Unfinished business

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“The confusions and contradictions of the story mirror to perfection the confusions and contradictions of civil war.” Words Without Borders

There is a singular sense of feverish neutrality in Thanassis Valtinos’ writing. A cinematic poise, a travelling eye, a dramatist’s instinctive flair for tension, voice, climax, the lull that contains more menace than any thundering explosion; a perpetual game of darkness and light, an omniscient narrator who never divulges all he knows.

Valtinos was born in 1932 in Karatoula, one of the villages comprising the community of Kastri, the epicentre of the events, stories, lives, remembrances of Orthokostá, his 1994 novel which raised a whirlwind of reactions, attracting resounding praise and damning accusations when it was first published. He studied film in Athens then lived in West Berlin as a recipient of a DAAD fellowship, and in the US thanks to the International Writing Program (IWP), experiences which involved both displacement and a better sense of self-awareness; closer focus and a wider perspective.

Valtinos places great emphasis on authenticity, on an unflinching genuineness, on pure, unadulterated art and expression. He is someone who staunchly relishes communities, human give and take, language and echoes, stories. His first two books bear the stamp of all his later work: The Descent of the Nine, written in 1958, then published serially in 1963 in Greece, before it was first published in German in its revised version in 1976, is a polyphonic chronicle of silenced voices, erased viewpoints, thoughts, states of being and the harrowing fluctuations of conscience hounding a band of Antartes (resistance militiamen), seeking an impossible return after the Greek Civil War. His second novel, The Book of Andreas Kordopatis (1964), is a conceit of unmediated realism based on the real-life experiences of an unrepentantly buoyant real person who relished telling dark stories and vibrant anecdotes of his emigration to America to anyone who would listen, embellishing with gusto and the deepest awareness of the human drama and tragedy behind all bravado. Valtinos was one of those who listened to these stories told in a house in Tripoli, who saw into and beyond these tales a larger human narrative.

Far from being a master-puppeteer of his characters, Valtinos is an intriguing combination of the writer who seems to be embedded in every phoneme of his writing and the author who does not, must not exist.”

In almost all of his work, Valtinos stands aside, recording like a Beckettian scribe the voices and their cadences, the sentiments, the causality behind ‘reality’ and its distortions. Far from being a master-puppeteer of his characters, Valtinos is an intriguing combination of the writer who seems to be embedded in every phoneme of his writing and the author who does not, must not exist. That is both his truth and his ploy. His style is sparse and cinematic, stark, robust, attuned to all necessary contrasts, conditions of lighting, narrative movement, frames and seamless montage. At the same time, he can be grandly atmospheric, conjuring up as powerfully the familiar as he does the most transcendentally outlandish. His novels converge with his work for the theatre and the cinema, his collaborations with the dramatist Karolos Koun or the scenarios of the many films he created with one of the most idiosyncratically poetic, quixotic and enigmatic filmmakers, Theodoros Angelopoulos.

Craft faithfully serves content in Valtinos’ case – any minimalism, abstraction or innovation are only finer tools for what he wants to say, for what he wants us to experience and be confronted by. The abstraction in Orthokostá, in terms of the art of fiction, is almost total. Framed by two entries from a travel guide to an idyllic Greek countryside and its sights written by an nebulously serene and elegiac Bishop Isaakios at an unidentifiable time, lies an unsorted, non-linear archive of testimonies, a world of unspeakable experience, a landscape of horror and devastation, as well as an anthology of seemingly prosaic details, such as the loss of a fur-trimmed coat, or a romantic ‘what if’. Bishop Isaakios’ otherworldly descriptions of a place of harmony and beauty clash viciously with a grimmer reality of carnage remembered, relived, recounted, and especially of fragmented memory, identity, a crumbling present and future.

Orthokostá is an exploration of hatred, of the naturalness or not of the so-called instinct of survival. It questions the weight of history, of circumstances, of individual and collective reason, unreason and guilt. The narratives are like the oscillating echoes of souls – buried and unburied alike, innocent and guilty, all equally troubled, unable to find peace or to fall silent. The Greek Civil War – any internecine, fratricidal war – is a perennially unfinished business, an unendurable, festering wound that must, even if it cannot possibly, heal.

Whether the clash was between ideologies or between petty personal spites or interests, the culpability, the necessity for guilt and the imperative for contrition, remains universal, unmitigated and vital. People died indiscriminately – shot as traitors (ideological or national) or had their throats slit with the jagged tops of tin cans simply for being where a victim was savagely sought. The living had to survive somehow, with nightmares and especially with fear, suspicion, persecution and compromise. A mixed sense of weariness and euphoria followed the Civil War in Greece. Newspapers, once bought, were carried home rolled into cylinders to hide the front page, concealing the potential political leanings, intellectual curiosities or loyalties. At the same time, people pent up their feelings of anger, remorse, injustice, despair or disgust, in order to go on, to rebuild from the real ruins that surrounded them.

The powerful distinctiveness of Orthokostá is Valtinos’ strategy of channelling history, human experience, a micro as well as a macro focus through a documentarist narrative – a novel where fiction sustains reality. Through individual witnesses, multiple perspectives, a prismatic overview, the novel attempts to unlock boxes containing palimpsests of memory, to summon ghosts no longer belligerent yet eternally feisty, yearning to divulge truths, untruths, personal suffering, delusion or empty triumph.

