Shouting at a river

by Brett Marie

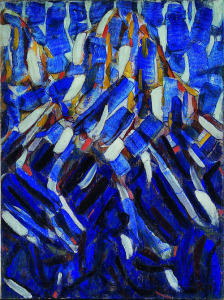

Abstraction (the Blue Mountain) by Christian Rohlfs, 1912. Museum Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf / Wikimedia Commons

Standing over a bassinet in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit in the early hours of Christmas Eve, 2002, I contemplated what the hell my first act as a father should be. My Miss Marie had been dragged into the world, with suction, only a few minutes before, and after flunking one Apgar test and remaining a stubborn purple even after they got her airway cleared, she was in the dim, eerily quiet NICU for additional treatment and observation. The nurses milling around my daughter’s station tolerated my presence, but I could tell I was an obstacle. Besides, I had to get back to my wife, whom we’d left, stunned and exhausted, alone with a nurse in the delivery room downstairs. I had to think fast, and find a way to transmit to my unwell little girl the feelings of desperate love that had built up like an electric charge in my brain.

And what was it that came to me? What did the trick? This:

“You are my sunshine, my only sunshine,

You make me happy when skies are grey,

You’ll never know, dear, how much I love you,

Please don’t take my sunshine away.”

That song carried my message, to her, and back to me. Having passed that vibration to my girl, I could leave her in the capable hands of the NICU knowing that, in some very real way, I’d shown her my love.

Partly, this was natural: I was, and still am, a musician. Of course I would resort to a song to soothe my child, just as I would reach for a guitar in trying times, to work my frustrations out through my fingers. But in the years since Miss Marie’s birth, as I’ve taken to picking up the pen as often as the guitar, something about that otherwise beautiful memory has nagged at me. As much as I cherish that memory, these days it comes to my mind with the voice of my fiction-writer self in the background, sneering at the musician in me: You have it so easy!

Our instincts tell us, rightly, that the rhythms and tonal shifts in a piece of music will reach a person on a primal level, independent of rational thought.”

Here’s what bugs the writer in me: It’s not just because of my musical background that I chose to sing to my baby. Any parent with a voice-box, facing any infant with a pair of ears, would do what I did. Our instincts tell us, rightly, that the rhythms and tonal shifts in a piece of music will reach a person on a primal level, independent of rational thought. A newborn opens her eyes to external light for the first time, having had months of practice hearing her mother’s surroundings through a poorly-soundproofed uterine wall. Even before her ears have formed, her earliest sensations come from vibrations, the essential building block to all music. And from the first, all of these vibrations have for accompaniment the subtle but constant rhythm of her own heart. Music reaches a child because it’s already familiar; it’s just an amplification, a variation, on something that’s always been there for her.

An artist armed with an instrument – or even with only her own voice – enjoys a physical advantage over one with only pen and ink. Her creations vibrate not only into the brain but also into the body. Turn up their volume and a deaf person can feel them. Sound can break up kidney stones on a microscopic level; on a larger scale it can cause an avalanche. The written word can only imply the possibilities of sound. Our tools for cranking up the volume? Italics. ALL CAPS. UNDERLINES. EXCLAMATION MARKS!! (Tell you what: go and find a snowy peak somewhere. Hold up a page with your loudest shouted dialogue written on it. See what happens. I’ll even stand beside you.)

As a musician I can gather sounds, separate them into notes, arrange them into melodies and set them to rhythms. These arrangements hit the ears, the skin, the nerves, the heart, without the brain having to interpret a single word. By contrast, any story I write must occupy itself exclusively with the brain, forcing it into somersaults to understand my syntax, retain the elements of my plot, and imagine my characters’ appearances and motivations. The brain is a barrier: my words must do all of these things, and hold its interest, before it will let me through to the heart.

I think we all recognise music’s power. Our colloquialisms confirm that. When we find an idea appealing, we say it resonates with us, it strikes a chord. If a political party fails to sway us with an argument, they have the words, but not the music. Forget these expressions: let the voices of our generation be blunt about it. Rapper Kanye West has proclaimed himself “a proud non-reader of books”, while rock ‘n’ roll’s resident curmudgeon Noel Gallagher has publicly mocked the idea of reading something that “isn’t fucking true”. And then there’s this nugget I once came across by rock writer Paul Williams, who may have unwittingly given the best illustration of music’s superiority when describing the act of listening to the Rolling Stones’ rocker ‘All Down the Line’: “And then the guitars and, uh, I’m a very happy kid. Grinning. With my headphones on. I understand the universe. Tell you about it later.” He’s feeling the same thing that gets me misty-eyed at the last chorus of Three Dog Night’s ‘Never Been to Spain’, which climaxes with the line “In Oklahoma, not Arizona, what does it matter?”

I arrange sequences of symbols which my reader will interpret as words. Most of these words have no emotional weight on their own; a huge chunk of them I can find in the manual for my lawnmower.”

