A red sun setting over ruins

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“Sotiropoulos notices every encounter and records every intuition with a lyrical, impressionistic style of her own. A perfect book.” Edmund White

Modern Greek literature is often viewed with relative suspicion when translated or transposed for the foreign reader beyond its borders; it is deemed perhaps too local and of limited or specialist interest, too parochial and unmodern, or as a weak, nerveless attempt at emulating Western fads and already expired fashions. Greekness is inevitably dominated by ancientness, as though the sluices of the country’s history and humanity had been hermetically shut sometime in a distant past; ever since then, it can only lay claim to an eternal silence, like the that of the spring of Apollo and the inspired mouths of his Pythias.

And yet the country’s writers with the greatest resonance abroad are the ones who have been insatiably and uncompromisingly ‘Greek’ – Sikelianos, Seferis, Ritsos, Kazantzakis, Elytis, Papadiamantis, Cavafy, Valtinos, are perhaps the names that might stir most successfully a memory, or spark some faint sense of recognition. Among them, Constantine Cavafy was the one most spectacularly, emblematically and indomitably Greek, an idiosyncratic Hellene to the bone, and he is the one who received the greatest renown, and even dubious celebrity. He was (inadvertently, surely) included in the funeral of Jackie Kennedy-Onassis, and enjoyed the more substantial admiration of such men of his generation as E.M. Forster, T.S. Eliot, Arnold Toynbee and T.E. Lawrence, but also of women, such as Marguerite Yourcenar. Even more impressively, he has inspired a more contemporary and very long cohort of translators, most of them poets themselves, who have sought to celebrate, decipher and relocate him.

Even in his own time, Cavafy was a distillation of the trauma and the thrilling burden of being Greek – of being ineluctably attached to a fabric of history that is both indestructible and constantly unravelling, of being a member of a community whose identity is a constant struggle between flux and fixation. A nouveau-pauvre, he was an aristocrat who had all but lost his membership card to an elite club audaciously striving to find its own place of modernity; an expat, he was a unique combination of the man of the world and the oblate; he was the son, brother, uncle who also had a seductive life as a poet, and a private life of passions that could only be mentioned (and perhaps lived) in deflected terms.

It may have been Cavafy’s relative exile or cultural isolation in Alexandria that provided him with the fertile vacuum he felt compelled to fill.”

Cavafy would come to live many lives, and his biography – even the scant scraps and faded traces that we still possess – reveals multiple layers of existence, both personal and more historical, that are redolent with the hues and echoes of many images and voices. Ottoman Constantinople (invariably described as belonging to Byzantium/Turkey in biographical notes of the time), Liverpool and London, and finally Alexandria, a city Cavafy’s niece would describe as “a cargo train carriage, full of Greeks, Israelites, English, French, Italians and Lebanese”, a melting pot of languages, races and cultures, a pressure cooker of tensions and contrasts, of social inequalities and rival perspectives. Cavafy can be said to have been a citizen of each and all, a flesh-and-blood realisation of the Hellenistic dream of a cosmopolitanism that reconciled but also nurtured diversity.

For many, Cavafy is a literary and historical outsider, an eccentric genius, as well as a congenial figure standing at “an angle to the universe” as Forster would aptly put it; offering a “unique perspective of the world” in Auden’s words. And yet Cavafy had known a life of opulence and social busybodiness, he had belonged to the circle of those who mattered, the game changers, movers and shakers of the time, before his family’s fortunes were ruined and he had to find a post as a clerk, and then director, in the Egyptian Public Service. Like Wallace Stevens, E.E. Cummings, T.S. Eliot and so many others, Cavafy had to have a day job, as well as a life of spiritual freedom and exaltation in poetry. This double identity adds another chiaroscuro layer to his poetry, just as it does to his life, endowing it with a particular sense of public interiority, a voice that, while private, has an exceptionally strong sense of an audience. One can in fact argue that it may have been Cavafy’s relative exile or cultural isolation in Alexandria that provided him with the fertile vacuum he felt compelled to fill, and also with the sharper critical distance from affectation and imitation, from almost all anxiety of influence.

Cavafy was certainly not a recluse. Nor was he a repressed Dorian Gray figure. He was an avid tennis player, a gambler and chain-smoker, a shrewd investor and broker (he was a member of the Egyptian Stock Exchange) and for a time a journalist; he loved his drink, and was by all accounts an experienced, charming host and a rather skilled dancer. He could be suave and cantankerous; embarrassingly generous and at least momentarily mercurial; an endearing uncle full of mesmeric secrets and knowledge emerging from his study of coveted and fiercely guarded books, and a distant artiste; a loyal friend and brother, and a staunchly confirmed egotist. He certainly struck a pose and relished the journey to his own Ithaca of understanding, discovery, revelation and indulgence, a journey that according to an apocryphal story would conclude on his deathbed with a final, grand artistic gesture: just before drawing his last breath, and after having received holy communion, Cavafy sketched a circle on a blank piece of paper, and marked its centre with a distinct dot. A trou dans l’eau? A bullseye? He remained an enigma to the end.

For many, there are two Cavafys. The Cavafy of the historical poems, who created a brand-new vernacular out of what was always already there; and the sensualist peregrinator and collector of scents.”

What was the genius of this enigma? It is a question that has divided readers and critics ever since his first poems began to be circulated in small pamphlets to those he personally chose as his intended public. For many, there are two Cavafys and the rivalry between them is often claimed to be irreconcilable. There is the Cavafy of the historical poems, who created a brand-new vernacular out of what was always already there, and especially out of what is most essentially both Greek and Hellenic, but also ecumenical, atemporal, a new language for historical and human experience. Through the microcosm of the chosen ancient Greek, Roman, Hellenistic or Byzantine paradigms, Cavafy distils in its most vital form and poignancy the tragic sense of life, the desperate yet noble art of perseverance that derives from an exhausted, yet not extinguished hope. He also insisted on a sense of answerability, of a personal exposure to history, both Great History and the lesser narrative of impassive oblivion, failure, ineluctable fate – a now singular Greek Moira, invincible and omnipotent over both nations and individual lives, unless one can read and decipher the text of history, release the individual nous from the web of its narrative.

