To watch over them

by Leïla Slimani

“A taut and exquisitely written novel that will keep you up all night desperately turning the pages.” Kate Hamer

The baby is dead. It took only a few seconds. The doctor said he didn’t suffer. The broken body, surrounded by toys, was put inside a grey bag, which they zipped shut. The little girl was still alive when the ambulance arrived. She’d fought like a wild animal. They found signs of a struggle, bits of skin under her soft fingernails. On the way to the hospital she was agitated, her body shaken by convulsions. Eyes bulging, she seemed to be gasping for air. Her throat was filled with blood. Her lungs had been punctured, her head smashed violently against the blue chest of drawers.

They photographed the crime scene. They dusted for fingerprints and measured the surface area of the bathroom and the children’s bedroom. On the floor, the princess rug was soaked with blood. The changing table had been knocked sideways. The toys were put in transparent bags and sealed as evidence. Even the blue chest of drawers will be used in the trial.

The mother was in a state of shock. That was what the paramedics said, what the police repeated, what the journalists wrote. When she went into the room where the children lay, she let out a scream, a scream from deep within, the howl of a she-wolf. It made the walls tremble. Night fell on this May day. She vomited and that was how the police found her, squatting in the bedroom, her clothes soiled, shuddering like a madwoman. She screamed her lungs out. The ambulance man nodded discreetly and they picked her up, even though she resisted and kicked out at them. They lifted her slowly to her feet and the young female trainee paramedic administered a tranquilliser. It was her first month on the job.

They had to save the other one too, of course. With the same level of professionalism; without emotion. She didn’t know how to die. She only knew how to give death. She had slashed both her wrists and stabbed the knife in her throat. She must have lost consciousness, lying next to the cot. They took her pulse and blood pressure. They moved her on to the stretcher and the young trainee applied pressure to the wound in her neck.

The neighbours have gathered outside the building. Women, mostly. It will soon be time to fetch their children from school. They stare at the ambulance, puffy-eyed. They cry and they want to know. They stand on tiptoe, trying to make out what is happening behind the police cordon, inside the ambulance as it sets off, sirens screaming. They whisper to one another. Already the rumour is spreading. Something terrible has happened to the children.

It is a handsome apartment building on rue d’Hauteville, in Paris’s tenth arrondissement. A building where neighbours offer friendly greetings, even if they don’t know each other. The Massés’ apartment is on the fifth floor. It’s the smallest apartment in the building. Paul and Myriam built a dividing wall in the living room when their second child was born. They sleep in one half of that room, a cramped space between the kitchen and the window that overlooks the street. Myriam likes Berber rugs and furniture that she finds in antique stores. She has hung Japanese prints on the walls.

Today she came home early. She cut short a meeting and put off the examination of a dossier until tomorrow. Sitting on a folding seat on a Line 7 train, she thought about how she would surprise her children. During the short walk from the metro station, she stopped at a baker’s. She bought a baguette, a dessert for the little ones and an orange cake for the nanny. Her favourite.

She thought about taking the children to the fairground rides. After that, they would buy the food for dinner together. Mila would ask for a toy, Adam would suck on a crust of bread in his pushchair.

Adam is dead. Mila will be too, soon.

***

“No illegal immigrants, agreed? For a cleaning lady or a decorator, it doesn’t bother me. Those people have to work, after all. But to look after the little ones, it’s too dangerous. I don’t want someone who’d be afraid to call the police or go to the hospital if there was a problem. Apart from that… not too old, no veils and no smokers. The important thing is that she’s energetic and available. That she works so we can work.” Paul has prepared everything. He’s drawn up a list of questions and scheduled thirty minutes for each interview. They have set aside their Saturday afternoon to find a nanny for their children.

They want the nannies to see that they are good people; serious, orderly people who try to give their children the best of everything. The nannies must understand that Myriam and Paul are the ones in charge here.”

A few days before this, Myriam was discussing her search with her friend Emma, who complained about the woman that looked after her boys. “The nanny has two sons here, so she can never stay late or babysit for us. It’s really not practical. Think about that when you do your interviews. If she has children, it’d be better if they’re back in her homeland.” Myriam thanked her for the advice. But, in reality, what Emma said had upset her. If an employer had spoken about her or one of her friends in that way, she would have cried discrimination. To her, the idea of ruling a woman out of a job because she has children is terrible. She prefers not to bring the subject up with Paul. Her husband is like Emma. Pragmatic. Someone who places his family and his career above all else.

