Tremors

by Manu Joseph

“Caustic, comic and determinedly controversial. And there’s a thriller lurking beneath too…” Observer

Around 7:30 am

When she returns from a long run she finds her neighbours standing almost naked in the compound. Men in morose Y-front underwear, women crouched behind parked cars or hidden inside rings formed by other women who are not bare. Through the gaps in the cordons she sees flashes of naked thighs, waists, backs. It is Friday but that does not explain anything.

Akhila, in damp shorts and vests and a blue bandana, does not stop to find out what has happened. She is confident of solving the puzzle any moment. Everything that happens in Mumbai has happened before. She walks across the concrete driveway towards Beach Towers even though the behaviour of the residents should have warned her against entering the twenty-storey building.

The possibility of death does not occur to her. It never does. If she is ever in an air crash, she knows, she would be that lone miraculous survivor. She might even save a child. It is not hope, which is merely a conversation with the self. Hope is a premonition of defeat. She knew that even as a little girl who used to wait for her mother to return, wait for days, for weeks. Optimism, on the other hand, is psychosis. Its victims alone know how cheerfully the disease takes them to doom. She has tried but is unable to have complete faith in the view that she will die one day. Science will find a way to make her immortal.

People find immortality amusing because they do not believe they deserve it. Like a gorgeous spouse. But death is merely a technology of the universe, and a time comes, doesn’t it, when a science becomes obsolete.

Apart from immortality she has no grand suspicions about her life. It will be filled with friends, solitary sometimes, and beautiful, of course, as it is for people who run long distances. There might even be greatness at some point, but she is not very clear about the details.

The old woman, in a lovely cotton sari, moves at an excruciating pace. Akhila follows her but it is hard to stay behind; the woman is too slow. It is as though she is lampooning the senior, which is not beyond her, actually.”

She sprints up the stairs to the ninth floor as she usually does. She is still on the first flight of stairs when she hears the lift doors open. It should have been an unremarkable event, but this morning the doors have a loud clear voice and there are echoes. Echoes are rare in Mumbai.

From the lift emerges a tiny ancient woman with a mild hunch, her forearms splayed, holding in each hand a pressed kurta folded on a hanger. The old woman, in a lovely cotton sari, moves at an excruciating pace but manages to get out of the lift a moment before the closing doors can crush her. And she appears to know where she is going with the two hangers. Akhila follows her but it is hard to stay behind; the woman is too slow. It is as though she is lampooning the senior, which is not beyond her, actually. She watches the old woman walk out into the driveway, towards a ring of women guarding the nudes. There, a man has begun to undress, looking valiant in his late decision. He flings his shirt first, then his trousers into the ring of women.

Akhila turns back and runs up the stairs in the unfamiliar silence of vacant homes. The stairway is littered with objects, which is unusual. There are pieces of clothing, eerie dolls, one daft Nokia that surely belongs to a maid, even food. There are footwear and a streak of blood too. So much happens when people flee.

At home, she does the usual stretches on the balcony, watching the Arabian Sea. The sky is a clear blue. Far away a giant cruise ship sails across the bay, like a beautiful novel about nothing. A hectic breeze arrives. The winding bridge over the sea stands like a marvel. Her father hates that bridge. He complains about it every day to her, but she is spared this morning because he is not in town. Something about majestic cable-stayed bridges across shallow seas remind Marxists that they have lost to capitalism and human nature.

She walks to the kitchen, checking her phone, but there are messages that make her stop. They ask if she is alright. Several messages uniformly ask the question, “Did you feel it?” When she sees the Twitter feed she figures that about half an hour ago there were tremors. That explains the neighbours. But the thought of fleeing the building still does not occur to her.

The tremors were mild, but an eighty-year-old, condemned building in Prabhadevi has collapsed. She is drawn to the images of the fallen building. She knows the place, it is not far. There are people still trapped in its debris.

In minutes, she is sprinting down, her spiral curls flailing. She has showered and changed into jeans and a T-shirt that has no message at all to convey.

She runs out of Beach Towers, through a mob of neighbours who are beginning to feel foolish. “She even had a bath,” a woman mutters.

Akhila wonders why they had not stopped her from going up. They may not like her, or they probably thought she knew what she was doing, but still they should have tried to stop her. She likes the idea of a village of people, even if they are nude, asking her to be one of them.

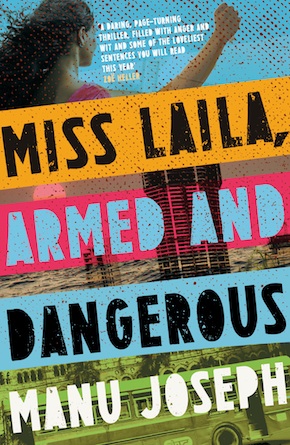

From Miss Laila, Armed and Dangerous (Myriad Editions, £8.99).

Manu Joseph is the author of two previous widely acclaimed and bestselling novels, Serious Men (winner of the Hindu Literary Prize and the PEN/Open Book Award) and The Illicit Happiness of Other People (shortlisted for the Encore Award and the Hindu Literary Prize). A former columnist for the International New York Times, he lives in Delhi and writes for Mint Lounge. Miss Laila, Armed and Dangerous is published by Myriad Editions in paperback and eBook.

Manu Joseph is the author of two previous widely acclaimed and bestselling novels, Serious Men (winner of the Hindu Literary Prize and the PEN/Open Book Award) and The Illicit Happiness of Other People (shortlisted for the Encore Award and the Hindu Literary Prize). A former columnist for the International New York Times, he lives in Delhi and writes for Mint Lounge. Miss Laila, Armed and Dangerous is published by Myriad Editions in paperback and eBook.

Read more

@manujosephsan

Author portrait © Anuradha Kumar