The old she-wolf and the little girl

by Akiyuki NosakaIn Manchuria, now north-east China, a large she-wolf and a girl just four years old squatted in a sorghum field.

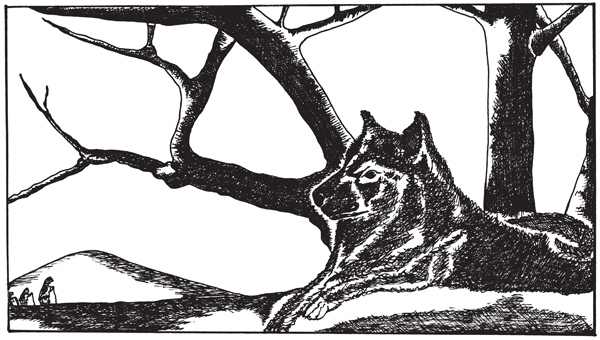

The wolf was sturdily built, but she was old and patches of her fur had fallen out and most of her teeth were missing. The little girl wore a white shirt with red baggy pantaloons, and was holding tightly onto a basket. They had been hiding here for two full days, as the earth rumbled from the countless large tanks heading south, and exchanges of gunfire sounded all around. Long ago, the old wolf had fled from humans with guns, and she had never forgotten the smell of gunpowder smoke.

The wolf was well aware that the time of her own death was approaching. Her eyes, which had once seen far into the distance even at night, were now blurred as if covered by a perpetual mist, and her ears, which had been able to distinguish between people’s voices in the village in the next valley, were now quite deaf, so all she had to rely on was her sense of smell.

Until two years earlier she had reigned as leader of the pack of fifty-two cubs that she herself had given birth to and raised, but as she began to feel her age she had ceded to a younger wolf, and once she knew the end was not far off she had quietly set out in search of a place to die.

When she had been with the pack, she hadn’t needed to hunt for food since the younger wolves would all offer her the choicest meat out of respect, and they had also taken turns to keep guard night and day, so there was no need for her to stay attuned to every noise.

Now she was on her own, however, she had to take care of everything herself. And with her nerves constantly on edge, her physical strength rapidly deteriorated. Although she was old, however, she did have her pride. It would be better to lie down on the railroad tracks that crossed the plain from north to south and be run over by a train than succumb to wild dogs or cats, she thought. And so she had once more drawn herself up and strained her useless eyes and ears to the utmost, hoping quickly to find a quiet place where she wouldn’t be disturbed by birds or worms.

With this one wish in mind, she had continued walking unsteadily on and on. But about ten days ago a great commotion had broken out around her, the Japanese began moving southwards en masse, and aeroplanes with markings she hadn’t seen before began flying around overhead.

The wolf only wanted to find a place to die as soon as possible and was not particularly startled by this. Nevertheless, the ruckus only grew daily and the sounds of human voices became ever more deafening, so she was no longer able to go peacefully on her way and was instead forced to hide in the woods by day and wait until nightfall to continue.

The wolf only wanted to find a place to die as soon as possible and was not particularly startled by this. Nevertheless, the ruckus only grew daily and the sounds of human voices became ever more deafening, so she was no longer able to go peacefully on her way and was instead forced to hide in the woods by day and wait until nightfall to continue.

At dusk on the fifth day, as the wolf came out of the woods she ran into a large group of Japanese people rushing by in a panic. The wolf cursed her own carelessness, shrinking back at the thought of being targeted by their guns, but they didn’t seem at all concerned with her as they called out to each other in shrill voices and, ignoring the wails of the children among them, hastened on their way.

The wolf had always warned the younger members of the pack that groups of Japanese were generally soldiers, most of whom were good marksmen, so they should never go near them, but this group seemed a bit different. They didn’t smell of leather or look in the slightest menacing. In fact, most of them appeared to be women and children.

Instinctively the wolf followed them. She might be on the verge of death, but she was still hungry. And there was nothing tastier than a human child, she thought, recalling how as a young wolf she had led her own cubs raiding human settlements. She followed stealthily after the group thinking that she would follow their scent for as long as it took. Even if they noticed her it wouldn’t matter, for sooner or later they would tire and squat down for a rest, and that would be her opportunity.