The other Cavafy is the sensualist peregrinator and collector of scents, the modern Odysseus whose Ithaca is the journey itself. This Cavafy was designated as the ‘forbidden’ one, and was the one beloved by Yiannis Tsarouchis, whose paintings capture that same sense of Sehnsucht, of a longing that both defies and venerates an impossible abandonment and nostalgia. It would be the one David Hockney would see almost exclusively as the poet’s power to speak to us, to unsettle, and especially to move us.

Yet both these sides of Cavafy share a common strand of subversive brilliance: Cavafy’s poetry is an unbuilding of inherited structures, of the permeating atmosphere, of movements and isms. His art is a ruthless stripping down to pure essentials that retrieves, at the same time, and by this relentless process of ‘make it less’, the deepest, most immediate humanity. To the disillusionment of the Romantics, the effete aestheticism of the fin de siècle artists, to the manifestos of symbolism, modernism, impressionism, imagism, and the sterility, as he saw it, of a Western canon, Cavafy counterposes with unshakable certainty the principle of a transcendental endurance – through history, through the presence and agency of the human individual across its course and in its every moment.

Cavafy was a caustic political observer who abhorred rhetoric as much as he despised a facile, pejorative vernacular of themes or language. His most singular trait is that of surprise – he stuns us with his erudition, the depth instilled in the few compact, simple lines of his poems, the intensity of the emotions behind a deceptively fleeting, everyday scene. Το Rimbaud’s muscular, Doric friezes of symbols and subliminal meanings, Cavafy offers Attic simplicity – and ultimately grandeur. He tried to be Rimbaud, to be an aesthete, even an academician or a neo-classicist. He failed miserably. And he thus succeeded in being utterly unique, consistently inspiring, one might even say eternal.

Sotiropoulos’ Cavafy will arrest your gaze and make you look closer, seek the echoes and the traces of a life whose fullness and stark abstraction cannot fail to mesmerise you.”

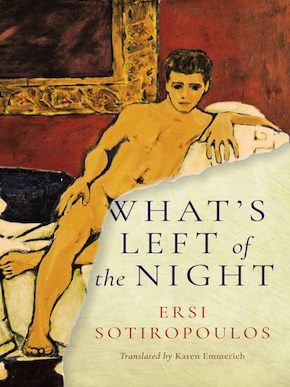

Ersi Sotiropoulos seeks to capture the very moment between failure and triumph; between mediocrity and true genius; her novel What’s Left of the Night is an audacious, decadent portrait of the well-to-do artistic scene in Paris, full of indulgently aesthete, untalented, naïve and conceited caricatures of men and women, the aura of an era. Her Paris is the Paris of Oscar Wilde, Proust and Huysmans, of occult, neogothic séances, decomposing tableaux, intricate reliefs of textures, smells, feelings, hidden meanings, dominated by the perfect polish of a life transmuted into art. Darkest decline meets the most brilliant triumph, or so the characters would like to believe. Dreyfus is in the background, as are the greatest artists and poets and the lowest vices, and Sotiropoulos is a fine storyteller with a taste for Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice and a particularly strong sense for scenography and drama. She gives us lavishly the thrill of the gutter (for those, at least, who can encounter its squalor and danger only as a form of sport) and the dazzle of luxury, conjuring up almost breathlessly tout Paris, the demi-monde and the beau-monde, especially the overpopulated hell of loneliness.

Hers is an unapologetic grand tableau of the sublime lure of decline and the beauty of a splendour long gone – the ghosts of her Paris are glorious, formidable, tragic, grotesque, inalienably the very soul of the city. She can offer riveting close readings and evoke the great discussions of the time – what is the value of art? Pleasure? To serve a purpose? Necessity? What is – can there be? – great art? Can everything and anything be beautiful? Who is the real artist? The quiet creator or the damned trail-blazer, l’artiste maudit? She is also a very keen observer of human nature, of the yearning for closeness and the horror of an overwhelming proximity. Her story has pulse, momentum, certainly a power one can call inspired.

Sotiropoulos’ Cavafy will not perhaps appeal to or convince every reader – of What’s Left of the Night or of Cavafy’s poems. Yet he will certainly arrest your gaze and make you look closer, seek the echoes and the traces of a life whose fullness and stark abstraction cannot fail to mesmerise you. Her prose has a distinct skill for suspense and tension, for a masterly reimagining of another life with daringly wielded poetic licence. She has a loyal second to her task in Karen Emmerich, who infuses the English text with the right musicality, pathos and relentless flow.

Ersi Sotiropoulos has written fifteen books of fiction and poetry. Her work has been translated into many languages, and twice awarded Greece’s National Book Prize, Book Critics’ Award and the Athens Academy Prize. The French edition of What’s Left of the Night won the 2017 Prix Méditerranée Étranger. The English edition, translated by Karen Emmerich, is published in paperback and eBook by New Vessel Press.

Ersi Sotiropoulos has written fifteen books of fiction and poetry. Her work has been translated into many languages, and twice awarded Greece’s National Book Prize, Book Critics’ Award and the Athens Academy Prize. The French edition of What’s Left of the Night won the 2017 Prix Méditerranée Étranger. The English edition, translated by Karen Emmerich, is published in paperback and eBook by New Vessel Press.

Read more

Buy at amazon.co.uk

@NewVesselPress

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.