I’ll sing when you sleep

by Krishna MonteiroAnd so too might cocks, falcons, and other birds of

prey, which have been forced into warlike battle at

the hands of man, be armed like knights.

Treatise on falconry and other arts, 1386

Look at Me! (2019) by Sandra Malan-Bowles

He steps into the ring and notes with apprehension that his opponent has spurs curved like Moorish swords. His armour, sharp, gleaming, resilient, covers the whole of his head and lower limbs. He thinks of himself, in his own armour. He also thinks about why the hands in the grandstand are so restless: they’re raising clouds of dust, flailing and stabbing the air, in no way recalling the ones that, in days past, backlit by flames, brought black birds to life on the screen of a white wall. Hands have always intrigued him. He thinks: “Besides flying as birds with shadow feathers, hands can also caw like crows. They must be related.” The calls from the stands increase around him; the other provokes him, waving his cape, his multicolour tail, right and left. But he won’t be fooled by these tricks. He keeps up with his double by swinging his neck back and forth, protecting his torso, crossing swords, raising his right wing like a shield or barrier extended well above his head. “Watch the head,” Conceição was saying. “If the needle pricks it, our effort will be for nothing.” He recalls how Conceição and the boy carefully poked the needle around his skull to avoid injuring his spine while cracking open the shell and the casing he was floating in. Immersed, he could see how the entirety of what he knew was about to splinter, come apart in pieces. The outer covering shattered. The fluid drained out. His first breath pierced his lungs. He steadied his wobbly legs for the first time and felt himself nestled between the palms of two hands. And they lifted him up to the woman with silvery-grey hair-feathers, they led him – and everything was aglow – to the tenderness reflected on Conceição’s face. He thinks: “How smooth the boy’s hands were back then.” In the arena, the crowd of hands grips the fence around him and his opponent, showering the ground with green papers like leaves falling from trees. The other stares him down, claws angrily at the earth, brandishes his beak in search of an opening to deal the first blow. Behind the prostheses and metal protection that sheathe his head, however, he wears an oddly lost expression. The chatter of the hands gets louder and louder; he follows his double closely and mirrors his moves exactly. And before he can think about trying to retreat, he feels the pressure of two palms on his underbelly and finds himself suddenly hoisted into the space, flying against his will toward the daggers and blades. One. Two. Three. He backs away, panting after the fourth thrust. He wipes his eyes, becomes aware that a thick ruby-red strand trickles from his throat. He stares at the other’s feathers, which reveal a collar of blood just like his. “She could accept him or she could kill him,” Conceição was saying. “He’s from another mother, no one knows how he’ll turn out.” Conceição and the boy placed him on the ground; the land he trod seemed to stretch forever. Behind silver wire mesh, threaded to heights beyond his view, a pair of wings ruffled as they sensed his arrival. If he had known the exact term to describe their tones and colours, he would have said “mother-of-pearl.” But he wouldn’t learn this until later. Alert, suspicious, fearless, the mother-of-pearl wings cocked in a defensive stance. Unaware of the treacherous boundary he was venturing over, he jumped across; the wings stiffened, relaxing and opening a split second later, nestling him into a petal-like texture. A thick and welcoming darkness embraced him, and he wondered if he was back inside the shell from which the woman and the boy had ousted him. But there, all was liquid, and here only an air of familiarity. Furthermore, the strange round beings covered in golden-yellow fuzz that clustered around him didn’t exist there. In the dark, he saw himself surrounded by tiny, curious, twinkling eyes: eyes different in every way from the two fiery sockets that – he knows – want to destroy him, at all costs, this very afternoon. The other wipes away with his wing tips the red that spurts from his breast, takes a breath, sharpens his spurs on the ground. And, reflexively examining his double and his sad, trembling figure, he realises that there can be only one outcome. Behind his opponent’s back, the hands are increasing and coming closer. Behind him, an insurmountable wall of hands goes up: thick, calloused, unfeeling. “Sooner or later, they’re going to push me,” he thinks. So he beats them to the punch.

