On the cusp of wherever

by Alex HourstonI am on a beach holiday and it is raining. Still, we sit out, under the umbrellas, because we’re told that it will pass, and there is nothing else to do, and the children are swimming regardless. The rain has delighted them, but I am cold. Everyone around me holds a book, or device. In another month, they might be reading me.

The person on the next-door lounger slags off a brilliant author’s amazing new work.

“It’s so annoying,” she says, as she describes the inspired twist. “I’m gonna skip and see if it gets any better.”

She thumbs through the pages far too fast to actually read.

“Nah,” she says, after a minute; less. “Rubbish.”

Fair enough, of course, she has a right to her view. She chucks the book over the edge of her sun-bed and the spine hits the paving with a crack. It falls open at around the mid-point; the place, I imagine, where she decided that she hated it, and leant into the central crease with her elbow to tell her partner so. He picks the book up from the ground, and tuts.

“Careful,” he says, “It’ll get soaked,” which is something, I suppose.

He drops it into their holdall, though I worry; I’ve been watching them for days and the wet swimmies go in that bag, too.

In a month’s time, I ponder, I will abandon my privacy. It is my choice; I am giving it away. I will expose myself and then ask people what they think, and in doing so, be deserving of everything they say. I must work out the best face to pull as I listen. Should it be the same for bad news and good? Probably not.

The rain does pass. The sun is hot again and the damp stone steams. I remain on my lounger, a few layers lighter. I’ve finished reading something so good that I feel depressed, for various reasons. Next holiday, people may shade their faces with my novel. I will have to keep my distance, if I see it, and tell the children not to shriek, though they are incapable of restraint. They tell everyone who comes to the house: “My mum’s written a book,” and run to pull a copy down from the shelf. I feel a mixture of pride and shame when they do, and a little bit defensive too, under the altered look of whoever now holds three hundred pages of my thoughts in their hands.

Some weigh it, like an object, bouncing it appraisingly as though it’s groceries or a fish they’ve caught, but others just open it up, then and there, and it seems so incredibly rude, what a liberty, what a violation. I find I always know who will do which. I haven’t touched the row of fresh hardbacks that arrived last week in a box, and so the pages give that lovely woody creak as they part for the first time. Then the visitor reads, just a line or two, and looks up at me, and says something like: “Is there much sex?’ or: “I hope I’m not in it,” or: “God. How d’you find the time?” and then I take the book away from them and hurry to change the subject.

Unless, next holiday, not one single person has my book, nor the trip after that, not ever, which would, of course, be worse – far worse – than the previous complaint about privacy.

My family are playing cards, but I’m too wired to join them. I want someone to come over and ask me what I do, so I can tell them: I’m a writer… I feel a fizzing in my chest.”

I’ve had a cocktail, now, a French 75 made with gin and prosecco and lemon. What a thing, and what a thing to be a published author. I can’t wait. We are sitting in the bar because it’s raining again and a man and woman are singing at a piano and usually I would roll my eyes at this but tonight I find I love it. My family are playing cards, but I’m too wired to join them. I want someone to come over and ask me what I do, so I can tell them: I’m a writer. I’ve got a book out next month, actually, seeing as you asked. I feel a fizzing in my chest, though that may be the drink. On my phone I google myself to see if anything has changed. Carefully, though, so the others don’t see. It hasn’t. Oh yes. I have another review on a website. I read it and think it’s OK, though I sense a certain ambiguity of tone. There is a mark, of course, out of five. I’m trying to get a handle on what constitutes a decent score. I try to click on other writers to compare, but the connection drops.

“You know I think we should have a party after all,” I tell my husband. “Who shall I invite? Who’s got a piece of paper?”

I tear out the last page of my daughter’s colouring book and start a list, pushing aside the nuts and mocktails and piles of cards to make more space. I ask my husband his opinion on various names but he seems more focused on their game.

“I thought you said a party was just two hours of showing off?” he says, at last, laughing. He cups the back of a child’s head.

“No. I don’t think that now. I think I should mark it. I’ll only be sorry if I don’t.”

Next morning the ripped-out page is lost and once again, I cannot decide. I know I need a readership. I’m looking forward to a readership. But family and friends? I’ve kept my efforts hidden from them. No one has seen a word, apart from my husband, who said he found the writing good, though perhaps not necessarily for him. That’s fine. His genre is vampires. My sisters feel nervous. We are notorious straight-talkers, but it will be impossible for them to hate it and then tell me so. Will they be forced to lie? We joke about it for now, but I think we’re all concerned that I might be revealed as someone other than I’ve been pretending to be, all these years. That would be weird for everyone.

We ride on donkeys the next afternoon. The temperature rises and we bake ourselves insensible. My children play table-tennis and actual tennis and football on the beach and then suddenly they’ve made friends and in an instant, switch from desperately needing us to witness everything they do, to no longer giving a damn. I feel a little loss and tell myself to try and be more present. That my time at the centre of their lives is short. That my writing can wait. In the hours that their absence affords me, I attempt to imagine every question that I could possibly be asked in a panel-type event, work out the best answers, and then invent a short-hand enabling me to fit all this onto one small page for reference.

We go out on a boat on the final day and there are no turtles but the wind and salt stretches our faces tight and the ocean bellows around us and I rest a hand on each child’s knee and we share these sensations in perfect wordlessness.

Then the holiday is done. I don’t like to fly and the journey home is bumpy, in my view, though when I point this out to the steward after we land, he laughs at me openly and says: “Really? Did you think?” I’m still spaghetti-legged when we leave the plane and as I take a breath of cold damp English air, I experience a flash of perfect perspective. What a brilliant moment, on the brink of things; it all still to come. What a privilege, what impossible luck. And then it’s gone of course, as soon as the car isn’t in the place it’s supposed to be. But later, I try to conjure it and pin it down on the page. It is back. This is my job now, I think.

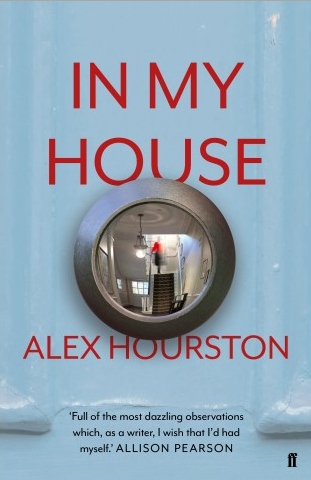

Alex Hourston spent fifteen years writing strategy for advertising agencies, before taking a break to go back to university and her first love, books. She completed a Masters in English and started a PhD, but put it aside when the idea for this novel surfaced. Alex lives outside Brighton with her family, and is now working on her second novel, an exploration of infidelity and emotional inheritance. In My House is published by Faber & Faber in hardback and eBook.

Alex Hourston spent fifteen years writing strategy for advertising agencies, before taking a break to go back to university and her first love, books. She completed a Masters in English and started a PhD, but put it aside when the idea for this novel surfaced. Alex lives outside Brighton with her family, and is now working on her second novel, an exploration of infidelity and emotional inheritance. In My House is published by Faber & Faber in hardback and eBook.

Read more.

@alex_hourston

Author portrait © Jonathan Ring