War stories for children

by Mika Provata-Carlone“Maybe humans aren’t such a terrible animal after all,” reflects a whale that daydreams about aeroplanes in the sky and fatefully falls in love with a Japanese submarine. As the whale insouciantly navigates the sardine-filled waters of nature, the human sea-routes of warships and submarines and the airways of military planes are rife with death and destruction. The innocent whale that thought mating with the deadly submarine would be a union of sublime fertility, comes to a terrible end as it gets blown up by American depth charges – the American radars have mistaken the whale for the enemy vessel, and the whale dies in an ocean “stained red” as though by the setting sun, only it is instead the blood of the whale, the human blood of war and of Japan.

There are animals and humans in each of the stories in Akiyuki Nosaka’s The Whale That Fell in Love with a Submarine, but these are not animal stories or fables. They are the stories of the innocent or of those who cannot understand; and of those who, though understanding, cannot determine either their actions or their reactions to what they witness or must endure.

There are animals and humans in each of the stories in Akiyuki Nosaka’s The Whale That Fell in Love with a Submarine, but these are not animal stories or fables. They are the stories of the innocent or of those who cannot understand; and of those who, though understanding, cannot determine either their actions or their reactions to what they witness or must endure.

The title story sets the tone of unmitigated tragedy and unendurable loss, but also the clear framework of reading and interpretation. Each story is dated 15 August 1945 – the day of Japan’s surrender, marking the end of the war in the Pacific and of World War II. The first story begins with the guiltless whale and a Japanese submarine crew determined to fight to the end – beyond the end proclaimed by their country’s emperor. It concludes with the guiltless dead and the Japanese captain disillusioned: “After the whale had sacrificed itself for their sake, his previous fanaticism had entirely dissipated and he no longer wanted to engage in any more pointless killing. The sunset faded, but the little submarine remained floating there in the red sea”.

The sunset fades as each of these stories is being told: the surrealistic story of a whale falling in love with a human machine, the story of a boy caring for the parrot left to him by his father who is away fighting in the war, the requiem of the mother who turned into a kite, reduced to perfect insubstantiality during the incendiary bombings of Tokyo that claimed 100,000 dead in a single day. There is the archetypal story of the she-wolf that takes under her care a little girl abandoned by the Japanese fleeing Manchuria because she is sick and might infect the others.

The Whale That Fell in Love with a Submarine. Illustration by Mika Provata-Carlone” width=”320″ height=”175″>There are two soldier stories, one of a Japanese pilot, one of an American POW. Both fragile, delicately human, inevitably tragic. The final story is perhaps the one that carries the central question and the dire necessity of hope: it is the magical story of a terrible ending and the dream of a new beginning. After the fire-bombings of March 1945, after weeds have covered the rubble and the charred human bodies, comes a grim lull of famine. A fantastical tree grows in what used to be a great house. Children with famished eyes and unclear minds, with the longing to live, break off and chew the leaves of the tree – and the forgotten deliciousness of food, the unexpected taste of cake, evoke the story. A boy lived there with his mother. The mother fought the war in her own way, through the remembrance of all that was not war, of all that made life a treat before there was war. She wants her son to experience the flavours of long forgotten delights, of foods that will perhaps never be again. With the last thing she can sell she decides to buy a miracle cake – a Baumkuchen, baked layer after layer on a turning spit so that it resembles a veritable tree-log. This cake is sliced minutely, ritually, sacredly day after day, until the mother goes out during an air-raid while the boy remains in the shelter. The mother perishes; the boy survives for some time in a nebulous whirl of memories and delusion, watching a seed grow in the ground, in the company of lizards, mice and “other little creatures”. The boy dies, but the seed becomes the children’s tree, a wondrous Baumkuchen dream tree.

The Whale That Fell in Love with a Submarine. Illustration by Mika Provata-Carlone” width=”320″ height=”175″>There are two soldier stories, one of a Japanese pilot, one of an American POW. Both fragile, delicately human, inevitably tragic. The final story is perhaps the one that carries the central question and the dire necessity of hope: it is the magical story of a terrible ending and the dream of a new beginning. After the fire-bombings of March 1945, after weeds have covered the rubble and the charred human bodies, comes a grim lull of famine. A fantastical tree grows in what used to be a great house. Children with famished eyes and unclear minds, with the longing to live, break off and chew the leaves of the tree – and the forgotten deliciousness of food, the unexpected taste of cake, evoke the story. A boy lived there with his mother. The mother fought the war in her own way, through the remembrance of all that was not war, of all that made life a treat before there was war. She wants her son to experience the flavours of long forgotten delights, of foods that will perhaps never be again. With the last thing she can sell she decides to buy a miracle cake – a Baumkuchen, baked layer after layer on a turning spit so that it resembles a veritable tree-log. This cake is sliced minutely, ritually, sacredly day after day, until the mother goes out during an air-raid while the boy remains in the shelter. The mother perishes; the boy survives for some time in a nebulous whirl of memories and delusion, watching a seed grow in the ground, in the company of lizards, mice and “other little creatures”. The boy dies, but the seed becomes the children’s tree, a wondrous Baumkuchen dream tree.

