My one and only

by Marina Šur PuhlovskiHis parents leave on a five-day trip to Dubrovnik, his father’s home town, hurray, I mentally dance with joy, an empty apartment just for the two of us, to play at being married. I’ll have to sleep at home, though, because that’s only right, an unmarried girl can’t sleep at her boyfriend’s even though she’s already slept with him. Which my father knows, because he asked me and I told him, I don’t know how to lie, and it appears I’m brave to boot.

We’re sitting at the kitchen table when he asks me, both of us are serious, it’s a serious question, especially when asked by a father who doesn’t want yes for an answer, he can’t take yes for an answer, but he asks because he suspects it, because he’s upset. He smokes Herzegovina unfiltered, and he knows that I’m also a smoker because I lit my first cigarette in front of him, when I came of age, I saw it as my right. On the table is a raspberry soda, mixed, exceptionally, with two fingers of wine, because of the importance of the occasion, because otherwise he isn’t allowed, not even one finger of wine, because his liver is disintegrating. His eyes are a murky yellow, the pupils strangely dirty and his face already has a dark tone to it, as if he’s been in the sun, which he hasn’t, it’s dark because he’s sick; he’s half-bald and the little that’s left of his plastered down hair is grey, only his Hitlerite moustache is black, because he dyes it.

When he hears my answer, he immediately reaches for his glass, his face looking even deader than usual, which seems impossible until it happens, it literally collapses. And he’s breathing heavily, through his nose, in and out; he doesn’t say anything, but it’s hit him hard, to the very depths of his fatherhood. He shouldn’t have asked.

I can’t spend the night with the man I’ve already slept with, that would only confirm something that mustn’t be confirmed, it has to be covered up, denied, the exact opposite has to be proved, as if I had just been joking. Never mind, I think, the coming days are worth more than the nights, days when we’ll be alone from morning till night, something I’ve been dreaming of for a long time. The market, stalls with vegetables, yellow, red, orange, green and purple, you pick them carefully, I like wild lettuce, but his family eats butterhead lettuce, we’ll have to choose, and I like a salad of grated carrots, with garlic, which they don’t eat because it upsets Frane’s stomach, salads without garlic have no taste, I say. A bit of haggling over the price is a must, for the pure fun of it; cheese and single cream for breakfast, the peasant woman will take the cheese out of the cheesecloth and scoop the cream out of the tub with a ladle, it will all be delicious. We’ll buy the hard cheese at the shop, along with the cold cuts, some roast ham, some aromatic kulen sausage links, smoked in pork intestines, that come from Slavonia and which he loves. And for our first lunch we’ll have fish, say mackerel, which he will bake, because his father bakes them. At our house we only eat sardines, which my mother prepares and cooks. And in our shopping bag there’ll also be peaches for the wine, tradition is tradition, I think happily as we see Danica and Frane off. They’re taking two pre-war leather suitcases with them on the train. They’re calf leather, but you can see that they are old, they’re scuffed, especially along the edges, and grimy somehow, like their once-gilded clasps that are now dotted with light spots. The suitcases would join the junk up in the attic if they had the money to buy new ones.

The Esplanade’s guests were no longer kings, or dukes, or exotic maharajas – now they wore the officer uniforms of the Wehrmacht, the Gestapo, occupiers to some, allies to others, depending on how you looked at it.”

It’s the first time Danica and Frane are going anywhere – at least since I’ve known them – the first time they are visiting the town where his father grew up, as a gentleman, a gentleman, his son keeps repeating, never having forgiven him for being a gentleman, well-born, upper-crust, with an ancestry and money and a mansion and power, somebody who wasn’t a nameless face in the crowd, part of the amorphous mob, only to become a nobody in this town, and to pass that on to his son, as if to mock him.

Frane left Dubrovnik around the age of thirty, trained to work as a hotel manager in Zagreb, and for a few glorious years was the assistant director of the Hotel Esplanade, and he married a pretty woman ten years his junior who worked for a lawyer, the world was open to him even if there was a war on, because there are those, you know, who navigate their way through war as if it didn’t exist, they don’t take sides and they don’t get involved. The Esplanade’s guests were no longer kings, or princes, or dukes, or exotic maharajas, they were no longer famous actresses, dancers, singers, writers or shoe moguls – now they wore the officer uniforms of the Wehrmacht, the Gestapo, occupiers to some, allies to others, depending on how you looked at it; they took over the hotel, along with the personnel. The hotel offered its services to those who could pay for them, and that now meant these people in uniform: welcome to our hotel… And then the war was over, the uniforms discarded, those still in uniform were killed, imprisoned or banished, and those who had once welcomed them, received them, tended to them, cleaned for them, cooked for them and along the way chatted with them and even had a drink with them, would now pay the price for having provided their services to the occupiers – because they were no longer allies – even though that had been part of their job description and they described themselves as being neutral. But there is no being neutral in wartime, there is no doing things halfway… It didn’t help if you gave some money to support the partisans, like Frane, or felt compassion for the weak and persecuted, you should have picked up a weapon and not played the fool, kowtowing to criminals. Now, deputy director, you will see what it’s like to be out in the street, said the authorities, and be grateful that we didn’t hang, execute or banish you, be grateful that you can even stay here. True, he was left with nothing, except his life, which was the greatest favour that those interesting times could render; as the Chinese famously said: God forbid you should live in interesting times.

