The Talleyrand of East Africa

by Dominic Dromgoole

“Richly entertaining.” The Times

“’Ullo, I am ze Breetish Consul.”

My startled reaction revealed my prejudice. I didn’t cover it well.

“You can’t be. You’re French!”

“Eet is a long stohry. Shall we ’ave a drink?”

We sat down. One by one the other members of the company came to join us, dressed in their evening casual best, and sat in a broad circle around this elegant, ageless man. Imported palm trees towered above us, and the heat of the day declined as a soft breeze blew in from the Red Sea. The consul spoke with a measured, steady calm, telling his own story, but also that of the statelet we were in, Djibouti. His tale was full of information, but for every five facts revealed, something in his delivery implied there were another fifteen concealed. He revealed a little about Britain here, something of France there, some US history at one moment, some projections of Chinese influence in the next. Every time he did so, he seemed to open a door on a wealth of hidden knowledge, allowing a glimpse of a glistening horde of secrets, before deftly closing the door again, leaving us hungry for more. Demure, discreet but indiscreet, gently witty, old-school charming, his performance had a mesmeric quality.

As the waves plashed gently on the artificially constructed beach, the view broken by more imported palm trees, we sat on wicker chairs on manicured phoney grass and listened to a deft and elegant lecture on the movement of power in the modern world. He threw up an exquisite cobweb, built from hints and allusions, subtle implications and wise inferences, which seemed to trap some of the mysteries of the world within its fine and glittering mesh. He was the lawyer for the hotel, for most of the government and, as his monologues spanned ever greater and finer filigree webs of influence, seemingly for most of the important people in the world. He began his career from Paris representing Djiboutian rebels fighting for independence, when their principal freedom fighters were all incarcerated. When they won, he became, at a very young age, their de facto legal representative. As is true everywhere, last year’s terrorist is often this year’s president. So our host flipped at speed from being the radical representative of the beleaguered to being the legal advisor to the government. Partially resident in Djibouti for more than thirty years, over the intervening time his influence and his connections had spread wider and wider.

***

The show in Djibouti was not great. The setting could not have been more beautiful: an open stage with the waves of the Red Sea folding in behind, the sun going down before. But it was on the edge of the hotel compound, and the pleasures of this gilded cage were wearing thin. There had been little or no marketing, and with half an hour to go there was not much sign of an audience. I wandered around the cavernous marble-ceilinged hotel foyer picking up a few lost souls looking for the show, then positioned myself behind the airport-style security at the front door to steer the few people allowed in towards our temporary theatre. Thankfully a group of students arrived to give us some contact with the locality. When we settled, there were only about 120 people – a bewildering mix of a few ex-pats, some financiers from the hotel, a smattering of Special Forces, a sprinkling of Djiboutians and the students. The posh locals seemed more interested in the table of drinks than Hamlet, and seemed a little put out they had to watch the show; the students seemed keen to sneak behind the toilet and have a smoke or snog each other. Bizarrely the Special Forces contingent seemed quite into it.

Things got decidedly odder later. Our host was keen that we join him in his home after the show. He had issued the invitation during the monologue the day before, and had rung twice to confirm it. Having enjoyed his company, many of us were keen, and he hung around afterwards, being generous with compliments, and watching as we dismantled the set. We then set out in two vans and drove to a diplomatic area near the hotel, where we found large residence after large residence, each surrounded by a high white wall, each white wall enclosing palatial emptiness. The streets were deserted. No cars, no people. On a distant hill, we saw the city of Djibouti, a tumbling metropolis of houses and life. Here there was emptiness and silence. It was all manicured and elegant in the desert night air, but felt like a zombie film before the zombies show up. We swung through heavy iron gates into our host’s residence, a cool white building set in a cool white compound. A string of buildings created a quad, on one side of which was his home, beyond his very own infinity pool, and beyond that a long private beach leading down to the sea. Paradise but again eerily empty.

Our host bounced from pillar to post with excitement. He scurried us through his home, showing us every room as if we were at the Ideal Home exhibition, pointing out with particular pride the pictures of himself with several large fish (always a danger sign), switching lights on, as if he had just moved in. He flicked the switch to illuminate the pool from underwater with the pleasure of a child showing off a toy. After he had shown us everything, he sat down and looked at us with a peculiar expectancy. As if it was our turn to start amusing him. Some odd silence gave the impression we were now supposed to burst into song, or start telling sad tales, or take our clothes off and start performing sex acts on each other.

When we eventually reached the kitchen, he said, “Aha! Let’s see what treasures we have in here,” and walked straight into a laundry cupboard.”

