bucket. You have to admit, it would be pretty shit to die just before science discovers immortality. We need to hold out until 2050 but, based on the average life expectancy of French men, I’m scheduled to die in 2043. I’m not asking for much, just to narrow this seven-year gap. Everyone in the world wants what I want. In my dream, it felt comforting, hoovering up death. It made death disappear. I woke up feeling great. You don’t want to die, do you?”

“I’m reconciled to accepting human mortality. I can’t say I find the prospect thrilling, but I’ve learned not to rail against things I can’t change.”

“In a minute you’ll be paraphrasing Montaigne: ‘To psychoanalyze is to learn to die.’ I don’t give a shit about philosophy, or about psychoanalysis. I don’t want to learn to die, I want deal with the problem. My time is limited: I’ve got twenty-six years to defer the final deadline. Oh, and I want my family to be immortal too. Personally, I think this should be the aim of every normal human being.”

“No, to be normal is to be mortal. The countdown started the day you were born. Accept it. You can control everything but that.”

“You don’t understand where I’m coming from. You think I’m Don Quixote while actually I’m James Bond. My death is a bomb set to explode, and I have to defuse it. To music by John Barry if necessary. I don’t care if you think I’m a control freak.”

Outside her window, cars honked their horns, revved their engines, spewed exhaust fumes into the street. That’s the real mystery of modern society: why do mortal individuals accept traffic jams on ring roads?”

Madame Enkidu looked at me sadly, the way you might look at a homeless person holding a hand out when you’ve got no small change. Outside her window, cars honked their horns, revved their engines, spewed exhaust fumes into the street. Down in those gridlocked cars, newly minted fiftysomethings were breathing in particulate matter while listening to air-pollution warnings on France Info every five minutes. You could hear them thinking, “Shit, it’s going to be at least another hour before I get to Porte Maillot, and I’ll die in two decades. On my deathbed, I’m going to regret spending this hour in a traffic jam breathing in poison.” That’s the real mystery of modern society: why do mortal individuals accept traffic jams on ring roads?

“What I’m saying is pretty simple,” I went on, “I belong to the last mortal generation, but I want to be part of the first immortal generation. My death is just a matter of timing.”

My therapist smiled as though I had just scored 100 on the Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale. She was probably considering having me sectioned and transferred to the nearest psychiatric unit. She’s used to listening to bullshit, but I’d gone too far; I was irritated to see her condescending sneer as she took notes for an upcoming book to be published by Odile Jacob. Eventually, she scribbled an address on her pad with her Montblanc, peeled off the page, and handed me the prescription.

“Okay, maybe I know someone who can help – but he’s in Jerusalem. He’s a researcher working on cell renewal. It’s worth a punt. If worst comes to worst, a vitamin cure wouldn’t hurt. Can I take a selfie with you? It’s for my niece. The stupid girl is a real fan of your show. She loved the episode where lockjaw stopped you being able to speak.”

A cloud shaped like an unknown country scudded across the sky. “Cell Renewal.” As I stepped out of the grey building it occurred to me that the crazy old bat might have put me on the right path. Having accepted her own impending death, she’d offered me a way to postpone mine. This didn’t stop me sobbing in front of a luxury travel-goods store that shall remain nameless, since I don’t want to give free advertising to Goyard. A passerby clapped me on the back and said, “Hey, you had me in stitches that time you threw up on TV! Can I get a selfie with you?” I dried my tears and posed, making the V-for-victory sign. The public always expect me to be hilarious and outrageous. They’re disappointed when they discover I’m shy and boring. Fans want to have a drink with me so they can tell their mates we got rat-arsed together. There was a point in my career when I did everything I could to live up to my reputation. I handed out drugs to strangers so they could tweet about it. I posed for shirtless selfies with a bottle in one hand and a baggie of white powder in the other. This was the night when I stopped burnishing my character as a trash-punk TV presenter, all I wanted was to be left in peace for the three centuries I had left to live.

From A Life Without End (World Editions, £12.99), translated by Frank Wynne

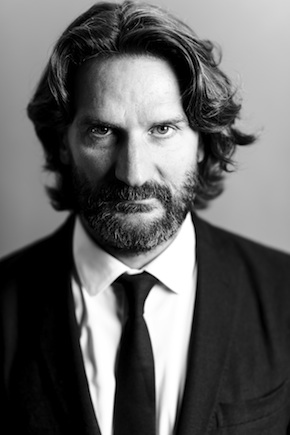

Frédéric Beigbeder is a French journalist and critic, and is responsible for the literary section of Le Figaro Magazine. Also a bestselling author, his novel 99 Francs both got him fired from his advertising job and established him as a controversial force within French literature. For his other novels, he has been awarded various prizes including the 2003 Prix Interallié and the 2009 Prix Renaudot and the 2005 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize for his novel Windows on the World. He is a regular guest on French national morning radio, and a frequent contributor to El País Icon (Spain), Interview (Germany) and Esquire (Russia). A Life Without End is published in paperback and eBook by World Editions.

Frédéric Beigbeder is a French journalist and critic, and is responsible for the literary section of Le Figaro Magazine. Also a bestselling author, his novel 99 Francs both got him fired from his advertising job and established him as a controversial force within French literature. For his other novels, he has been awarded various prizes including the 2003 Prix Interallié and the 2009 Prix Renaudot and the 2005 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize for his novel Windows on the World. He is a regular guest on French national morning radio, and a frequent contributor to El País Icon (Spain), Interview (Germany) and Esquire (Russia). A Life Without End is published in paperback and eBook by World Editions.

Read more

Buy from Book Depository

Author portrait © JF Paga/Grasset

Frank Wynne is a literary translator and writer. Born in Ireland, he moved to France in 1984 where he discovered a passion for language. He began translating literature in the late 1990s, and in 2001 decided to devote himself to this full-time. He has translated works by Michel Houellebecq, Ahmadou Kourouma, Boualem Sansal, Claude Lanzmann, Pierre Lemaitre, Tómas Eloy Martínez, Patrick Modiano and Almudena Grandes. His work has earned him awards including the Scott Moncrieff Prize and the Premio Valle Inclán. His translation of Vernon Subutex by Virginie Despentes was shortlisted for the Man Booker International 2018.

terribleman.com

@Terribleman