But the humans just carried on and on, and showed no signs of stopping even when she thought it was about time they should be getting tired. And she herself was exhausted. However, she was determined that this should be her last hunt, so however unsteady she felt, she doggedly followed after them. And just before dawn they came abruptly to a halt, a hush fell over them, and they lay down flat on the ground as if in fear of something.

The wolf took a drink from a small stream, then caught two field mice to appease her hunger. She had just started running as hard as she could to catch up with the group again when she suddenly caught sight of something red in the grass.”

Not far away was a Manchu village. The humans consulted amongst themselves, and then an old man stood up and went towards the village. As it grew light and the group became visible, the old wolf could see that, as she had thought, most of them were women and children, accompanied only by a few old men. All carried backpacks and water bottles, and had evidently been walking a long time for they all looked completely worn out, and now and then a child could be heard sobbing.

Finally the old man returned accompanied by three Manchu. She didn’t know what they were talking about, but the Japanese crowded around them, their heads bowed in supplication. Just ten days earlier, this would have been unthinkable of the haughty Japanese. They had always yelled at Manchu, Koreans and White Russians as if they owned the place!

It seemed they were exchanging goods for food, and after a long discussion the group again dragged themselves on their way, their bodies heavy after the short rest. Even the voices of the mothers scolding their grizzling children sounded pitiful, as though they themselves were wailing.

Thirsty, the wolf took a drink from a small stream, then caught two field mice to appease her hunger. She had just started running as hard as she could to catch up with the group again when she suddenly caught sight of something red in the grass. Pricking up her ears, she could hear a hoarse voice crying. It didn’t immediately occur to her that it might be a human child, but as she cautiously approached she saw a small girl tottering through the grass.

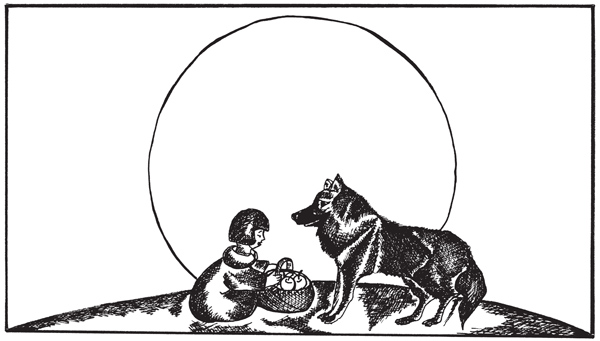

The only reason she didn’t pounce on the girl and gobble her up right away was that the edge had been taken off her hunger by those two field mice. And then she was quite taken aback when the little girl showed absolutely no fear upon seeing her, but instead called out “Belle!” and flung her arms happily around her neck.

The girl stroked the wolf’s neck and back, sobbing, “Where’s Mama, Belle? Go find her for me!” The wolf didn’t understand what she was saying, but the girl clearly thought that she was a friend and so she submitted to her, thinking how odd it was for a human to be so unafraid of a wolf.

The little girl didn’t smell of the things the wolf hated most, leather and gunpowder, but instead was permeated with the scent of milk. This brought back memories of all the cubs that, not so long ago, she herself had given birth to and raised. Come to think of it, the little girl’s sobbing voice was not unlike the wheedling cries of a newborn wolf cub.

Before the wolf realized what she was doing, she was cradling the little girl between her front paws, just as she had done with her own cubs, and was licking her face and hands, which still smelt of her mother’s milk. The little girl snuggled up to her. Now and then she called loudly, “Mama!”, but her only answer was the sound of the wind crossing the wide open plain. She began sobbing again, but when the wolf licked away her tears she became ticklish and wriggled.

Before the wolf realized what she was doing, she was cradling the little girl between her front paws, just as she had done with her own cubs, and was licking her face and hands, which still smelt of her mother’s milk. The little girl snuggled up to her. Now and then she called loudly, “Mama!”, but her only answer was the sound of the wind crossing the wide open plain. She began sobbing again, but when the wolf licked away her tears she became ticklish and wriggled.

When the wolf drank water, the little girl copied her, getting down on her hands and knees and drinking noisily. Then, feeling hungry, she took out some stale bread from her basket to munch on, first picking out the little sugar candy balls in it to give to the wolf. Sugar candy was not at all what the wolf was used to, but she tried licking it and, finding it quite tasty, rolled it around in her toothless mouth. She even began to feel renewed strength welling up in her flagging body.

“Belle, where do you think Mama went?” the little girl asked, and the wolf tilted her head inquisitively. It was the first time she’d ever heard of humans leaving a little girl alone in such a wilderness.