What he seemed completely unprepared to do was to feed us or slake our thirst. A company of actors after a show has very powerful and simple needs. Food and drink. Nothing was forthcoming. When he began another monologue on geopolitics, expecting us to all sit and look entranced, I expressed rather forcibly the idea that food and drink were a little more than necessary. He looked a little cussed, then suggested that I went with him to the kitchen. He seemed to have a hard time finding it. When we eventually reached the kitchen, he said, “Aha! Let’s see what treasures we have in here,” and walked straight into a laundry cupboard. Having located the fridge and the cellar between the two of us, I reassured him that I could take over from there and that he could return to the guests. I opened the capacious fridge to see – what else? – block after block after block of foie gras. Literally nothing else. I scoured the rest of the room for biscuits and returned to the throng with a mountain of foie gras and a few bottles of vintage champagne.

When I returned, he was entertaining everyone with a discourse about the difficulties of creating true democracy in Djibouti. With a small population with ancient regional and tribal differences, it is a delicate matter creating a system when a simple majority government can’t reflect the vested interests of each group. As has been witnessed elsewhere in the region, and not that much further afield in Iraq, a first-past-the-post system can’t guarantee a place at the table for all the different ethnic and religious entities. The result is a power-sharing arrangement with representation according to tribal numbers. This formula where everyone is given a voice seems an elegant solution, and one which he had in part authored.

He was proving persuasive and fascinating again, and the company were feeling warmer with a lump of foie gras inside them, and half a bottle of Lanson. But the strange confusion as we had arrived, and the over-excitement at our presence, had diminished his mystical authority not a little, and there was a dangerous sense of humour floating around the group. We were sitting around a marble-slab table beside the outdoor pool under the stars, and mischief was tickling the air. Our host was telling a long story about how a Spanish warship in the port had accidentally fired off a missile headed for the diplomatic zone. As he reached the moment where the missile shot off, he flung out his hands and caught Amanda square in the tit. She said nothing, he said nothing, sadly no one did, and a small titter of giggles started to play between us. He then told a long story about the arrival of something called the Kent in Djibouti. Unfortunately, he had a very peculiar way of pronouncing the word Kent. For a while we wondered if this was a product called Kent, the Duke of Kent, or just someone he didn’t like very much. It is very hard to ascertain what it was without saying ‘Keyunt’ a lot. Which didn’t reduce the hysteria of the room. Eventually, we ascertained that it was a ship called the Kent, but by this stage the room was close to hilarity. I said that it was time for us to go to bed. Everyone leapt up with alacrity.

He insisted on showing us the consulate. As we walked to it, he kept slowing down whenever he got near a picture of himself with a fish, and drawing breath ominously, before I hurried him on. The consulate was sumptuous, dripping money and power and art to the appropriate degree, but escape was becoming important. Hysteria was growing but also an eerie sense of being locked in, incarcerated in the lovelessness and deadness of power. Just as we were heading for the vans of departure, I was walking abreast with Rawiri. We heard the ever-ebullient Keith behind us saying to our host, “Tell you what, why don’t you tell us your most exciting fishing story?” Fortunately, stage management saved the day and bundled us into vans. Our hysteria was spent as we drove back through the empty streets of the diplomatic area.

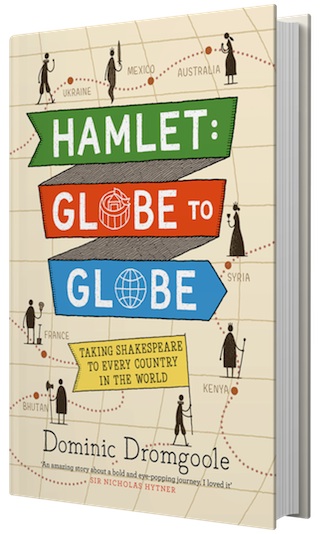

This is an edited extract from ‘Polonius by the Read Sea’ in Hamlet: Globe to Globe. Out now from Canongate.

Dominic Dromgoole was the artistic director of Shakespeare’s Globe from 2005 to 2016, and recently founded the production company Open Palm Films, where he’s working on six features and director or producer. He is the author of The Full Room: An A-Z of Contemporary Playwriting and of Will and Me: How Shakespeare Took Over My Life, which won the inaugural Sheridan Morley award. He regularly contributes to the New Statesman, the Sunday Times and other publications. Hamlet: Globe to Globe is an account of Dromgoole and the Globe players’ two-year tour that set out to perform Hamlet in every country on the planet, combined with a close reading of the play and its effects on audiences worldwide. It is published by Canongate in hardback and eBook.

Dominic Dromgoole was the artistic director of Shakespeare’s Globe from 2005 to 2016, and recently founded the production company Open Palm Films, where he’s working on six features and director or producer. He is the author of The Full Room: An A-Z of Contemporary Playwriting and of Will and Me: How Shakespeare Took Over My Life, which won the inaugural Sheridan Morley award. He regularly contributes to the New Statesman, the Sunday Times and other publications. Hamlet: Globe to Globe is an account of Dromgoole and the Globe players’ two-year tour that set out to perform Hamlet in every country on the planet, combined with a close reading of the play and its effects on audiences worldwide. It is published by Canongate in hardback and eBook.

Read more.

Author portrait © Shakespeare’s Globe