The book of Sarah

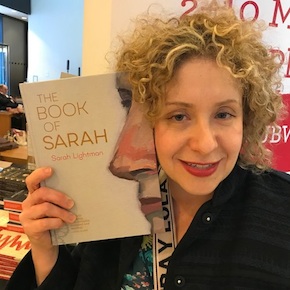

by Sarah LightmanThe Book of Sarah is a project that has covered thousands of pages of diary drawings, from hundreds of sketchbooks, beginning in 1998. These drawings chart my childhood and sibling rivalries, schooldays and intense religious orthodoxy when I studied in Jerusalem, my years at art school, a failed relationship in New York, my marriage and most recently the birth of my son. The Book of Sarah is also a feminist reparative act. My namesake, The Matriarch Sarah in Genesis, is frequently portrayed as lacking her own agency, and slips in and out of her husband Abraham’s story. I, however, am the heroine of this Book of Sarah. Furthermore, as I am commentating on my own narrative, my own book of the bible, I am in sharp opposition to Jewish traditional texts that propose an almost exclusively male intellectual heritage.

Much of my work was made during the times I was living the experiences I recorded. There are exceptions, however, and these include pages 33–37 (above), that were based on careful visual analysis of just one photo of me and my siblings as we loitered by a petrol station in Golders Green on the way to buy my brother his Bar Mitzvah suit. These drawings show my siblings and myself as we pose, push and squabble in this photograph. I lean on my sister, and also stand on her toe, whilst I consider how my brother is in denial about my own intellectual development: “I don’t think Daniel ever got over the shock of me learning Latin.” The struggle to find my own identity is reflected in the difficulty in initially identifying each of us in the opening image. I was born last, an interloper into the pre-existing structure of a family of four. In these drawings I describe it as “constructing yourself… in an already established community.” This struggle to find a foothold in the family unit is reflected in how I am standing on my sister’s foot, an image repeated three times in three pages.

An astounding work of insight and clarity… so eloquently expressed.” Stephen Holland, Page 45

My attempted effacement of my sister and my brother’s intellectual underestimation of me are more than symptoms of sibling rivalry; they are learned behaviour, which even at eight years old I was party to, and related to the effacement of women in Jewish traditional culture. It is significant that this struggle for identity occurs during this photograph, when my brother is being celebrated in Jewish ritual for embarking on his journey to becoming a man, because after his Bar Mitzvah he would be counted as contributing to a quorum of men in prayer. There was to be no equivalent event or family outing for myself, no big event surrounding the purchase of my Bat Mitzvah dress, nor was there one for my sister. It was my brother’s journey, as the firstborn son, and I and my elder sister were meant to play our parts as we accompanied him, whilst being aware that we were both excluded from any equivalent experience or honour and would never be recognised or counted in a quorum in the Orthodox Jewish community, or be recognised as intellectual equals within Jewish tradition.

Looking back on this photograph, I see I was fighting the structure around me. Though I was wearing the clothes I inherited, I still minutely rebelled, as I closed my eyes in the original photo, and on page 33. It was not from the sun in my face, but a very small act of subversion – I am present, but also elsewhere, inside my own space. I am here, but also I negate myself within this construct, a photographic equivalent to Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar’s discussion of literature: “Just as stories notoriously have a habit of ‘getting away’ from their authors, human beings since Eden have had a habit of defying authority, both divine and literary.” I escaped the tyranny of the family photograph by closing my eyes – I was looking into a future where I would live beyond the frames, looking beyond where I was placed, to a space I could make my own, escaping photographic boundaries. Did I ruin the photo at that moment by this act? No, as it remained displayed for years, my mother’s favourite of us. It was only much later that I ‘mutilated’ it for her with this series of drawings. My mother told me after that she could no longer gaze at the photo without being aware of all that my drawings say about the scene. Now you no longer find this photo on the shelf with her other silver-framed frozen memories. But notwithstanding that space on the shelf, years later I have made this moment my own, in a book of my own, a bible of my own, where I celebrate my thoughts, my religious commentaries and critiques.

Sarah Lightman is a London-based artist, curator and writer whose artwork has been exhibited in museums and galleries internationally. She co-curated the critically acclaimed touring exhibition Graphic Details: Confessional Comics by Jewish Women and edited the accompanying volume, Graphic Details: Jewish Women’s Confessional Comics in Essays and Interviews, which was awarded the Eisner Award for Best Scholarly/Academic Work, The Susan Koppelman Prize for Best Feminist Anthology, and an Association of Jewish Studies/Jordan Schnitzer Book Award for Jews and The Arts. Sarah has taught and lectured extensively, and is an Honorary Research Fellow at Birkbeck, University of London. She has led comics workshops at the Jewish Museum, London, Glasgow Jewish Book Week, JW3, London and Koffler Centre for the Arts, Toronto. She is co-founder with Nicola Streeten of the influential forum Laydeez do Comics, which meets regularly in London, Leeds, Bristol, Birmingham, Glasgow, Dublin, Chicago, San Francisco and Haifa. The Book of Sarah is published by Myriad Editions.

Sarah Lightman is a London-based artist, curator and writer whose artwork has been exhibited in museums and galleries internationally. She co-curated the critically acclaimed touring exhibition Graphic Details: Confessional Comics by Jewish Women and edited the accompanying volume, Graphic Details: Jewish Women’s Confessional Comics in Essays and Interviews, which was awarded the Eisner Award for Best Scholarly/Academic Work, The Susan Koppelman Prize for Best Feminist Anthology, and an Association of Jewish Studies/Jordan Schnitzer Book Award for Jews and The Arts. Sarah has taught and lectured extensively, and is an Honorary Research Fellow at Birkbeck, University of London. She has led comics workshops at the Jewish Museum, London, Glasgow Jewish Book Week, JW3, London and Koffler Centre for the Arts, Toronto. She is co-founder with Nicola Streeten of the influential forum Laydeez do Comics, which meets regularly in London, Leeds, Bristol, Birmingham, Glasgow, Dublin, Chicago, San Francisco and Haifa. The Book of Sarah is published by Myriad Editions.

Read more

sarahlightman.com

laydeezdocomics.com

@sarahlightman1