It’s easy for my writer-self to feel jealous when I look at the tools I have with which to attempt to match a musician’s arsenal. In front of me I have a blank page. Onto this I arrange sequences of symbols which my reader will interpret as words. Most of these words have no emotional weight on their own; a huge chunk of them I can find in the manual for my lawnmower. I can’t depend on a spoken voice to lend them any special character; the vast majority of my audience will consume them visually, in silence. Absent the background colours a musician can play tricks with – the shift from a major to a minor chord, the slight slowdown of the tempo as we crescendo into a chorus – I can only ask the reader’s brain to pretty-please perceive something according to my directions to achieve an emotional response. At best this seems like a tall order; on a bad day, it feels akin to shouting at a river to flow the other way.

Am I alone in my despair? I don’t know. I took the concept to my friend John, better known as novelist and short-story wizard J. Robert Lennon. I knew John would have some insight on the subject; he has a number of recordings under his belt, on his own and with the Starry Mountain Sweetheart Band. John didn’t disappoint, but his reply to me was the email equivalent of a shrug. He wasn’t worried about the advantages of one form over the other: “I don’t really think of it that way,” he wrote. “Like fiction writing, music is a mysterious compulsion for me. I’m not trying to elicit a particular response, except maybe dancing? I just feel like making it and I do, and it feels good.” When I asked him if he ever drew from his musical knowledge to create a certain effect in writing, he told me about a rock novel he started and then abandoned, “at least for the time being”. Then he gave me a pearl to add to my list of defeatist statements: “Whenever I try to write about music, I get bored and wish I were actually playing music.”

I should say that John is absolutely right. His words reveal an artist comfortable with his talents and happy to have both music and fiction writing to use as he pleases. And if I find his answers underwhelming, it’s my own fault; I didn’t let on to John how urgent this issue is to me, and I never gave a hint of why.

To get at the root of my frustration, we have to come back to Miss Marie. Her story doesn’t end in the NICU. My girl pulled through, and thrives to this day, but from the moment she drew breath, she was not the girl my wife and I had been expecting. It’s a challenge, to say the least, to get this child to achieve what comes naturally for other boys and girls her age. At twelve, she can pull on her socks but not tie her shoes. She can eat with a spoon or fork, but needs help brushing her teeth. She can articulate her basic needs and desires, but struggles to put across her thoughts in a sentence longer than four words. And though I’m told she’s reading phonetically at an above-average level for her condition, she still lags behind most kids her age.

But put my girl in front of a piano, and she’ll make you stop worrying about what she can’t do. Having listened obsessively to music since before she was born (she enjoyed her mother’s Jimi Hendrix kick in utero), Miss Marie has a great feel for a pop song. Her talents for music are many: a keen memory for finger placement and chord changes, perfect pitch (sing her a line in C major, and she’ll jump at the chord without prompting), a knack for singing harmony (which is more than I can say for most of the bandmates I’ve had). Nothing in this world gives me more joy than to pick up a guitar and play along with her. And though she has some trouble walking and running, she will shake a tail-feather on occasion, if the mood strikes her.

I would do anything to reach this little person with my writing the way I can with music. And it occurred to me that I must not be the only writer who has had to confront this sort of reality. Nick Hornby used his love of music to great effect in his novels High Fidelity and Juliet, Naked; he has also been admirably outspoken as the father of a son with autism. I reached out to Nick, asking if it frustrated him that his writing talent might be useless in connecting with his son Danny. Surely, I thought, he would agree with me, that though our children live with different conditions, we had this unfulfilled yearning in common.

I got another shrug in reply. Nick wrote back that he was with Danny at the moment: “He’s just shut himself in his bedroom, and he’s listening to Exodus by Bob Marley. I don’t know for sure that he likes it, but he asked for music and I often play him Marley on Saturday mornings.” Nick showed little of the despair I’d assumed we shared: “I suppose a long time ago, when he was first diagnosed, it may have crossed my mind that he would never read anything I wrote, but I haven’t thought about it in a while.”

Besides, he pointed out, “your question presupposes an idea that he would get something out of my work if he were neurotypical. Recently my middle child, nearly thirteen, picked up About a Boy because my wife, his mother, told him he’d enjoy it. But he hates reading, really, and we have to get on his case to make him read even fifteen minutes a day. He’s smart and capable but he’d rather be on his Xbox. So I’m yelling at him to read my book and he rolls his eyes and grumbles.” All things considered, he wrote, “Danny’s autistic indifference to my writing seems like the kinder filial response!”

This need of mine to connect with Miss Marie may have been egotistical in its first vague pangs, but it sharpened into something different as I completed my first novel… a big part of it became a sort of love letter to her.”

