The secret mission

by Ludovic BrucksteinIn the few days that had elapsed since the ghetto was set up in the little Carpathian town of Ostrov, the Jewish Council, the so-called Judenrat, had succeeded in being neither good nor bad, but rather in being wholly naïve.

Appointed chairman of the council, Mr Faivel Fischknopf was an elderly Jew with a little pointed white beard. Just a few days previously, before being sent to the ghetto, he had been the owner of a haberdashery and dress shop, ‘Glove & Cane’, which had been taken over by a moustached man from across the Danube, after he had proven to the authorities, God alone knows how, that pure Aryan blood had flowed in his family’s veins since the time of his great-great-grandfathers, since the days of Attila, Tass and Töhötöm.

The chairman of the Jewish Council was therefore Mr Faivel Fischknopf, but from the very start its driving force was Moti Orentlicher, nicknamed Motke, a short, swarthy little man, with beady, badger’s eyes, a lively, enterprising travelling salesman, who had travelled all his life, selling all kinds of goods, so much so that you would have been hard put to list them all. In his time, he had sold every kind of paste, cream, powder: toothpaste, shoe polish, brass polish, washing powder. For a time, he sold various small textile products: handkerchiefs, shawls, washcloths, napkins, towels, headscarves. Another time, he had travelled with samples of alcoholic beverages: wines, liqueurs, slivovitz, this being perhaps his merriest period, since on his return he had used to taste the little sample bottles that remained in his valise, after which he would loudly tell jokes in his third-class compartment, and laugh and sing, thereby enlivening the whole of the crowded train carriage.

Well, on finding himself shut up inside the walls of the ghetto, this Motke Orentlicher had to find some way or another of releasing his pent-up energy. And he did so by tirelessly running back and forth all over the ghetto, dispensing advice left and right on how to keep the streets clean, on how to dispose of the waste, and more particularly, he would visit the Jewish Council three times a day, each time bringing a new idea.

Orentlicher came up with the idea of distributing a chocolate bar to each child in the ghetto every Friday. The idea was deemed excellent and unanimously passed, there were children aplenty, but where was the chocolate?”

His ideas were very good, there was no denying it, they were acceptable and even accepted, on the one side. On the Jewish side. For example, one day Orentlicher came up with the idea of distributing a chocolate bar to each child in the ghetto every Friday. The idea was deemed excellent and unanimously accepted by all the councillors of the Judenrat. So the idea was passed, there were children aplenty, but where was the chocolate?

Another time, Orentlicher proposed that a corridor for the Jews be made, like the one in Danzig, which is to say, that two side streets be authorised to allow the Jews to circulate freely as far as the Mental Hospital, where seventy-five Jews were interned, so that they could take them Jewish food, cholent and kugel, at least on the Sabbath. The proposal was enthusiastically accepted by the Judenrat, Mr Faivel Fischknopf, the chairman, even praised Motke Orentlicher for it, smoothing his pointed little white beard in satisfaction, the motion was passed, there were patients aplenty, but there was nobody to listen to the proposal: the town hall and the local police, which guarded the ghetto, gave orders, but they didn’t listen to even the most just and sensible Jewish proposals.

But you have to give Motke Orentlicher his due. Once, just once, one of his proposals was accepted, passed, and successfully put into everyday practice.

The ghetto’s Jewish Council received from the town hall lists of the Jews that had to be put to work, along with where they had to work. The ghetto therefore sent one hundred and fifty men to the railway depot to load coal into the locomotives’ tenders, three hundred and seventeen men were set to build dykes along the

River Inar, two hundred and thirty-four men were sent to break rocks to build the highway north of Ostrov, and so on. The list also demanded that two Jews daily present themselves at the Villa Rosa on Linden Street, No. 14, where a number of SS soldiers from the SD, i.e. the Sicherheitsdienst, or Reich Security Service, were quartered. The two had to be there at seven on the dot every morning to pump water to the villa’s kitchen and bath.

The Judenrat was about to send two stout fellows, butcher’s apprentices, but Motke Orentlicher jumped up as if scalded and loudly cried, ‘No! I object!’ Then, in a low, almost conspiratorial voice, he went on: ‘To do this job we need to send two intelligent men who speak fluent German. Understand? They need to have a fine nose… To sniff out what’s what there… To eavesdrop, maybe we’ll find out something in advance…’

And Motke meaningfully blinked his beady, badger’s eyes.

The motion was passed and at the same meeting, the two ‘pump men’ for the Villa Rosa were decided upon: Mr Mark Holoker and Lucian Bercu, a student. The two were like Laurel and Hardy, and then some. Holoker was very short and stocky, almost completely round, with a round head framed by a round ginger beard and a hat with a brim stitched à la Eden: he was a trader in horses’ oats, and had formerly done business in Germany. Bercu had blond hair, which he wore swept up, was as tall as a pike, and had a long throat, up and down which bobbed an Adam’s apple like a ping-pong ball. Lucian had been studying chemistry at university when he was sent to the ghetto.

At seven in the morning, on the dot, the two arrived at the Villa Rose, Linden Street, No. 14. A nondescript, expressionless SS soldier let them in. But how were they to smell anything? How were they to eavesdrop? They didn’t see a single SS man the whole day, let alone hear a single word of German. The pump was in the yard, a hand pump. The water was pumped up to a large cistern in the attic of the villa. When it was full, the water gushed down through a pipe under pressure.