He senses that the other is already pulling away, his face livid, frightened. With his right foot, he latches onto him, and wisely wielding his left spur makes a series of precise incisions in his belly. One. Two. Three.”

He lands on the other like a barb, driving in the points of his spurs (which are curved like Moorish swords) as deep as possible. He hears a dry snap and feels something splitting. He does as he learned, as it was written: the right wing is the shield that deflects the blows; the left is the sword that swishes; and from the sky and from the earth and from all directions his body will thunder, like a vengeful hailstorm: that’s how it was written. He senses that the other is already pulling away, his face livid, frightened. With his right foot, he latches onto him, and wisely wielding his left spur makes a series of precise incisions in his belly. One. Two. Three. He hears, can hear, something splitting. Conceição was counting and splitting the ears of corn, the kernels dropping down on him and the others, the colour of the corn blending with that of their bodies, their mouths gathering the feed being scattered on the ground and in the grass. Circling protectively around them, scratching and foraging, were the mother-of-pearl wings. And when the sun was finally setting, when his siblings were retiring behind the screen of silver wires and the measured breathing of their bodies was all that persisted in the night, that’s when he saw them appear, take flight: birds with shadow feathers, gliding over the white walls of the kitchen. Conceição’s hands fluttered before the blaze of the wood stove. They swooped down over the house and neighbourhood audiences piled onto benches and tables, watching wide-eyed the movements of that theatre of black birds.

On the ground, his cold feet. In front of him, his exhausted, drained enemy. The colours of the world are hazy, his vision blurs, and for a moment he thinks he’s fighting against two or three. But he perceives that his double, rather than attacking, now leans on him for support, as a crutch, and he too allows himself to sink against the other, both turning on an imaginary axis, stumbling and coming undone in a pool of their very essence. “Nothing to see here,” he says to his reflection in the liquid. “Nothing to see here,” Conceição was saying. The body lay stretched out in the cauldron, its back cut by a gash through which the last breath would escape. Rubbing its skin in a ruthless rhythm, Conceição’s fingers plucked the feathers and tossed them into the air. The light crossed with them before they landed; he recognised their colour, their texture; he searched for what they were called and said to himself: “mother-of-pearl.” By then he had learned and knew their name. “Nothing to see here,” Conceição said to the boy. “This kitchen is overrun.” The next few afternoons would bring the cyclical moods of the winds: bitterly cold, sluggish, on fire. The windmill spun, the seasons coming one after another, and turning his back on the woman and her hands, he felt capable of further strides. The borders of the world shrank. The screen of silver wires was closer. One day, to his surprise, he found himself rise into the air: it was the flapping of his own wings. And landing on a wooden beam, he proudly admired the two limbs, covered in pointed, multicoloured feathers.

The hands shout and squeeze together in the arena. Then the lunge, the spring of two hands, hot like flames, and he’s surprised, captured between the knots of that web of fingers… his double turns pale and twitches.”

His double looks at him. The way Conceição looked at him. His double circles him. The way she circled him, from afar. When she’d bring the shower of corn. When she’d sneak up close. Licking his wounds, his double glances over at him. Was he, too, burdened by memory? The body in the cauldron, the trampled feathers: remembering them, he distanced himself, flew far from Conceição. But she was persistent, entering his domain, opening the gate door, sitting in a corner on the straw and getting caught up in her thoughts, fencing him in with the weight of her gaze. His double limps, his right foot crushed. The hands shout and squeeze together in the arena. Then the lunge, the spring of two hands, hot like flames, and he’s surprised, captured between the knots of that web of fingers: he spotted a raw patch on Conceição’s palm and pecked at it repeatedly, trying futilely to free himself (his double turns pale and twitches).

