War and imagination

by Jon StallworthyThe Oxford Book of War Poetry has been on active service for thirty years, one hundredth part of the history of warfare to which poets have borne witness. At no point in that history did man’s inhumanity to man generate more eloquent testimony from more poets than in the two world wars of the last century, the Second no less than the First.

To demonstrate the qualitative range of poems prompted by warfare, and to suggest why many fail, a brief case-study of the poetry of the Vietnam War may be instructive. This falls, more starkly than the poems of any earlier conflict, into two principal categories: those written by so-called ‘Stateside’ poets, who never left America, and those of the ‘Vets’ who did. The Stateside poems can themselves be divided into two categories: first, the poetry of first-hand witness to the moral and other effects of the war on America – poems by Allen Ginsberg, for example; second, the poetry of second-hand witness to the war in Vietnam – too much of it like this:

Women, Children, Babies, Cows, Cats

“It was at My Lai or Sonmy or something,

it was this afternoon. … We had these orders,

we had all night to think about it –

we was to burn and kill, then there’d be nothing

standing, women, children, babies, cows, cats. …

As soon as we hopped the choppers, we started shooting.

I remember … as we was coming up upon one area

in Pinkville, a man with a gun … running – this lady …

Lieutenant LaGuerre said, ‘Shoot her.’ I said,

‘You shoot her, I don’t want to shoot no lady.’

She had one foot in the door. … When I turned her,

there was this little one-month-year-old baby

I thought was her gun. It kind of cracked me up.”

This was written by a great poet – Robert Lowell – but I cannot be alone in thinking it is not a great poem. In fact, I think it embarrassing in its blend of black demotic (“I don’t want to shoot no lady”) with the literary (“we hopped the choppers”, and the coy “Lieutenant LaGuerre”). The speaker does not persuade me he mistook the baby (so neatly foreshadowed in his orders) for a gun; or that “It kind of cracked [him] up”. It would tell us – even if we did not know that Lowell never served in Vietnam – that his testimony is second-hand.

In this, it is strikingly unlike his poignant and powerful poem ‘Fall 1961’, which bears first-hand witness to a father’s fear in the midst of the Cuban missile crisis:

All autumn, the chafe and jar

of nuclear war;

we have talked our extinction to death.

I swim like a minnow

behind my studio window.

Our end drifts nearer,

the moon lifts,

radiant with terror.

[ … ]

A father’s no shield

for his child [ … ]

If you feel more for the American father and his child than for the Vietnamese mother and baby, it might be that the poet felt more. Few parents can feel as much pity and terror for a mother and baby seen in a newspaper or a television screen as for a threatened child of their own.

For demographic and social-historical reasons, the ratio of poets to other servicemen and women serving in Vietnam was less than in either world war. Most American intellectuals disapproved of the Vietnam War, and men of military age, particularly white men of military age, could avoid conscription by signing up for university education. And many did. The ratio of Stateside poets to battlefield poets was, therefore, greater than in either world war. There were hundreds of armchair poets pretending, like Lowell, to first-hand witness and/or degrees of moral commitment to which they were not entitled. Few were as good as Lowell, and collectively they deserved the savage rebuke offered by one frontline veteran of the Second World War, Anthony Hecht. Hecht wrote of one such (fortunately unidentified) armchair poet:

Here lies fierce Strephon, whose poetic rage

Lashed out on Vietnam from page and stage;

Whereby from basements of Bohemia he

Rose to the lofts of sweet celebrity,

Being, by Fortune, (our Eternal Whore)

One of the few to profit by that war,

A fate he shared – it bears much thinking on –

With certain persons at the Pentagon.

The knock-out punch of the last line should not blind us to the lightning jab of the first: “Here lies fierce Strephon”. Is he lying in the grave or telling lies, or both? The fury driving this poem is directed, I assume, not at a Stateside poet bearing true witness to the impact of the war on America, but one pretending to first-hand witness of combat in Vietnam. Hecht’s rebuke comes with the moral authority of a poet burdened with the responsibility of bearing witness to the ultimate brutality of the Second World War. He served with the Infantry Division that discovered Flossenburg, an annex of Buchenwald, an experience that changed his life and his poetry.

The charge against a poem like Lowell’s ‘Women, Children, Babies, Cows, Cats’ is that, far from shocking an exposed nerve, it has the numbing effect of second-hand journalism, thereby contributing to the insensitive apathy that enables us to turn, unmoved, from our newspaper’s coverage of disaster to that of a football match. Hecht’s rebuke to “fierce Strephon” points up the further disturbing fact that many of those protesting against the war made money from appearances on “page and stage”.