That morning, they went to the market together, all four of them. Mila on Paul’s shoulders, Adam asleep in his pushchair. They bought flowers and now they are tidying up the apartment. They want to make a good impression on the nannies who will come here. They pick up the books and magazines that litter the floor around and under their bed, and even in the bathroom. Paul asks Mila to put her toys away in large plastic trays. The little girl refuses, whining, and in the end he piles them up against the wall. They fold the children’s clothes, change the sheets on the beds. They clean, throw stuff away, try desperately to air this stifling apartment. They want the nannies to see that they are good people; serious, orderly people who try to give their children the best of everything. The nannies must understand that Myriam and Paul are the ones in charge here.

Mila and Adam take a nap. Myriam and Paul sit on the edge of their bed. Anxious, uncomfortable. They have never entrusted their children to anyone before. Myriam was in her last year at law school when she became pregnant with Mila. She graduated two weeks before the birth. Paul was getting more and more work placements, full of that optimism that had drawn Myriam to him when they first met. He was sure he’d earn enough money for both of them. Certain that, despite the financial crisis, despite budget restrictions, he would forge a career in the music industry.

*

Mila was a fragile, irritable baby who cried constantly. She didn’t put on weight, refusing her mother’s breast and the bottles that her father prepared. Leaning over the crib, Myriam forgot that the outside world even existed. Her ambitions were limited to persuading this puny, bawling infant to swallow a few ounces of milk. Months passed without her even realising. Paul and she were never separated from Mila. They pretended not to notice as their friends got annoyed, whispering behind their backs that a baby has no place in a bar or a restaurant. But Myriam absolutely refused to consider using a babysitter. She alone was capable of meeting her daughter’s needs.

Mila was barely eighteen months old when Myriam became pregnant again. She always claimed it was an accident. “The pill is never a hundred per cent,” she told her friends, laughing. In reality, that pregnancy was premeditated. Adam was an excuse not to leave the sweetness of home. Paul did not express any reservations. He’d just been hired as an assistant in a famous studio, where he spent his days and nights, a hostage to the whims of the artists and their schedules. His wife seemed to be blooming; a natural mother. This cocooned existence, far from the world and other people, protected them from everything.

And then time started to drag; the clocklike perfection of the family mechanism became jammed. Paul’s parents, who had got into a routine of helping them after Mila’s birth, began to spend more and more time at their house in the country, where they were carrying out major repairs. One month before Myriam’s due date, they organised a three-week trip to Asia and didn’t tell Paul until the last minute. He took offence, complaining to Myriam of his parents’ selfishness, their irresponsibility. But Myriam was relieved. She couldn’t stand having Sylvie under her feet. She would smile as she listened to her mother-in-law’s advice; she would say nothing when she saw her rummaging inside the fridge, criticising the food she found there. Sylvie bought organic salads. She made meals for Mila but left the kitchen in a disgusting mess. Myriam and Sylvie never saw eye to eye on anything, and the apartment was filled with a dense, simmering unease that threatened at any moment to break into open warfare. In the end Myriam told Paul: “Let your parents live their lives. They’re right to make the most of their freedom.”

She didn’t realise the magnitude of the task she had taken on. With two children, everything became more complicated: shopping, bath time, housework, visits to the doctor. The bills piled up. Myriam became gloomy. She began to hate going to the park. The winter days seemed endless. Mila’s tantrums drove her mad, Adam’s first burblings left her indifferent. With each passing day, she felt more and more desperate to go out for a walk on her own. Sometimes she wanted to scream like a lunatic in the street. They’re eating me alive, she would think.

She was jealous of her husband. In the evenings, she stood by the door in a frenzy of anticipation, waiting for him to come home. Then she would complain for an hour about the children’s screaming, the size of the apartment, her lack of free time. When she let him talk and he told her about epic recording sessions with a hip-hop group, she would spit: “You’re lucky.” He would reply: “No, you’re the lucky one. I would love to see them grow up.” No one ever won when they played that game.

Even to Paul, she didn’t dare admit her secret shame. How she felt as if she were dying because she had nothing to talk about but the antics of her children and the conversations of strangers overheard in the supermarket.”

At night Paul lay beside her, sleeping the deep, heavy sleep of someone who has worked hard all day and deserves a good rest. Bitterness and regret ate away at her. She thought about the efforts she had made to finish her degree, despite the lack of money and parental support, the joy she had felt when she was called to the Bar, the first time she had worn her lawyer’s robes and Paul had taken a picture of her, smiling proudly outside their apartment building.