Orthokostá is an epic nekyia. The dead speak, on their own or through the living, and will disperse in the end unable to provide a prediction for the future, a solution, an omen or a redeeming prophecy. Their spectral reality is the inescapable bind that has held Greece captive ever since – a prisoner to itself, to its own conscience and self-definition. The countless voices want to speak freely. When the unnamed interviewer intervenes to clarify or goad with questions and corrections, memory becomes fragmentary, resisting, contradictory and self-doubting.

One cannot select the voices of the dead, listen to some while muffling others, and this is a scathing critique, through self-exposure, of fanaticism and partisanship of all hues and colours. It is also a questioning of internationalism, of borderlessness, of a forced effacement of identity. Of what it means to belong, to think freely, to build and safeguard a community. Valtinos retains throughout the sense of rootedness, of an idiom intimately belonging to those sharing blood ties, traditions and a common earth: he too walked the same dusty goat-tracks and shady gorges as the voices speaking.

Orthokostá is a denunciation of horror, of cruelty and savagery, of the stifling of the most basic human instincts – humaneness and understanding. It is a severe j’accuse against a Left that betrayed the liberal principles it claimed to possess, a caustic condemnation of Soviet communism which for Valtinos caused incalculable material and spiritual damage: the “dictatorship of populism” that led 120 artists and writers, including Valtinos, to issue in 1989 a volume of texts in protest against what they saw as the destruction of a world. It is also a furious reprimand against the structures that should have held strong, the upholders of the law – where law there was none. An inevitable thorny subject is British involvement in the tribulations of the Greek Civil War – the irreconcilable, catastrophic rift between the Foreign Office and the SOE, the equivocal, ruinously contradictory decisions, instructions and directives that were issued, enforced, retracted midway, leaving all sides adrift in a storm.

This is a powerful narrative, a novel which by its unorthodox form produces a profound effect on the reader.”

Valtinos never humanises cruelty. Yet he does invite our deepest humanity when he confronts us with it. Every single testimony is a vulnerable confession of endurance, frailty, moral failure or monstrous outright guilt, above all of that Socratic state of aporia – the perplexity that cannot find its way to a solution. Valtinos demands that we share the role of witnessing our own humanity and inhumanity. He throws us right in the middle of this microcosmic labyrinth, from where we must find our own Ariadne’s thread if we are to transcend its death-narrative. As such, his novels, Orthokostá in particular, have the quality of parables: absorbing, multifaceted, urgent, simple and vitally significant.

Valtinos has chiselled himself into one of the most distinctive and defining Greek writers, remaining active, vocal and meaningfully current. In Orthokostá we are faced with the same collapse of values, the disintegration of every familiar fibre, the sense of anguish faced across the world (and in Greece) today. Memory becomes phatic over the most unthinkable atrocities as though in a permanent state of narcosis, which perhaps both distorts and soothes, mollifies an impossible endurance. Orthokostá is against either demonisation or sanctification, and the events and details the narrators choose to focus on reflect the way they have selectively kept memory alive, or show the way an ailing political life has coerced them into editing their own lives.

This is a powerful narrative, a novel which by its unorthodox form produces a profound effect on the reader. As Valtinos insists, the caveat is that it should be read as a novel, a novel of the truth, and not as total history. Nor is it a total representation of the participating sides on a larger scale: this is neither all of Greek Resistance nor the Greek state, it is the microcosm of Kynouria, even as Valtinos confronts us with the terrifying potential that microcosms can have on the world at large. The translation is sometimes uneven and ungainly, yet a feat nonetheless. The attempt to adhere too closely to the idiosyncrasies and stylistic modulations of the Greek vernacular, especially the effort to create an American alternative for the local idiomatic lilts and whimsies, can be awkward, as can be the phonetic transcription of names. Some of Valtinos’ copious puns, double entendres and inherent irony is inevitably lost, yet this is a novel that cannot but lead to more stories, histories, a greater understanding of his country’s culture and trepidations. At its close, one hears an echo of Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio (1919), “it was the truths that made the people grotesques… The moment one of the people took one of the truths to himself, called it his truth and tried to live his life by it, he became a grotesque and the truth he embraced became a falsehood.”

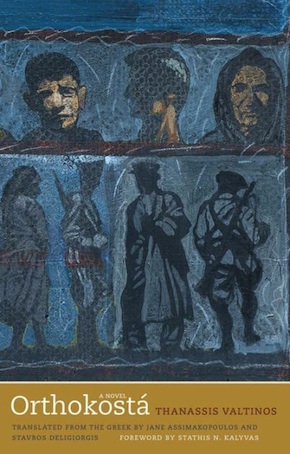

Thanassis Valtinos was born in an Arcadian village in the Peloponnesus in 1932. In addition to his novels, novellas and short stories, he has translated classical Greek drama and written film scripts in collaboration with the late Theodoros Angelopoulos, including the award-winning Voyage to Cythera (1984). Data from the Decade of the Sixties won the National Book Award for Best Novel in 1990 and he has been awarded the Cavafy Prize (2001), the Petros Haris Prize for lifetime achievement (2002), and the Gold Cross of Honour of the President of the Greek Democracy (2003). Orthokostá, translated by Jane Assimakopoulos and Stavros Deligiorgis is published by Yale University Press.

Read more.

Jane Assimakopoulos is an American-born translator living in Greece. As a translation editor she is currently working on a series of books by Philip Roth. Stavros Deligiorgis is a University of Iowa professor emeritus in English and Comparative Literature and the author of many books and articles on literary theory and translation. This edition includes a foreword by Stathis N. Kalyvas, Arnold Wolfers Professor of Political Science at Yale and author of Modern Greece: What Everyone Needs to Know, The Logic of Violence in Civil War and The Rise of Christian Democracy in Europe.

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.