Seeds of change

by Helen PatuckWednesday 10 December 2014. Tonight is the night I leave Beirut with a suitcase full of my first children’s book, The Giant Watermelon, a bilingual Arabic-English story set in a refugee camp in Lebanon. It’s almost 4 am, I am sat at the airport and have just given a couple of copies to some curious Syrian children waiting to travel to America who have been watching me type this article. They have the biggest smiles on their faces as they ask why I wrote the book. I tell them it is a book for Syrian children who cannot travel like them, but who like the story as much as they do.

The Giant Watermelon is my first illustrated book in print: a tale about a magical watermelon, written for displaced Syrians and Palestinians who do not have access to formal education. I am bringing the book back to Europe to show family and friends over Christmas, who are probably wondering how I left Europe to learn Arabic in June and am returning to them with a dual-language literary project.

By trade I am a ghostwriter, but I left my office job in Geneva this summer to work freelance in Beirut and learn the Levantine dialect of Arabic. Six years ago I was in Syria and made friends there who suffered great losses during the civil conflict and later as refugees. A big part of my motivation to learn Arabic was to speak with my friends in their own language, though another part has been to live in Lebanon, a tiny, resilient country, bordered by decades of conflict.

The children in the camps we visited had little or no access to education. At one of the camps they took me to see their vegetable patch, where two watermelons were growing…”

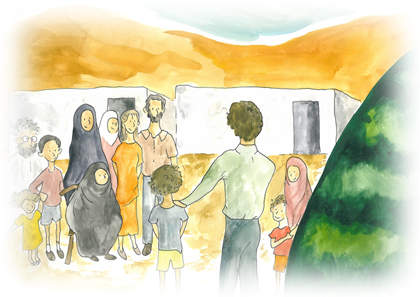

When I arrived in Beirut I made friends with Sarah Dusart, a Belgian social worker making a documentary about displaced Syrian children working in the city. Eventually we made our way to the refugee camps of the Beqaa Valley, bordering Syria, and it was there I discovered some of the hundreds of thousands of Syrian children living in camps known as Informal Tented Settlements. The children in the camps we visited had little or no access to education. At one of the camps they took me to see their vegetable patch, where two watermelons were growing, before asking me when their teacher Maya would come. Maya lived in Syria and they had not seen her for three years. With funding decreasing every year for educational organisations at work, and not enough room in Lebanese schools for the Syrians, I decided to write something the children could read at home. I wanted to make something to help them learn and enjoy reading at the same time. Inspired by their watermelons, I started writing a story.

Lebanese and Syrian friends helped me to translate The Giant Watermelon into fusha, the formal Arabic they would be learning in school. Friends in my Arabic class encouraged me to make the book into a project, and in September we came up with our name: Kitabna, which in Arabic, means ‘our book’. So now I write, illustrate, and distribute children’s books to displaced refugees, in the hope that they will find some joy in reading stories written for them, about them, with them. In November I picked an editing friend’s brain for copyright and ISBN advice, and sourced a printing press here in Beirut. We printed an initial 1,500 copies, and slowly but surely we are getting the books out into the camps.

Lebanese and Syrian friends helped me to translate The Giant Watermelon into fusha, the formal Arabic they would be learning in school. Friends in my Arabic class encouraged me to make the book into a project, and in September we came up with our name: Kitabna, which in Arabic, means ‘our book’. So now I write, illustrate, and distribute children’s books to displaced refugees, in the hope that they will find some joy in reading stories written for them, about them, with them. In November I picked an editing friend’s brain for copyright and ISBN advice, and sourced a printing press here in Beirut. We printed an initial 1,500 copies, and slowly but surely we are getting the books out into the camps.

It is hard to explain the daily movements of the project or to clearly envision how it will evolve. Next year I hope to take The Giant Watermelon to the wider Syrian diaspora in the Middle East, but I have a few more variables to consider than the average author, impending invasion from ISIS being the greatest. Closer to home, the increasing intolerance in Lebanon towards refugees has been hard to deal with. But when I look back at these first days of December, the next twelve months seem full of promise.

On the first day of December I headed to Dutch NGO War Child’s offices to receive a security briefing for our trip to the northern territories in Akkar region, just south of the Syrian border, to introduce The Giant Watermelon. We have been working more and more with NGOs who assist Syrian and Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. UNHCR and the International Rescue Committee are among the big organisations who have bought copies of the books for children they are working with. These sales subsidise our independent distribution in camps we have made contact with in the Beqaa Valley and suburban Beirut.

On the second of December I dropped off the artwork for a second book, Esraa’s Stories, at the printers. Esraa’s Stories is due to be printed in January, and tells the tale of a girl living in a refugee camp who loves to read and write stories. Her storytelling works in a way she had never imagined before. This book introduces the ways in which telling our stories can build catharsis and understanding of situations that are difficult to process.

