Homing in on Hopper

by Christine Dwyer Hickey

“A profound understanding of human weakness and longing and regret.” The Irish Times

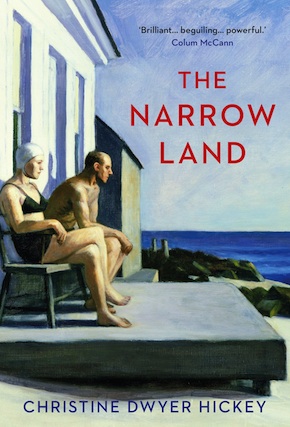

I have always been a bit sniffy about biographical fiction, the mining of a personal life for the sake of a story, particularly when that person is no longer around to defend him or herself. So how come I ended up writing a novel about one of the greatest artists of the 20th century – a man who was so private he would take the long way home rather than risk running into a friendly neighbour? To explain and perhaps excuse myself, I will have to take you back to the beginning.

President Truman’s Directive on Displaced Persons, 1945

In 2012 in Leipzig a man told me a story about malnourished children in post-war Germany who were sent off to farms to recuperate. I dug a little deeper and came across President Truman’s Directive on Displaced Persons published a few months after the war. Truman wanted to take orphaned children, regardless of their origin, from European holding camps and bring them to America to be adopted. An image began to form in my mind of a group of boys on a train dressed in patched-up clothes made out of dead soldiers’ uniforms. Like little piggies getting fattened up for the American market, I had thought, and this phrase, along with the image of the boys, stayed in my mind.

Berlin: The Downfall, 1945 by Antony Beevor

I simply couldn’t get this book out of my head – the suffering experienced by Berliners in general and women in particular at the end of the war. I could see the devastated city: the walls made out of sandbags, the hills of rubble. I could see the Trummerfrauen – the women of the ruins, crawling all over this rubble in organised teams, scavenging for anything of value while, in true Hausfrau fashion, setting about cleaning up the mess that was now Berlin. And I could see my little boy at three years of age, wandering lost and alone through the ruins.

This tour consisted of one lady driving us around the more remote areas of the outer Cape. We were shown locations painted by Hopper, and fed a few gossipy snippets which may or may not have been true. I was very much taken by the scenery anyhow, the purity of the light, the sense of being on the edge of the world. I knew then that my next novel would be set in Truro on Cape Cod, and that somehow my little German boy would feature in it. At this point it occurred to me that Hopper might make a cameo appearance. A silhouette in the distance perhaps, standing at the easel, while the boy played below on the beach.

Pamphlets: Remember When, 1947–1950 (KardLet)

Pamphlets: Remember When, 1947–1950 (KardLet)

I set my novel in 1950 because it was a pivotal time in American society. These pamphlets were packed with incidental gems such as the cost of living, the food people ate, wages, etc. There were plenty of ads too, most of which were aimed at the American housewife – a concept that had been heavily marketed since the end of the war perhaps by way of compensation to those women who gave up their wartime jobs to the returning heroes. In return there was the promise of a station wagon in the driveway, appliances in the kitchen, a frilly apron to tie around your waist, and a husband who called you ‘Honey’ (what more could a girl want?) The age of consumerism was in full swing, people had grown used to peacetime and then, out of the blue, war broke out in Korea.

Documentary: Edward Hopper and The Blank Canvas

With work on the novel barely started, it was discovered that I had cancer in one of my kidneys and would have to have it removed. The recovery was long, exacerbated by bouts of insomnia. I lost all interest in my work. Then one afternoon while flicking through the TV channels I came across a documentary on Edward Hopper. It showed his summer house in Truro, the acres of beach below it, the sea spiked with blinding light. The accompanying music was soft and soothing; within moments I was asleep. It became a thing, watching this documentary, sometimes falling asleep, but gradually staying awake for longer. I began to study Hopper’s face; his large, still hands; his slow, cautious voice. I studied Jo too, his wife and fellow artist, her petite frame and birdlike movements. Her fast, effusive speech. I heard an underlying tone of disappointment in her voice. I began to enter the Hoppers’ marriage.

Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography by Gail Levin

This biography doesn’t always paint Hopper in the best light, in fact there are some rather disturbing revelations: that he was violent towards his wife and blocked her career as an artist, for example. I had difficulty equating the man in the biography with the gentle chap I had seen in the documentary. Nor could I quite see Jo as victim to his villain. I reread the biography, and I began to notice the negative comments about Hopper came from one source: his wife. Through abstracts taken from her journal as well as letters to friends, these accounts varied – one day he was a prince among men, the next she was calling him out as a monster. The biography made it clear that she was a volatile woman and yet it seemed to accept all of her negative claims against her husband. At the same time, their mutual friends had nothing bad to say about Edward but plenty of criticism to throw Jo’s way. The desire to give Edward Hopper a voice was the final push towards bringing the Hoppers into the heart of the novel. I wanted to hear both sides of the story, as is the instinct of the novelist.