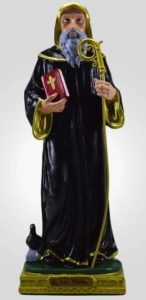

They entered the kitchen, he a metre and a half off the ground. From above, caged between the fingers and palms that held him, he saw a line-up of things he couldn’t name: coverings, handmade objects, hanging things. His chest throbbed, pounded, and perhaps because they felt and feared that beat, the two hands began to lower him. They set him down, offered him a gourd full of golden grain; tasting it, he realised it was the same stuff that would rain down on him and his siblings in the mornings and evenings. He devoured the corn, feeling the caress of Conceição’s fingers rubbing the feathers on his back. “Nothing to see here,” she said to the boy, who was already hovering. “We want to be alone.” Polishing off the gourd, he felt the hands pick him up again. And there was Conceição, showing, telling and teaching names, unveiling and cataloguing the world, everything aglow: the image of St Benedict, patron saint of the kitchen, behind whom the matches were hidden; the water cooler, with the battered tin cup beside it; embroidered dish towels; green tiles that came from the other side of the ocean; the wood stove, breathing heat and giving off light; and him – from that moment on – tracking paths opened by the woman with the silvery-grey feather-hair, following her footsteps from dawn to dusk, every day.

He knows he too is injured, but years in the ring have taught him that, to some extent – tenuous, and precise identification of which distinguished the great fighters – there was a comeback and cure for any wound.”

He tells himself that if his double continues to wander unwisely in front of him, guard down, wings bent, without purpose or direction, it will only be a matter of time until everything comes to an end. He decides to wait. The other’s blood flows and soaks the sand. “At this rate, he’ll go down in no time,” he thinks. Better to wait. He knows he too is injured, but years in the ring have taught him that, to some extent – tenuous, and precise identification of which distinguished the great fighters – there was a comeback and cure for any wound. He looks at the other’s trail of blood. He calculates. Behind his double’s head, clouds travel across the sky, frame his profile against a vast blue background. It’s as if the shapes of the clouds, their designs and contours, gather and envelop that head like a halo, foretelling a sacrifice. But one of the cumulonimbus clouds darkens, takes on a sharp look; and before he can take a breath, he feels a stab like a red-hot poker to his belly. After being lifted and flung to the ground, after getting up and seeing that the other is laughing a suicidal laugh, after finding out just how foreboding the clouds really are and that the sand is now soaked with his own blood, he deduces that he too has crossed the point of no return.

The boy would scream in the middle of the night. When he was delivered as a baby in a basket and Conceição tucked him between the same sheets she slept in, his cry was stifled by dripping sugar water between his gritting, grinding teeth. However, over time, with the spin of the windmill, the wails of the one who had grown and moved into the adjacent bed intensified, resounding in their full terror at four in the morning like the plea of a creature imprisoned in something it couldn’t comprehend. The statue at the head of the bed did no good – “It’s to protect you,” Conceição had said upon placing it there; the prayers, blessings, brewing of sage did nothing, for the screams persisted, echoed, woke up the whole house. Until one night, running her hand through that hair awash in cold sweat, Conceição pulled out of who knows where a forgotten song, the last verse of which went: “I’ll sing when you sleep.” Alone with the boy between walls laden with memories (only the two were left, the others had gone), she noticed that his arms unfolded and finally hung loose, that his whole body turned toward the song and he dozed off. She drew the curtain. Peered out the window. Saw that the day was breaking.

Perched outside, he heard the music too. He sensed that a light born of the night, which grew brighter behind the crests of the hills, dawned not only and increasingly on the yard, the mortar and pestle, the sugarcane grinder, but inside him, drawing out something that had always existed: a desire, an ancestral drive, a dormant tension. Something that, for mysterious reasons, itched unbearably, more and more intensely, coursing like anguish through his veins toward his throat, nearly bursting as a spasm, rapture, an unstoppable and unfulfilled wish. He gripped the perch. He puffed out his chest, felt something bloom within him. Through the window, he saw Conceição’s silhouette cradling the boy. And when the cry finally erupted and sprang from his throat, echoing over the rooftops, waking all the neighbours, he could tell that, like the woman keeping watch, his entire being seemed to affirm “I’ll sing when you sleep.” He repeated the verse at the top of his lungs. He sang. The sun came up.