The jealous neighbour could not forgive the executed man for being an upper-crust gentleman when he himself never would be, so it was onto the rubbish heap with the upper-crust gentleman, as prescribed by all wars.”

Meanwhile, in Dubrovnik, his younger brother was executed in the clamour to find people to blame for all that had happened, which some used to settle personal matters, like the jealous neighbour who could not forgive the executed man for being an upper-crust gentleman when he himself wasn’t and never would be, so it was onto the rubbish heap with the upper-crust gentleman, as prescribed by all wars.

Frane’s response to all this was bronchial asthma, because that’s the easiest, you languish, everybody runs around pampering and nursing you, feeling guilty about the good health they enjoy that you had been denied, so that in the end your illness is the only problem you have left, and it takes priority over everything else. I realised this last part watching my father die for over ten years, poor man, poor thing, such bad luck, such a pity, and still young, everybody felt sorry for him, although he slept as much as he wanted, got up when he wanted, did what he wanted, read detective stories and westerns while my mother was killing herself with work, the entire burden of life on her shoulders, but she wasn’t a poor thing, a poor woman, they weren’t sorry for her – because she was healthy.

This is what I am thinking as I see Danica and Frane off on their trip to Dubrovnik, with their battered suitcases and hand-made tote bag, made of bast fibre, bought from the blind, packed with breaded chicken, tomatoes and layer cake, which they’re taking with them on the train because it’s a long trip. Their last words of warning before they leave is, the gas, don’t forget to turn off the gas, and of course the light, don’t leave the light on all night, and also be careful not to burn anything, set fire to anything, or leave the door open when you go out, or forget the keys and have to force open the lock. As if we are children or feeble-minded; we roll our eyes but we nod yes to everything they say. After we kiss them goodbye and wave at them from the balcony until the taxi arrives, and then, laughing like crazy, return to the kitchen where breaded chicken, tomatoes and layer cake are waiting for us and I start talking about all the things we’re going to do over the next five days and what fun we’re going to have now that we’re finally alone, from cooking at home to going out, and we’ll go to the zoo and look at the animals, because I’ve wanted to do that for a long time, and the zoo is not far from the flat – I learn that actually we’re not going to be on our own because that same evening the daughter of his mother’s cousin is coming from the provinces to stay with us, somebody named Rafka, short for Rafaela I suppose, twenty-three years old, she’s coming for some medical check-ups and will be staying for three days… Almost until they come back!

The days, OK, she’ll be a pain, but the nights, now that’s a betrayal, I think to myself, in defiance of all logic – why would it bother me for his relative to sleep here? – but it isn’t just bothering me, it’s killing me, I literally go icy cold.”

If he’d punched me in the face it wouldn’t have hurt as much as the news about the relative coming to stay, disturbing our five days, which I’d already planned in my mind, like an annoying fly trapped in a room with you, and there wasn’t an inch of room for her, let alone for her stay overlapping with our five days, and nights, when I won’t be here. The days, OK, she’ll be a pain, but the nights, now that’s a betrayal, I think to myself, in defiance of all logic – why would it bother me for his relative to sleep here? – but it isn’t just bothering me, it’s killing me, I literally go icy cold, as if it’s minus a hundred degrees both outside and in, I gasp like a fish tossed onto the quayside where it’s destined to die. I don’t even touch the drumstick he left, because he likes only white meat, or the tomatoes or the layer cake, which I love. I just drink my red wine, which I still drink even today, and smoke and run my fingers through my hair and sulk so that I stop laughing, and wonder why his parents hadn’t mentioned this relative before they left, not a word, I note, despite all the instructions they had for us. And you knew, too, but you kept quiet about it, I say. Then I’m told that his parents didn’t know about it, the cousin announced her daughter’s arrival out of the blue, when they were packing, and they couldn’t say no, and he was caught off guard, he forgot to tell me, and they probably guessed that having the girl stay would be a bother so they avoided saying anything. Blah, blah, blah… But as far as I’m concerned, all my plans have gone down the drain.