I was in Montreal at a writers’ festival when I heard Gustav Holst’s The Planets at Maison Symphonique. Each of the seven movements in this extraordinary suite seemed to be relevant to my characters, and the map of the novel was laid out before me like a gift from the heavens. The first movement, The Bringer of War, was the impetus. This was Jo Hopper, a woman who would fight for her beliefs come what may. But my refugee boy was also the Bringer of War, a child who would carry the memory of war deep within his psyche for the rest of his days.

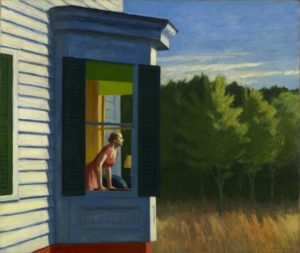

Cape Cod Morning (1950) by Edward Hopper. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington

Photograph: Edward Hopper and his sister Marion aged 8 and 10

This photograph and other family pictures inspired me to visit his boyhood home in Nyack outside New York City. The house, which is open to the public, is very much as it would have been in Hopper’s youth. I was able to stand at the window of his bedroom and look out at the bouncing mosaic of light on the Hudson River that was his boyhood view. Light was everywhere in that house, cast in geometric shapes across the floorboards and walls.

Cape Cod Morning (1950) Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington

I first saw this painting in Washington about ten years ago and it had an unsettling effect that never really left me. Completed at the end of the summer of 1950, the plot of my novel tapers towards it. I imagined the circumstances around the painting – what brought the woman to the window, what she was looking for, what happened the evening before and in the hours that followed.

Fisher Beach, Truro, Cape Cod

For all the research carried out, there is nothing to beat going to the location in question and planting your feet on its ground. And so I returned to Cape Cod, found a house to rent along Fisher Beach and for a few weeks became a neighbour of the ghosts of Mr and Mrs Hopper. I walked along the same shore, breathed the same air, wandered up to the vacant house, sat myself down on the slated porch chairs and it often felt as if I was sitting beside them as they looked down from their bluff on the sea.

Christine Dwyer Hickey is a novelist and short-story writer. Her novel The Cold Eye of Heaven won The Irish Novel of the Year 2012 and was nominated for the International IMPAC award. Tatty was shortlisted for Irish Novel of The Year 2005, nominated for The Orange Prize and listed as one of the 50 Irish Novels of the Decade. Last Train from Liguria (2009) was nominated for the Prix L’Européen de Littérature. Her short stories have been published in anthologies and magazines worldwide and have won several awards including twice winner of The Listowel Writers’ Week short story competition and winner of the Observer/Penguin short story award. She was longlisted for The Sunday Times EFG Short Story Award 2017 and her story ‘Back to Bones’ was the winner of the Short Story of the Year Award at the Irish Book Awards 2017. An elected member of Aosdana, the Irish academy of arts, her work has been widely translated into European and Arabic languages. Her play Snow Angels premiered at the Project Arts Theatre in 2014. Her eighth novel The Narrow Land is out now in hardback and eBook from Atlantic Books.

Christine Dwyer Hickey is a novelist and short-story writer. Her novel The Cold Eye of Heaven won The Irish Novel of the Year 2012 and was nominated for the International IMPAC award. Tatty was shortlisted for Irish Novel of The Year 2005, nominated for The Orange Prize and listed as one of the 50 Irish Novels of the Decade. Last Train from Liguria (2009) was nominated for the Prix L’Européen de Littérature. Her short stories have been published in anthologies and magazines worldwide and have won several awards including twice winner of The Listowel Writers’ Week short story competition and winner of the Observer/Penguin short story award. She was longlisted for The Sunday Times EFG Short Story Award 2017 and her story ‘Back to Bones’ was the winner of the Short Story of the Year Award at the Irish Book Awards 2017. An elected member of Aosdana, the Irish academy of arts, her work has been widely translated into European and Arabic languages. Her play Snow Angels premiered at the Project Arts Theatre in 2014. Her eighth novel The Narrow Land is out now in hardback and eBook from Atlantic Books.

Read more

christinedwyerhickey.com

@AtlanticBooks

Author portrait © Dierdre Power