For months she pretended she was okay. Even to Paul, she didn’t dare admit her secret shame. How she felt as if she were dying because she had nothing to talk about but the antics of her children and the conversations of strangers overheard in the supermarket. She started turning down dinner invitations, ignoring calls from her friends. She was especially wary of women, who could be so cruel. She wanted to strangle the ones who pretended to admire or, worse, envy her. She couldn’t bear listening to them any more, complaining about their jobs, about not seeing their children enough. More than anything, she feared strangers. The ones who innocently asked what she did for a living and who looked away when she said she was a stay-at-home mother.

*

One day, after doing the shopping in Monoprix on Boulevard Saint-Denis, she realised that she had, without meaning to, stolen a pair of children’s socks. She’d dropped them in the pushchair and forgotten about them. She was a few yards from home and she could have gone back to the shop to return them, but she decided not to. She didn’t tell Paul. It was not an interesting subject, and yet she couldn’t stop thinking about it. After that incident, she would regularly go to Monoprix and hide things inside her son’s pushchair: some shampoo or lotion or a lipstick that she would never use. She knew perfectly well that, if the security guards stopped her, she would just have to play the part of a stressed-out mother and they would probably believe her. There was something hypnotic about those pathetic little thefts. Alone in the street sometimes, she would laugh with the feeling that she was taking the whole world for a ride.

*

When she bumped into Pascal one day, by chance, she saw it as a sign. Her former law-school classmate must not have recognised her at first: she was wearing trousers that were too big for her and an old pair of boots, and she’d tied her unwashed hair up in a bun. She was standing next to the merry-go-round, which Mila refused to come down from. “This is your last go,” she repeated each time her daughter, gripping tightly on to a horse, passed her with a wave. She looked up: Pascal was smiling at her, arms outstretched to signify his joy and surprise. She smiled back, hands clinging to the pushchair handle. Pascal didn’t have much time, but, as luck would have it, his next meeting was close to where Myriam lived. “I have to go home anyway,” she told him. “Shall we walk together?”

Myriam grabbed hold of Mila, who gave an ear-splitting scream. She refused to budge but Myriam stubbornly kept smiling, pretending that the situation was under control. She couldn’t stop thinking about the old jumper she was wearing under her coat and how Pascal must have seen its frayed collar. She frantically rubbed at her temples, as if that were enough to neaten her dry, tangled hair. Pascal seemed oblivious to all this. He told her about the law firm he’d set up with two friends from their year, the difficulties and pleasures of starting his own business. She drank in his words. Mila kept interrupting and Myriam would have given anything to shut her up. Without breaking eye contact with Pascal, she searched in her pockets, in her bag, to find a lollipop, a sweet, anything at all that might buy her daughter’s silence.

Pascal barely glanced at the children. He did not ask their names. Even Adam, asleep in his pushchair, his face peaceful and adorable, did not seem to have any effect on him.

“Here we are.” Pascal kissed her on the cheek. He said, “I’m very glad I got to see you again,” and he went into the building. The heavy blue door slammed shut, and Myriam jumped. She began to pray silently. There, in the street, she felt so desperate that she could have thrown herself to the ground and wept. She had wanted to hang on to Pascal’s leg, to beg him to take her with him, to give her a chance. Walking home, she felt utterly dejected. She looked at Mila, who was playing calmly. She gave the baby a bath and thought to herself that this happiness – this simple, silent, prisonlike happiness – was not enough to console her. Pascal had probably made fun of her. Maybe he’d even called a few of their former classmates to tell them about Myriam’s pathetic life and how she ‘has lost her looks’ and ‘didn’t have the brilliant career we all expected’.

Myriam spoke to Paul about it and she was disappointed by his reaction. ‘I didn’t know you wanted to work,’ he shrugged. That made her furious.”

All night, imaginary conversations gnawed at her brain. The next day, she had just got out of the shower when she heard her phone buzz. A text from Pascal: “I don’t know if you have any plans to become a lawyer again. But if you’re interested, give me a call.” Myriam almost howled with joy. She started jumping around the apartment and kissed Mila, who asked her: “What’s going on, Mama? Why are you laughing?” Later Myriam wondered whether Pascal had sensed her despair or whether, quite simply, he couldn’t believe his luck: bumping into Myriam Charfa, the most dedicated student he had ever met. Maybe he thought he was doubly blessed, to be able to hire a woman like her and to bring her back to the courtroom, where she belonged.

Myriam spoke to Paul about it and she was disappointed by his reaction. “I didn’t know you wanted to work,” he shrugged. That made her furious, more than it should have done. The conversation quickly descended into mud-slinging. She called him an egotist; he described her behaviour as thoughtless. “You’re going to work? Well, that’s fine, but what are we going to do about the children?” he sneered, ridiculing her ambitions and reinforcing the impression she had that she was a prisoner in this apartment.