The little girl’s name was Kiku. Kiku had been born in a big city in the north, where her father had been the director of a photographic studio. Japanese working in Manchuria often used to send photographs to their families back home, and soldiers too came to be photographed, so the business thrived and Kiku, her two elder brothers and their German Shepherd Belle wanted for nothing. But in January that year the call-up papers arrived for her father, even though he was already in his forties, and in no time at all he was enlisted.

Their town, which had been relatively quiet even while the war was on, suddenly saw massive movements of troops. With Japan’s defences in the south under increasing pressure, the Kwantung Army, which prided itself on being Japan’s military elite, were being brought in as reinforcements. Kiku’s mother and her family didn’t know this, however. They all still believed that the northern defences were impenetrable, even if the Soviets had revoked the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact.

By the time the Soviet forces attacked in overwhelming numbers on 6th August, the Kwantung Army was a mere shadow of its former self and made up only of older, raw recruits like Kiku’s father, while their artillery and tanks had all been sent to defend Okinawa. The Japanese population quickly evacuated and fled southwards in what amounted to a stampede. The only option left to them was to travel overland, hoping that if they could just manage to reach Korea they would be saved.

The families of the military elite and the top executives of major Japanese firms in Manchuria had shrewdly assessed the situation before the Soviet invasion and had already left in a specially chartered train. The ordinary citizens had been left behind with no guarantees, and fled with just the clothes on their backs and whatever food they could carry, although at least to begin with they were able to take trains.

As they pulled into one station, they heard soldiers shouting, ‘All off the train! This train is stopping here.’ There was nothing for it but to obey the order and continue their journey on foot, with only the train tracks to guide them southwards to Korea.”

Kiku boarded a freight train with her mother and brothers in high spirits, having forgotten in all the excitement that they had come without Belle. She could feel the movement of the train through the rush matting, and she and her brothers imitated its clickety-clack until hushed by the grown-ups, who all seemed on edge. Now and then the train stopped, before slowly setting off again. They could hear the sound of explosions in the distance, and eventually Kiku too felt the heavy atmosphere in the carriage.

They were only given a little water to drink now and then, since they couldn’t go outside to pee, and nobody knew when they would next be able to get hold of more supplies. Seated on the hard floor, leaning against her mother’s knees, Kiku’s bottom hurt. But at least they were on the train.

As they pulled into one station, they heard soldiers shouting, “All off the train! This train is stopping here.” There was nothing for it but to obey the order and continue their journey on foot, with only the train tracks to guide them southwards to Korea. The group of women and children now set off at a snail’s pace along the same route that until not so long ago the Asia Express had travelled at a speed of 120 kph.

Their journey was tougher than they had ever imagined possible. Being so weak they would easily fall prey to bandits, and the Manchu seemed to know that Japan had lost for they no longer felt the need to show them any kindness. They had to give up their wristwatches in exchange for water, and when they pleaded to be allowed to spend the night in a storage shed, they were flatly refused.

They cooked by night to avoid any smoke being spotted by the enemy during the day, and drew their drinking water from a stream. Eventually some of them started falling ill. As long as they could walk, everybody rallied together, but if they collapsed then nobody had the strength to help them up again. Whenever they sensed that bandits were around they all held their breath, and if a baby started crying at that moment they had to cover its mouth to silence it, even at the risk of smothering it.

Then, by a stroke of bad luck, Kiku came down with measles. Her mother noticed she had a fever but there were no medicines, and so she hoisted her onto her back and carried on walking. When red spots began appearing on her white skin, however, her mother knew it was hopeless. After all, there were so many small children in the group, and Kiku might give it to all of them. Her mother did her best to conceal them, but their elderly leader grew concerned about how listless Kiku had become, and the moment he saw her red spots he took her mother to one side.

She already knew what he was going to say. “It’s awful, but we’ll just have to leave her behind. She’s not going to get better, anyway. If you really want to stay with her, then I’m afraid I will have to ask you to leave the group,” he told her, his face expressionless. It was the obvious thing to do.

If she took her three children and left the group, the entire family would probably perish. She considered having her two sons continue with the group while she stayed behind with Kiku, but they were only eight and six years old and still needed their mother too. She wept bitterly, but eventually decided that she would just have to abandon Kiku, who was now delirious with fever. That was the only way. She breastfed her and filled a basket with stale bread, then waited for the next rest stop to furtively place her, fast asleep, in the long grass.