On the third of December, I travelled to the northern border of Syria to War Child’s education centres. The sea was deceptively calm as it washed into a coastline that fringes a volatile area of border clashes and threats of massacre from ISIS. In a damp UNICEF tent I explained to nine teachers in Arabic why I had written The Giant Watermelon: to offer the children a book that both represents them, and can help them to read in formal Arabic and English. They loved the idea.

On the third of December, I travelled to the northern border of Syria to War Child’s education centres. The sea was deceptively calm as it washed into a coastline that fringes a volatile area of border clashes and threats of massacre from ISIS. In a damp UNICEF tent I explained to nine teachers in Arabic why I had written The Giant Watermelon: to offer the children a book that both represents them, and can help them to read in formal Arabic and English. They loved the idea.

On the fourth of December I sat with three wonderful women, Oula from Syria, Oana from Romania, and Sophie from Germany, in Beirut, to record the Arabic, French, and German translations of The Giant Watermelon for the e-Books we have created on our website. We were donated software by major online publication software developers 3D Issue to create e-Books to sell online as a way of making the project both financially sustainable and something the global community can get involved with. Since we have the software, and Beirut has such a strong and helpful international community, we thought we would create e-Books in the languages of all major resettlement countries in Europe.

On the fifth of December I travelled to the Beqaa Valley, as I always do on Fridays, to read with children in the camps. We read and distributed The Giant Watermelon in two camps, and enjoyed listening to answers to the question we always ask: what would you do if you had a giant watermelon? I invited an Argentinan friend visiting from London who works in the arts and migration field to come with me and see the book in action. During our visit she offered to translate the book into Italian and Spanish. For me this is the true magic of this story. Everything and everyone it touches inspires some kind of development or growth, which is exactly what I want the book to do in the minds and homes of the children we are reading with throughout Lebanon. I will never grow tired of seeing battered, dirty copies our book appear as I walk into a camp, or listening to the gradually improving recitation of the first line:

فِي الصَّيفِ الأَوَّلِ لَهُم فِي المُخَيَّمِ، فِي وَادِي البِقَاع، بنا طَارِقْ وأَبُوه حَدِيقَةَ خُضَارْ.

In their first summer at the camp in the Beqaa Valley, Tarik and his father built a vegetable patch.

Which is what I heard as I said goodbye and an early Happy New Year to the children in the camp we have been reading at in the Beqaa Valley for two months now.

On the sixth of December I got up early to read and distribute The Giant Watermelon with a group of Syrian children my Egyptian friends work with on a weekly basis in Hamra, Beirut. Later that day I formalised Kitabna’s partnership with a school in Mount Lebanon, Aley. From next January I will start an eight-week teaching programme around the book, teaching at the school every Monday. We have already decided to plant watermelons in the spring. Mohammed, the teaching director of the school, told me something that I will never forget: “The revolution in Syria was not beautiful, but what is happening here is. We have one hundred and seventeen children. This is our revolution.”

I am so proud to be part of Mohammed’s revolution, one that makes the education of Syria’s next generation a priority.

I am so proud to be part of Mohammed’s revolution, one that makes the education of Syria’s next generation a priority.

On the seventh of December I completed the German e-Book and delivered printed books to a friend to distribute to her office at UNHCR, where resettlement officers would like to place the book for their daily interviews with hundreds of displaced Syrians and Palestinians.

I saw the value of this the following day, when I waited for three hours at the General Security Office for my exit visa, allowing me to leave the country this morning. I chatted with and quietly admired the countless Syrians who sat and waited patiently for papers that would carry them away from their home and the civil conflict there. Later that day I was surprised to receive an email from a Lebanese illustrator, whose work is both beautiful and well-established in the Arab world, asking to collaborate. I was thrilled, not only because she loved the project, but because one of my main aims is to localise Kitabna to make it sustainable, something that can really grow organically here in Lebanon.

Yesterday I launched the German e-Book and packed my books to take with me to Europe, to my friends in Berlin, Geneva, and finally the UK. On the twelfth of December, I will be presenting the project and the German translation of the book, Die riesige Wassermelone in Berlin.

If this is what twelve days in the project look like, I can only begin to imagine what the next twelve months have in store. All I know for certain is that I have two more of my own books to go to print. Then perhaps we can begin our real work of asking the children to write their own stories, so we can produce Kitabna books written by the children themselves. At that point the project and the books will truly become kitabna, our book.

In Arabic there is a proverb that says: أول الشجرة بذرة , a tree starts with a seed. I hope we can make The Giant Watermelon into a giant reading initiative here in Lebanon; in refugee camps, in schools, and in all places where children want to read but do not have access to books.

Helen Patuck is a freelance writer, illustrator, photographer and literary consultant from the UK currently learning Arabic in Beirut. She ghostwrites novels and writes children’s books.

www.kitabna.org

Facebook: The Kitabna Project

Follow Helen on Twitter: @hvpatuck