The day that started like a joyous song has turned into the hush of a funeral and just before its end the girl appears, tubby, the white flesh quivering under her chin and forearms, with stocky legs but in a mini, she’s got no shame, I say to myself, and a biggish hawk nose, eyes close together, a bird woman, especially with her hair pulled tightly back into a ponytail, leaving her face completely exposed. She’s wearing gold earrings with red glass chips in the shape of a flower, they’re not rubies, they’re ordinary paste, I notice, I don’t wear earrings at all. I haven’t even had my ears pierced. Strangely enough, she hasn’t dyed her hair though it’s a forgettable brown, her almond-shaped eyes shoot all over the place, but sneakily somehow, as if she’s looking for things to steal from the flat, and she’s constantly grinning, but she’s not relaxed, she’s on guard. I don’t understand a thing. She’s got a great appetite, even though she’s supposed to be unwell, it’s her thyroid, she says, polishing off the layer cake, I’m surprised she even knows what a thyroid is because she looks uneducated somehow, actually she looks awkward, that’s the word that best describes her, awkward in her body, in her thoughts and in her speech, and this awkwardness somehow fills the flat, rising and expanding like baker’s yeast, pushing me out of the room. I can hardly wait to leave.

The next day they’re having coffee in the kitchen, I can hear the laughter even before I ring the doorbell, it’s convulsive, too loud, mocking, the kind in which every mouth opens wide, and I don’t like walking into a house where there’s that kind of laughter, as if it’s directed at me. She’s all ready to go out in her denim mini and green top with blue polka dots to match the denim, the top so tight that it reveals rolls of fat, topped off by black platform sandals. He’s in his pyjamas.

He’s already shaved, has patted on some 4711 cologne, which his parents adore, and can’t stop yawning. I tell him he looks as if he’s had a sleepless night, I’ve got my suspicions, but the kind that you don’t want to believe.”

Nevit Dilmen/Wikimedia Commons” width=”234″ height=”234″>She says she was waiting to say hello to me before leaving, no need for that, I think, but I’m polite and it’s not her fault that she showed up at the wrong moment, and sick to boot.

Nevit Dilmen/Wikimedia Commons” width=”234″ height=”234″>She says she was waiting to say hello to me before leaving, no need for that, I think, but I’m polite and it’s not her fault that she showed up at the wrong moment, and sick to boot.

After she leaves I say it’s strange that she came just when his parents went on a trip, that she didn’t know they were going when she announced her arrival, just where did she think she would sleep if they were still in the house, with them in their room? Yes, on the ottoman, my one and only says from his bed, in a fit of coughing, and I think to myself, this is all so pathetic. She returns in the afternoon, he fries some mackerel and we lunch together, talking about nothing in particular, and then she goes to lie down. I notice that she has a strange way of eating, leaning into her plate as if about to fall into it, and then putting her arms around it as if afraid somebody would snatch it from her. In the evening, we take her to the cinema and then for a drink and I’m so angry I could kill him.

She leaves in the morning, just before his parents are due back, unobtrusively, like a serpent, like the daughter-in-law who turns into a snake in the fairy tale ‘Stribor’s Forest’, she simply vanishes. We didn’t even say goodbye to each other. When I arrive at the flat he tells me he took her to the train station early that morning, that her medical results were not good so she was in a hurry to go home. He’s already shaved, has patted on some 4711 cologne, which his parents adore, and can’t stop yawning. I tell him he looks as if he’s had a sleepless night, I’ve got my suspicions, but the kind that you don’t want to believe, so you’re happy when they persuade you otherwise.

But I keep thinking about the other day, when I saw him lean down to her yellowish-white, bullish neck, as if wanting to inhale her scent, and she giggled, threw back her head, making the gold earrings with their red glass chips in the shape of a flower swing, and opened out her arms as if to stretch, which lifted her breasts, they were quite literally bursting, probably full of milk because she had just had a baby, and the expression on his face was the same as when he was telling me about his mistress’s tail, satanic, as if they half disgusted and half excited him.

From Wild Woman (Istros Books, £10.99)

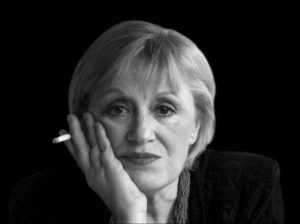

Marina Šur Puhlovski was born in Zagreb where she attended high school and graduated with a degree in comparative literature and philosophy from the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. She has worked a journalist and a literary critic, written stories, novels, travelogues, essays and literary diaries, and been the recipient of several national awards for literature. Wild Woman, her first work to be published in English, is out now from Istros Books, translated by Christina Pribichevic-Zorić.

Marina Šur Puhlovski was born in Zagreb where she attended high school and graduated with a degree in comparative literature and philosophy from the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. She has worked a journalist and a literary critic, written stories, novels, travelogues, essays and literary diaries, and been the recipient of several national awards for literature. Wild Woman, her first work to be published in English, is out now from Istros Books, translated by Christina Pribichevic-Zorić.

Read more

@Istros_books

Christina Pribichevic-Zorić has translated over 35 translated works of fiction and non-fiction from Serbian/Croatian and French into English, and is a recipient of the Serbian PEN Award for Translation, the Djuro Daničić Award for Translation and Radio Yugoslavia’s Award for Outstanding Achievement. She is a member of the Board of Trustees at the Media Diversity Institute, London, English PEN and the Advisory Board of the Central & East European Book Project, Amsterdam. She is the translator of Filip David’s The House of Remembering and Forgetting for Istros Books.