Bleeding out, growing weaker amid the hysteria of the hands that doom them, the two take random swipes at one another. One by one, the pieces of their armour fall apart, tumble to the ground, and he thinks: ‘Seems like yesterday.’”

The blow strikes his double head-on. It rips off the metal covering that protects his face, causing the bronze-coloured helmet to fly far afield, as if cast to the wind. But the reaction doesn’t take long: the counterblow comes like lightning, a last-ditch effort, and there are now two bare heads, beaks stripped, bewildered eyes exposed. Bleeding out, growing weaker amid the hysteria of the hands that doom them, the two take random swipes at one another. One by one, the pieces of their armour fall apart, tumble to the ground, and he thinks: “Seems like yesterday.” On a now distant day lost in time, he followed Conceição’s steps across the kitchen floor. Bent beneath a load of firewood, she shuffled toward the stove – lighting it, blowing it, feeding it, smiling on hearing the roar of the dancing flames. She sat pensively at the foot of the fire, nibbling on corn bread, sharing it with the wings nestled in her lap. She didn’t notice the shadow, the darkness on the screen of the walls; didn’t notice the two hands, thick and calloused, rubbing together. When she sensed the boy lurking, she thought of saying to him, “Nothing to see here,” but the presence had vanished by then. And nibbling her corn bread, Conceição concluded that the cries she thought she’d heard were merely the howling wind that shook the roof and rafters.

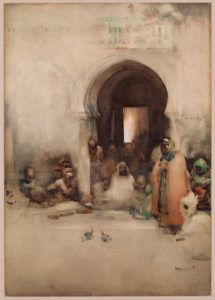

Cock Fight by Arthur Melville, 1900. Metropolitan Museum of Art

In the yard, the boy squeezed his throat, suffocating the last of the cries for help. His other hand dropped to the ground, palmed a number of shiny objects not seen before. The hand lifted one piece (long, curved, with a sharpened tip) and fitted it to his left spur: his leg now weighed him down. Unable to support the almost unbearable burden of the daggers, the sabatons on his feet, the hood on his head, which hindered movement of his neck, his body swayed and stumbled. He fell. Through the holes in the chainmail, he heard muffled laughter. He looked toward the kitchen. He wanted to call Conceição, to eat corn, to rest at the feet of the woman and St Benedict. But she didn’t hear him. She hasn’t heard him for a long time. Incapacitated, confined to a chair, Conceição’s emaciated body remains motionless, her head in a fog.

His left foot strikes the head of his double, who drops to his knees. But he hardly notices his enemy’s fall. He’s focused on a day in the distant past, a back yard, the boy’s hands: that afternoon, they bore cuts and scars that hadn’t always been there. He saw a land criss-crossed by wires, in which hands lifted him once more, but in another way: with the skill of a soldier and the thoroughness of a master armourer. He felt the young man – or who he had become – clean and polish the metal suit. He saw that the man held a clove of garlic in his palm. He accepted the offering, pecked at and swallowed it, a fire burning his belly: he noted then that an appetite had arisen in him, a certainty, an unspoken anger, a desire to fight. The leather and bronze armour was striking. Training sessions followed. In a long succession of late afternoons, skills, tricks and techniques were presented. Ways of drawing blood and resisting. The armour, perfectly melded to his neck and lower limbs, seemed to grow stronger on his flesh. Light, flexible like a second skin, adjusted with the detail and care of a goldsmith. The boy placed him in his lap. He pointed to a circle outlined in the yard. Together, they walked in that direction. The hands lowered him. Looking around, he found himself surrounded by hundreds of other hands. He stepped into the ring for the first time, and for a moment thought he stood before his own reflection. But he remained still while the being in front of him moved, flaunting his colourful tail like a war pennant. He stepped into the ring. He noted with apprehension that his opponent had spurs curved like Moorish swords.