A problem for many American poets then aspiring to be war poets was that, rightly perceiving it to be an unjust war, they could not participate as servicemen or women; and lacking first-hand experience, could not write convincingly of the war ‘on the ground’. Given some of their trumpeted expressions of moral commitment to the anti-war cause, it is perhaps surprising that none of them felt strongly enough to follow the example of W.H. Auden who, in January 1937, prompted a banner headline of the Daily Worker: “FAMOUS POET TO DRIVE AMBULANCE IN SPAIN.” Explaining his decision to a friend, he wrote: “I shall probably be a bloody bad soldier but how can I speak to/for them without becoming one?”

What do these and other war poems achieve? In that their subject is tragedy, they can – when made with passion and precision – move us (as Aristotle said) to pity and terror; also, I suggest, to a measure of fury.”

One American poet did follow Auden’s example. John Balaban went to Vietnam, but not as an ambulance-driver. He went as a Conscientious Objector to work in an orphanage (for children orphaned by his country’s war), learnt Vietnamese, and stayed after the war to teach in a Vietnamese university. His poems of those years have a fine grain, a specificity of detail, rare in the many poems bearing first-hand witness to an armchair reading of newspapers or the watching of television news. Britain had its ‘Stateside’ contingent of armchair witnesses, and one – so far as I am aware, only one – poet-witness to the war on the ground: James Fenton, the power and poignancy of whose ‘Dead Soldiers’ derives from his first-hand experience of human suffering, sharpened by his deployment of grimly comic detail and a refusal to lapse into mawkish solemnity.

What do these and other war poems achieve? In that their subject is tragedy, they can – when made with passion and precision – move us (as Aristotle said) to pity and terror; also, I suggest, to a measure of fury. And just as we go to a performance of Shakespeare’s King Lear or Britten’s War Requiem for pleasure, we return (or at least I return) to Homer or Owen or Auden for the pleasurable satisfaction that masterpieces afford.

In the short term, one must doubt whether the poems about Vietnam had any significant effect on the course of the war. Certainly the (much better) poems of 1914–18 and 1939–45 had no significant effect on the course of the two World Wars. In the longer term, however, war poems have through history had a significant effect in shaping their societies’ attitudes to warfare. The epics of heroic ages – The Iliad, Beowulf – encouraged the pursuit of glory with their celebration of courage and skilful swordplay. Over the centuries, all that changed.

More British poems of the First World War confirmed “The Old Lie: Dulce et decorum est/Pro patria mori” than challenged it; but, with few exceptions, they have been relegated to the dustbin of history. The poets whose work has survived sing a very different song: one that has played a significant part in introducing subsequent generations to the realities of modern warfare. The poems of the Second World War have had less impact – not because they were less good, but because the reading public has become increasingly attuned to prose, and because the Word (prose as well as verse) has increasingly lost ground to the Image. Our knowledge of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan derived as much from newspaper and television images as from the spoken or written word. Many poems from or about those wars have been published on both sides of the Atlantic and beyond, but all the precedents suggest that the definitive poems from those conflicts have yet to be written – with, I suggest, one exception, Peter Wyton’s ‘Unmentioned in Dispatches’. As and when others emerge, I believe they are as likely to come from the hand of a frontline medic or war correspondent as from a professional soldier.

This is an edited extract from the essay ‘Thirty Years On’ in The New Oxford Book of War Poetry.

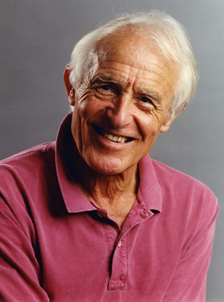

Jon Stallworthy, editor of The New Oxford Book of War Poetry, is a poet and Professor Emeritus of English Literature at Oxford University and a Fellow of the British Academy. Among his other books are critical studies of Yeats’s poetry, and prize-winning biographies of Louis MacNeice and Wilfred Owen. The New Oxford Book of War Poetry is published by OUP. Read more.

Jon Stallworthy, editor of The New Oxford Book of War Poetry, is a poet and Professor Emeritus of English Literature at Oxford University and a Fellow of the British Academy. Among his other books are critical studies of Yeats’s poetry, and prize-winning biographies of Louis MacNeice and Wilfred Owen. The New Oxford Book of War Poetry is published by OUP. Read more.