Starvation had yet to strike the ghetto and when the two told of the slices of bread they had received, Orentlicher triumphally cried, ‘I told you! It’s a good sign. It means their intentions for us are not bad…’”

The pumping, which the two took in turns, was by no means an easy task. The two sturdy butcher’s apprentices would have been better suited. Mr Mark, with his à la Eden hat on his head and his patterned tie around his neck, sweated profusely and panted noisily, like a pair of bellows, and the young Lucian, thin and as long as a day of fasting, also breathed heavily. He had been twice given a postponement for national service due to anaemia and Basedow’s disease, or ‘incipient goitre’, as his medical report put it.

When the two returned to the ghetto after their first day’s work and told everybody that there was nothing to tell, that they had seen and heard nothing, the Council could not hide its disappointment and looked at Motke Orentlicher askance. But Motke was undeterred. ‘It’s only the beginning, let’s have a little patience, gentlemen, we’ll see later on,’ he said, blinking his little badger’s eyes meaningfully.

And he was right, that Motke. About two days later, as the two men were pumping and sweating away, an old soldier suddenly appeared from the kitchen, a one-eyed man with a bony face, who, without a word, gave each of them a very thin slice of bread and marmalade. Starvation had yet to strike the ghetto and when the two told of the slices of bread they had received, Orentlicher triumphally cried, ‘I told you! It’s a good sign. It means their intentions for us are not bad…’

And chairman Faivel Fischkopf smoothed his pointed little beard, and the other councils nodded their heads in satisfaction.

After another two days, they found out more. Leaving the gate of the villa, Lucian had almost collided chest to chest with a young SS officer. For a few moments they stood face to face, both of them lanky, both blond, thin, but one in shabby civilian clothes, which hung loosely from his body, the other in a crisp, carefully brushed green uniform, with a diagonal chest strap and service revolver, with highly polished boots.

‘Was?’ exclaimed the officer with a frown, looking at Lucian’s blond hair. ‘What? Haven’t they cut your hair? Hasn’t the order reached the ghetto yet?’

And without waiting for a reply, he quickly went inside the villa.

The two hastened to take that snippet of information to the ghetto. And it was true, that very afternoon, two policemen on motorcycles brought the order. Every man, woman and child in the ghetto had to shave their heads.

Motke Orentlicher rubbed his hands in satisfaction: ‘You see, we knew in advance…’

But half an hour later, the two policemen on motorcycles brought another order. Nobody in the ghetto was to be shorn.

Orentlicher was jubilant: ‘Didn’t I tell you? They don’t have any bad intentions for us, after all…’

About a week later, the head of every man, woman and child was shaved at Auschwitz.

All the Jews from the ghetto of Ostrov, the town in the Carpathians, were taken away in four transports of three thousand each, seventy people to a cattle truck.

In the final transport, in the lead cattle truck, chairman Faivel Fischknopf, Motke Orentlicher and the other members of the Jewish Council, the so-called

Judenrat, sat on the floor next to the pail of water and the toilet bucket. And transported in the rear cattle truck were the seventy-five patients from the mental hospital.

Three days later they arrived at Auschwitz.

None of them, neither the mental patients nor the mentally sound, not even Motke Orentlicher, had ever heard of Auschwitz before.

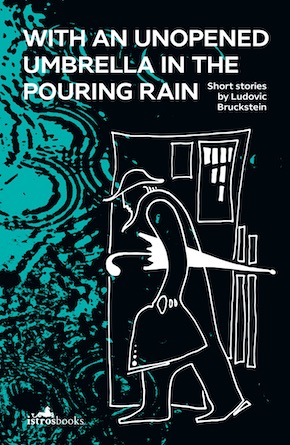

From the story collection With An Unopened Umbrella in the Pouring Rain, translated by Alistair Ian Blyth and illustrated by Alfred M. ‘Freddy’ Bruckstein (Istros Books, £9.99)

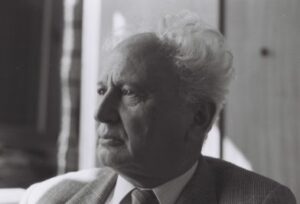

Ludovic Bruckstein in Israel, 1987 © Rita Bruckstein

Ludovic Bruckstein was born in 1920, in Munkacs, then in Czechoslovakia, now in Ukraine. He grew up in Sighet, a small town in the district of Maramureș, in the Northern region of Transylvania, a town well known for its flourishing pre-war Jewish community and Hassidic tradition. He wrote a number of successful plays including The Night Shift (Nacht-Shicht, 1947), based on the Sonder-kommando revolt in Auschwitz. His other works include the novel The Confession (1973), and the story collections The Destiny of Yaakov Maggid (1975), Three Histories (1977), The Tinfoil Halo (1979), As in Heaven, So on Earth (1981), Maybe Even Happiness (1985) and The Murmur of Water (1987). The Trap (two novellas) appeared posthumously in 1989, and in English translation by Alistair Ian Blyth (Istros Books, 2019). With an Unopened Umbrella in the Pouring Rain is published in paperback by Istros Books.

Read more

@Istros_books

Alistair Ian Blyth is one of the most active translators working from Romanian into English today. A native of Sunderland, he has lived for many years in Bucharest. His translations from Romanian include Little Fingers by Filip Florian, Our Circus Presents by Lucian Dan Teodorovici, Coming From an Off-Key Time by Bogdan Suceavă and Life Begins on Friday by Ioana Pârvulescu (Istros Books, 2020).

“My father understood the human soul.”

Read an interview with Freddy Bruckstein about his father’s work in The Calvert Journal