Just like John before him, Nick had shown no qualms about the limitations of his medium. And of course I’m happy for him, that he has the wisdom to accept things as they are. The self-effacing humility of his words left me wondering if my writerly angst springs solely from my ego. But there’s more to it than that. This need of mine to connect with Miss Marie may have been egotistical in its first vague pangs, but it sharpened into something different as I completed my first novel. There’s a character in that book who has a lot in common with my girl, and though the story is about a lot of things, a big part of it became a sort of love letter to her. On some level, I wanted my story to tell her how much I love her, and how happy I am to have her just the way she is. But she’s a long way from communicating at the level my prose demands, and by all accounts it’s unlikely that she’ll ever get there. And so the one person I want most for my message to reach may be the one person in my life who won’t get it.

Of course, I can still try. Language is difficult for Miss Marie, but it’s not impossible. I can keep working with her, helping with her speech therapy, trying to break down increasingly abstract concepts into their more concrete components for her to grasp, searching for the simple words that will make it through her brain and into her heart. And it’s funny: all that casting about, it’s what I’m doing when I write anyway. It’s what I enjoy, and it’s also what I enjoy about reading. John writes: “The abstraction of language is much less tyrannical than other mediums; a red pickup truck, let’s say, looks pretty much the same for everyone who sees it, but a verbal description of a red pickup truck evokes different images for each reader. Language is less precise, in other words, and requires imaginative participation on the reader’s part in order to work. Consciousness isn’t something you can pin down; it’s protean, it’s specific to its bearer. And so it likes the loosey-goosey, exploratory nature of language.”

Of course, I can still try. Language is difficult for Miss Marie, but it’s not impossible. I can keep working with her, helping with her speech therapy, trying to break down increasingly abstract concepts into their more concrete components for her to grasp, searching for the simple words that will make it through her brain and into her heart. And it’s funny: all that casting about, it’s what I’m doing when I write anyway. It’s what I enjoy, and it’s also what I enjoy about reading. John writes: “The abstraction of language is much less tyrannical than other mediums; a red pickup truck, let’s say, looks pretty much the same for everyone who sees it, but a verbal description of a red pickup truck evokes different images for each reader. Language is less precise, in other words, and requires imaginative participation on the reader’s part in order to work. Consciousness isn’t something you can pin down; it’s protean, it’s specific to its bearer. And so it likes the loosey-goosey, exploratory nature of language.”

I find pleasure after slaving over a crucial passage, when I read it back and feel it do to me exactly what I wanted it to do. I get that same pleasure when I speak to Miss Marie, when I see her face light up with comprehension. I got it last week when she said to me, “Daddy, take my shoes off, please.” We look for meaning; we find it. The pleasure is the same, whichever way it comes.

So here I find myself in the present day, pouring my sweat into that tricky form of self-expression, fiction-writing. I worry about plot inconsistencies, obsess over character development, agonise over word choices and rack up hours typing in, deleting and retyping commas and semicolons. My work gets put out, it gets attention, and I get a good deal of satisfaction when I learn that it’s struck a chord with a reader. Maybe someday that reader will be my girl (I won’t stop hoping yet). Maybe I’ll break down my novel, tell its story to her like one of her picture-book fairy tales, and maybe I’ll get an “I love you, too, Daddy” for my trouble. In the meantime, my writer-self will have to grin and bear the sight of my girl’s open-mouthed smile when I or my wife pick up a guitar and play. And he can be proud of the words he wrote to a song named after her:

“And I don’t mind if you don’t understand,

Life’s been kind, though it’s not the way I planned.”

I think that line ought to reach her soon. Until then, on a good day, at least it’ll get her dancing.

Brett Marie, also known as Mat Treiber, grew up in Montreal with an American father and a British mother and currently lives in Herefordshire with his wife, Greenwich Village singer/songwriter Roxanne Fontana and their daughter. Fronting the Mat Treiber Group, he has played energetic, bluesy rock ‘n’ roll in venues from Los Angeles to London. His other great passion, writing fiction, is displayed in short stories such as ‘Sex Education’, ‘The Squeegee Man’ and ‘Black Dress’. These and other works have appeared in publications including The New Plains Review, The Impressment Gang and Bookanista. He recently completed his first novel The Upsetter Blog.

Brett Marie, also known as Mat Treiber, grew up in Montreal with an American father and a British mother and currently lives in Herefordshire with his wife, Greenwich Village singer/songwriter Roxanne Fontana and their daughter. Fronting the Mat Treiber Group, he has played energetic, bluesy rock ‘n’ roll in venues from Los Angeles to London. His other great passion, writing fiction, is displayed in short stories such as ‘Sex Education’, ‘The Squeegee Man’ and ‘Black Dress’. These and other works have appeared in publications including The New Plains Review, The Impressment Gang and Bookanista. He recently completed his first novel The Upsetter Blog.

Facebook: Brett Marie

@brettmarie1979

bookanista.com/author/brett-marie/