Outsiders within

by Sharon Bala

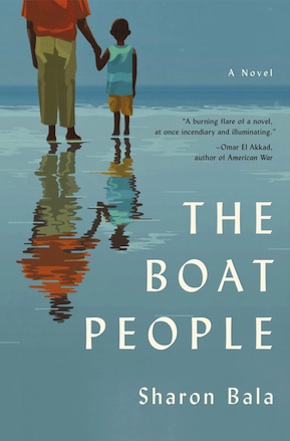

“A burning flare of a novel, at once incendiary and illuminating.” Omar El Akkad (American War)

Somewhere in the world, there is always a refugee crisis, people on the run from famine or conflict or natural disaster. I began writing my novel The Boat People in 2013 when the Syrian War was in its second year, just as the life rafts started to appear on the Mediterranean. As I wrote and revised, this story about people fleeing civil war, taking their chances on a dubious vessel that might just get them drowned, the calendar rolled on. 2013 turned into 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, and media coverage about refugees hit fever pitch. The situation in Syria was worsening then there were North Africans and Ukrainians, people fleeing the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Every day there was a new heartbreaking image – lifeless bodies washed up on beaches and people trapped behind fences, their fingers curled in the chain links. In Europe, in North America, debate raged: open the door or bolt the lock? The news reported all the usual stories, but there were stranger accounts too. For the first time, I heard about the Pacific islands of Nauru and Manus where Australia outsources its refugee problem by funding immigration detention centres. Out of sight, out of mind, asylum seekers languish indefinitely on these remote islands, their hope trickling away with each passing day. Listening to a podcast, I learned about Eritrean refugees who were captured and held for ransom in the Sinai dessert. There were winners and losers, it seemed, in the global refugee crisis. New industries springing up to capitalise on the disaster.

In another radio story, a reporter interviewed people in a German refugee camp who were convinced Chancellor Angela Merkel was en route to end their purgatory, to close the place down and send them to more permanent homes. “Mrs Merkel is coming,” they insisted and I found that statement, its certainty and optimism, so poignant that I replicated a version of it in my novel.

After the British ceded control of Sri Lanka, the majority Sinhalese looked around and decided the minority Tamils possessed too much wealth and privilege, too many of the best jobs. The majority felt disenfranchised.”

The asylum seekers in my book hail from Sri Lanka, a small island nation in the Indian Ocean. For nearly thirty years, the country was mired in a bloody civil war fought between the majority Sinhalese and the minority Tamils. To outsiders they look the same. But any Sri Lankan can distinguish at a glance who is Sinhalese and who is Tamil. There are subtle cues that differentiate, like skin tone and nose shape, the sharp angle of a chin. There are other differences, too. Tamils are Hindu. Sinhalese are Buddhist. Their languages are as different as English and Russian.

After the British ceded control of Sri Lanka back to its own people, the majority Sinhalese looked around and decided the minority Tamils possessed too much wealth and privilege, too many of the best jobs. The majority felt disenfranchised, hard done by. Who did these upstart Tamils think they were? They should go back to where they came from. Never mind that the two groups have lived together on the island for several millennia, to many Sinhalese, India, that giant Hindu nation, is where all Tamils rightly belong. And so war was raised with battle cries of “Sinhala first” and “Sri Lanka for the Sinhalese.”

In 2016, as I was deep into revisions at home in Canada, I tilted an ear across the pond and heard a similar sentiment as the referendum on Brexit neared. People who felt disenfranchised by job loss and poor financial prospects blamed their troubles on open borders, union with Europe that had enabled the influx of different accents and nationalities. What are all these foreigners doing here? some voters wondered. They’re taking away jobs from ‘native-born’ workers.

Over in the United States the same story was playing out. “America First” the new president declared. Who do these “bad hombres”, these brown-skinned people, who do these minorities think they are? They should go back to where they came from.

Britain First. America First. Strident right-wing movements in France, Hungary, and elsewhere. These are stories that have played and replayed, all over the world, throughout all periods of history. You need not look overseas or even far back in time to see them. One minor storyline in my book is a reckoning with the Japanese-Canadian internment during World War II. Under the guise of national security, Canadian citizens of Japanese heritage were rounded up. Overnight, people were stripped of human rights, lost their homes and livelihoods.

In my research I came across some rather colourful wartime propaganda and one image in particular that I recreated in my book. In a cartoon drawing, a caricature labelled ‘Jap’ leers menacingly with a knife while standing over a prone feminine figure dubbed Canada. Today we have slick memes, fake videos of men – purported to be Muslims, immigrants – destroying statues of the Virgin Mary, beating a child on crutches, and politicians who gleefully retweet propaganda as if it were fact.

I set out to write a story about the past. But time marched on as I drafted and revised. History began to repeat itself.”

My novel is set in 2009. It deals with atrocities that began in Sri Lanka in the 1950s, that took place in Canada in the 1940s. I set out to write a story about the past. But time marched on as I drafted and revised. History began to repeat itself and I suddenly realised this book about the past had more and more to say about the questions we grapple with in the present. Will we ever learn from our mistakes? The rallying cry of Sinhala First, Germany First, Britain First. The ‘outsiders’ we decide can’t be trusted – Japanese, Tamils, Muslims.

If the news shocks and awes, then it is the job of fiction to win hearts and minds. We are so insulated, surrounding ourselves with people who look and think and act just like us. We can barely understand neighbours who vote differently in a referendum or for the other party, so how can we possibly comprehend, let alone sympathise with a person from the other side of the world? Imagine, the writer urges. Just imagine you were born into a life very different from your own. For many, a book is the only introduction they will ever have to a border crosser, a boat person, an ‘outsider’. By reading about real and compelling characters who we care about and root for, we open the door to empathy, and the possibility of a future that looks nothing like the past.

Sharon Bala was born in Dubai, raised in Ontario, and now lives in in St. John’s, Newfoundland. The Boat People, published by Doubleday, is shortlisted for the 2018 Amazon Canada First Novel Award.

Sharon Bala was born in Dubai, raised in Ontario, and now lives in in St. John’s, Newfoundland. The Boat People, published by Doubleday, is shortlisted for the 2018 Amazon Canada First Novel Award.

Read more

sharonbala.com

instagram.com/sharon.bala

Author portrait © Nadra Ginting