Once they had calmed down, they patiently studied their options. It was late January: there was no point hoping to find a place in a crèche. They didn’t have any connections in the town hall. And if she did start working again, they would be in the worst of all worlds: too rich to receive welfare and too poor to consider the cost of a nanny as anything other than a sacrifice. This, though, was the solution they chose in the end, after Paul said: “‘If you add in the extra hours, you and the nanny will earn more or less the same amount. But if you think it’ll make you happy…” That conversation left a bitter taste in her mouth. She felt angry with Paul.

*

She wanted to do things right. To reassure herself, she went to a nearby agency that had just opened. A small office, simply decorated, run by two women in their early thirties. The shopfront was painted baby blue and adorned with little gold stars and camels. Myriam rang the bell. Through the window, the manager looked her up and down. She got slowly to her feet and poked her head through the half-open door.

“Yes?”

“Hello.”

“Have you come to apply? We need a complete dossier. A curriculum vitae and references signed by your previous employers.”

“No, not at all. I’ve come for my children. I’m looking for a nanny.”The woman’s face was suddenly transformed. She seemed happy to welcome a customer and equally embarrassed by the contempt she had shown. But how could she have imagined that this tired-looking woman with her bushy, curly hair was the mother of the pretty little girl whining on the pavement?

The manager opened a large catalogue and Myriam leaned over it. “Please, sit down,” she said. Dozens of photographs of women, most of them African or Filipino, flashed past Myriam’s eyes. Mila had fun looking at them all. She said: “That one’s ugly, isn’t she?” Her mother scolded her and, with a heavy heart, returned to those blurred, poorly framed portraits of unsmiling women.

The manager disgusted her. Her hypocrisy, her plump red face, the frayed scarf she wore around her neck. Her racism, so obvious just a minute ago. All this made Myriam want to run away. She shook the woman’s hand. She promised she would speak to her husband about it and she never went back. Instead she pinned a small ad to noticeboards in various local shops. On the advice of a friend, she inundated websites with posts marked URGENT. By the end of the first week, they had received six calls.

She is awaiting this nanny as if she is the Saviour, while at the same time she is terrified by the idea of leaving her children with someone else. She knows everything about them and would like to keep that knowledge secret. She knows their tastes, their habits. She can tell immediately if one of them is ill or sad. She has kept them close to her all this time, convinced that no one could protect them as well as she can.

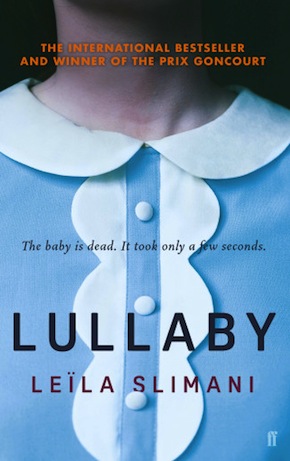

from Lullaby, translated by Sam Taylor (Faber & Faber, £8.99)

Leïla Slimani is a journalist and commentator on women’s and human rights, and was made Emmanuel Macron’s Francophone affairs minister in November 2017. Her first novel Dans le jardin de l’ogre – now published by Faber as Adèle – won Morocco’s Prix La Mamounia in 2015 and her second, Chanson douce, now published as Lullaby, won the Prix Goncourt in 2016. She is also the author of Sex and Lies, a non-fiction book about the sexual desires of Moroccan women, which became a literary sensation in France upon publication. Lullaby is out now from Faber & Faber.

Leïla Slimani is a journalist and commentator on women’s and human rights, and was made Emmanuel Macron’s Francophone affairs minister in November 2017. Her first novel Dans le jardin de l’ogre – now published by Faber as Adèle – won Morocco’s Prix La Mamounia in 2015 and her second, Chanson douce, now published as Lullaby, won the Prix Goncourt in 2016. She is also the author of Sex and Lies, a non-fiction book about the sexual desires of Moroccan women, which became a literary sensation in France upon publication. Lullaby is out now from Faber & Faber.

Read more

Author portrait © Catherine Hélie/Editions Gallimard

Sam Taylor is a Nottingham-born author and translator based in the USA and France. His previous translations include Laurent Binet’s HHhH, Joël Dicker’s The Truth About the Harry Quebert Affair, Riad Sattouf’s The Arab of the Future and the US edition of Maylis de Kerangal’s Mend the Living, published as The Heart.

samtaylorwriter