His double is no longer breathing. And he, stepping over that motionless body, tries to walk toward the last reflection of the house and kitchen. He sees Conceição hunched beside the wood stove. The old woman trembles, turns over a log, the flames burst forth and blaze, the sun is going down. Alone, without the audience of days gone by, Conceição raises her hands into the air. And he thinks: “Nothing to see here.” But he catches a glimpse of the first of them, wings, bent shadow feathers fluttering, tracing curves on the walls. Conceição ponders her own hands. Other birds take flight: landing on the roof, on the ground, all over the place, they recall a flock of migratory birds in search of warmth. Black like crows, they caw, dance around the fire. Their shapes, as they grow, gradually cover the roof, the pots, the copper spoons, and the whitewashed bricks. They extend over coverings, handmade objects, the ocean-green of the tiles, and united as one body, suddenly merge into a whole, drop and darken, landing right on the patron saint. Night shatters the windowpanes. Covers the grass. The corn. The mortar and pestle, the sugarcane grinder. It bathes the earth, its mother-of-pearl tones. And the walls of an enclosure, quite similar to the one the woman and her son drove him out of, go up around him. Thick and dark, the fluid rises up over his legs, his back, his neck. The outlines of the yard disappear. A shadow is drawn in the darkness. The container closes, his last breath escapes from his lungs. He tries to steady his wobbly legs but he floats, and adrift, suspended in that liquid, he can still hear the sound: the spin of the windmill, its gears, its glacial blast, advancing over the land like galloping troops marching forward.

Translated from the Portuguese by Kim M. Hastings

Krishna Monteiro was born in Paraná in southern Brazil in 1973. He studied economics and completed a master’s degree in political science at the Campinas State University (Unicamp). After a brief career in journalism, he entered the Brazilian diplomatic corps. He has lived in Sudan, England and India and presently serves in the Brazilian embassy in Tanzania. In 2015, he made his authorial debut with the story collection O que não existe mais (What No Longer Exists, Tordesilhas Books), in which this story first appeared as ‘Quando dormires, cantarei’. The book, which will be published in France and Romania, was a finalist for the prestigious Jabuti Prize in 2016. His first novel, O mal de Lázaro (Lazarus’s Disease), was published by Tordesilhas Books in 2018. His short stories have been published in England, France and Mexico.

Krishna Monteiro was born in Paraná in southern Brazil in 1973. He studied economics and completed a master’s degree in political science at the Campinas State University (Unicamp). After a brief career in journalism, he entered the Brazilian diplomatic corps. He has lived in Sudan, England and India and presently serves in the Brazilian embassy in Tanzania. In 2015, he made his authorial debut with the story collection O que não existe mais (What No Longer Exists, Tordesilhas Books), in which this story first appeared as ‘Quando dormires, cantarei’. The book, which will be published in France and Romania, was a finalist for the prestigious Jabuti Prize in 2016. His first novel, O mal de Lázaro (Lazarus’s Disease), was published by Tordesilhas Books in 2018. His short stories have been published in England, France and Mexico.

Author portrait © Arit Arora

Kim M. Hastings is a freelance translator and editor based in the US. She lived in São Paulo for several years, studied Brazilian language and literature at Brown University, and holds a PhD in Spanish and Portuguese from Yale. Her translations include Edgard Telles Ribeiro’s award-winning novel His Own Man (O punho e a renda) and short fiction and author interviews published in anthologies and magazines including The Book of Rio, Words Without Borders, Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas, Two Lines, Litro, Machado de Assis and Bookanista.

Kim M. Hastings is a freelance translator and editor based in the US. She lived in São Paulo for several years, studied Brazilian language and literature at Brown University, and holds a PhD in Spanish and Portuguese from Yale. Her translations include Edgard Telles Ribeiro’s award-winning novel His Own Man (O punho e a renda) and short fiction and author interviews published in anthologies and magazines including The Book of Rio, Words Without Borders, Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas, Two Lines, Litro, Machado de Assis and Bookanista.

Read more