Akiyuki Nosaka’s early life was as horror-filled, miraculous and surreal as any of these stories… and led to this unique tribute to the impact of war on the experience and the very possibility of childhood – and of humanity itself.”

For Japan, after the war had ended, after “the sunset faded” and the country and its people had “remained there floating in the red sea”, this was the awful moment: what could possibly come next? Akiyuki Nosaka’s early life was as horror-filled, miraculous and surreal as any of these stories, and the passage from shock and annihilating dismay to reckless defiance and transgression in search of answers and a new discourse of existence led to this collection of stories and to the closely autobiographical The Grave of the Fireflies, a unique tribute to the impact of war on the experience and the very possibility of childhood – and of humanity itself. He wrote the latter “in 1967, right in the middle of Japan’s high economic growth years. From my perspective it looked like an abnormal time. I thought the real spirit of humanity was different, and I wanted to depict the idealised humanity of a brother and a sister, or, ultimately, of a man and a woman.”

Material restoration of loss and destruction is meaningless without a place for the stories of devastation – and without a language to speak about the causes of the tragedy, the guilt, the error of horror, as well as the pain. With the stories in The Whale that Fell in Love with a Submarine, first published in Japan in 1980, Akiyuki Nosaka created a book with a unique place in war literature for children. He found a way of telling them about the unknown, the unknowable and what we cannot bear to know, about history as well as humanity, about right and wrong and about what comes after. This is a poignantly gentle book that will never leave the hearts and minds of all who read it, a conscious plea for a different understanding of the world and its values, for other dreams and realities.

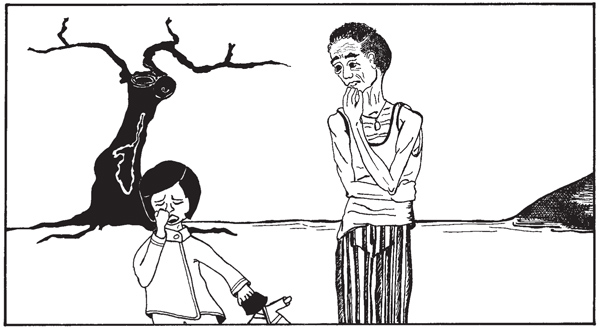

The Whale That Fell in Love with a Submarine. Illustration by Mika Provata-Carlone” width=”320″ height=”180″>Illustrating these stories, now published in a new translation by Ginny Tapley Takemori, meant retrieving images beyond description, full of shattering realism from World War II in Europe as well as in the Pacific. The emaciated mother in the third story was based on the starving mothers in the streets of Nazi-occupied Athens; the American POW on footage from Nazi concentration camps as well as photographs of POWs in Japanese war camps. Every single drawing had to contain what had been really there, and that meant confronting many contradictory feelings of horror and disbelief, seeking a moral basis upon which the illustrations could stand. The subtext of cruelty and unspeakable brutality had to come to the surface in a way that was true and faithful to the victims, all victims, but also endurable. The feeling of these stories is that we must make the unendurable, the unutterable, the utterly inhuman impossible, and it is this feeling that I tried to illustrate.

The Whale That Fell in Love with a Submarine. Illustration by Mika Provata-Carlone” width=”320″ height=”180″>Illustrating these stories, now published in a new translation by Ginny Tapley Takemori, meant retrieving images beyond description, full of shattering realism from World War II in Europe as well as in the Pacific. The emaciated mother in the third story was based on the starving mothers in the streets of Nazi-occupied Athens; the American POW on footage from Nazi concentration camps as well as photographs of POWs in Japanese war camps. Every single drawing had to contain what had been really there, and that meant confronting many contradictory feelings of horror and disbelief, seeking a moral basis upon which the illustrations could stand. The subtext of cruelty and unspeakable brutality had to come to the surface in a way that was true and faithful to the victims, all victims, but also endurable. The feeling of these stories is that we must make the unendurable, the unutterable, the utterly inhuman impossible, and it is this feeling that I tried to illustrate.

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London. The Whale That Fell in Love with a Submarine by Akiyuki Nosaka, translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori and illustrated by Mika Provata-Carlone, is published by Pushkin Children’s Books. Read more.

Read the story ‘The Old She-Wolf and the Little Girl’.