She prayed that she might be taken in by some compassionate being; perhaps someone from a nearby Manchu village would hear her crying. Doing her best to convince herself of this, she returned to the group and, holding her two sons by the hand, resumed the trek southwards. When the elder boy asked, “Where’s Kiku?” she told him, “A kind old lady is looking after her because she’s so cute.”

When Kiku woke up she was taken aback to find herself all alone. Nevertheless, she felt reassured to see Belle, whom she’d thought they had left behind, at her side looking puzzled. As long as she was with Belle, she would definitely be able to find her way home – after all, Belle often used to disappear off somewhere and they would all worry about her, but she always came home.

That night the wolf held Kiku close to her until she fell asleep, and the next day she put her on her back and set off northwards at a trot. To begin with she felt she’d been saddled with an annoying burden, and didn’t know what to do. At this rate, she’d never find a place where she could die in peace. But the child seemed unwell and was completely dependent on her, and she couldn’t bring herself to abandon her.

Maybe it was the effect of the sugar candy Kiku had given her, but she decided to summon the energy to return to the pack. The lively young pack members would all take turns to bring food and look after them, and in their care even this sickly child was bound to grow strong. With the renewed faith of a mother wolf, she forced her shaky legs onward step by step, and at length came to the battlefield where the volunteer corps were desperately putting up a resistance against the Soviet forces in the hope of gaining a little more time for their families fleeing southwards.

At last quiet reigned once more. The 15th of August in Manchuria was a cloudless day with clear blue skies.

They left the sorghum field to find Japanese corpses scattered everywhere. They had just one more mountain to cross before they would reach the valley where the wolf’s pack lived. Even as the old wolf resented the curious turn of events that had disrupted her search for a peaceful place to die, ever since she had decided to take Kiku to the pack in the hope they would look after her, she had begun to lament keenly the fact of her own old age. But how heartless those humans were! Her own pack would never abandon a cub, whatever the circumstances.

They left the sorghum field to find Japanese corpses scattered everywhere. They had just one more mountain to cross before they would reach the valley where the wolf’s pack lived. Even as the old wolf resented the curious turn of events that had disrupted her search for a peaceful place to die, ever since she had decided to take Kiku to the pack in the hope they would look after her, she had begun to lament keenly the fact of her own old age. But how heartless those humans were! Her own pack would never abandon a cub, whatever the circumstances.

Eventually Kiku’s fever grew worse and she couldn’t hold onto the wolf’s back any longer. The wolf sank her few remaining teeth into the baggy trousers covering her limp body, braced her neck to avoid dragging her and staggered along northwards. Just as she came to the foot of the mountain, a human caught sight of her: “Hey, a wolf’s making off with a child!” He took out his gun to shoot her, but she lacked the strength to run and breathed her last trying to protect Kiku with her own body.

The man was surprised to find not a single bite mark on the girl’s body, now quite cold. He buried her small body then and there, leaving the old she-wolf exposed to the elements at her graveside, from where, even reduced to bones, she kept watch over Kiku.

From The Whale That Fell in Love with a Submarine, translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori. Illustrations by Mika Provata-Carlone.

Akiyuki Nosaka’s adoptive parents were killed in the Allied firebombing of Kobe, Japan in 1945, and at age fourteen he fled with his younger sister to an evacuation camp, where she starved to death. This experience led him to write Grave of the Fireflies, later made into an internationally acclaimed animated film, as well as The Whale That Fell in Love with a Submarine. Nosaka is well known in Japan as an essayist, lyricist, singer, politician and TV presenter. He has written nearly a hundred works of fiction and non-fiction, and continues to write columns for newspapers and magazines. The Whale That Fell in Love with a Submarine is published by Pushkin Children’s Books. Read more.

Ginny Tapley Takemori studied Japanese at the universities of SOAS (London), Waseda (Tokyo) and Sheffield, and now lives in rural Japan. She has translated a dozen or so early modern and contemporary Japanese authors, and her most recent publications include From the Fatherland with Love by Ryū Murakami (with co-translators Ralph McCarthy and Charles de Wolf) and Puppet Master by Miyuki Miyabe.

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

Read her introduction to The Whale That Fell in Love with a Submarine for Bookanista.