Why I write

by Guy KennawayWhy do I write? I often ask myself this question. Bottom line is, tough and demoralising as producing books always is, with the countless rewrites and stinging rejections, it is actually much more painful not writing. I always say anyone who can give up writing, does. It’s deep in my soul.

I have two lines to my work: comic fiction and memoir. The only thread that runs through all my books is a desire to make my reader feel joy, and with any luck laugh out loud at the absurdities of life generally and my life in particular. I always think of my reader as wise, worldly and equipped with a sharp sense of humour. If you are not like this, my books are probably annoying and hopefully offensive. My favourite writer is Flaubert, because of his unwavering high regard for his readers. It’s the stuff that Gustave doesn’t need to explain that makes me feel important and sophisticated.

A.A. Gill said where there’s misery there’s comedy, and I have always enjoyed finding genuine laughter amongst the oppressed. Skin diseases, decrepit old age and animals soon to be shot have all been my subjects.

By the standards of many writers, my career has been pretty good. I have always been published, and always by great publishers: I started with Naim Attallah, moved on to Jamie Byng, then to Dan Franklin, and am now with Richard Charkin.

I have had a few books that have brushed the bestseller lists fleetingly, but others that have struggled to tick up decent sales. To me, because I love my books equally, it is a mystery why some are more popular than others.

I believe of course that one day I will hit the jackpot, and maybe that will reawaken the sleeping books of my back catalogue. Meanwhile I stand at the fruit machine of the book trade, and instead of pushing in coins I shove in manuscripts, pulling the handle and hoping for three cherries. But I am keenly aware that we writers have become underpaid, particularly compared to artists, who as far as I can see need only about three ideas to sustain an entire career which keeps them in fine wines, oysters and cash to pay the fabricators who actually do their work for them. I read in the LRB that the publication fee that Jo March earns in Little Women for her short story in 1868 ($100) is the same as you get in 2021.

I always think of my reader as wise, worldly and equipped with a sharp sense of humour. If you are not like this, my books are probably annoying and hopefully offensive.”

But I have found (after some delving) many advantages to not being a massively successful writer. I am relieved of the burdensome task of counting my money, answering adoring fan letters, fielding lucrative sponsorship deals and spending days shopping in New Bond Street. I do not have to find time to cross town to attend dinners with Martin Amis or Edward Enninful. I don’t have to dress up in tails to attend investiture ceremonies at the Palace to receive my MBE. I never have to gently remove the hand of a star-struck woman from my experienced arm. Strangers never take me aside at a party and offer me drugs. Thank God. It is so good. Such an escape.

But I have found (after some delving) many advantages to not being a massively successful writer. I am relieved of the burdensome task of counting my money, answering adoring fan letters, fielding lucrative sponsorship deals and spending days shopping in New Bond Street. I do not have to find time to cross town to attend dinners with Martin Amis or Edward Enninful. I don’t have to dress up in tails to attend investiture ceremonies at the Palace to receive my MBE. I never have to gently remove the hand of a star-struck woman from my experienced arm. Strangers never take me aside at a party and offer me drugs. Thank God. It is so good. Such an escape.

Put it like this: I’ve learnt to live with it. I enjoy the trappings of moderate success. My friends are never jealous, and always encouraging; after all, it is easier to be kinder to someone who has not vaulted up the ladder of success above you. Most importantly, I have never got stuck on a treadmill knocking out the same book as my million-selling debut, with a different title, every year. It has allowed me to follow my star. Even John le Carré could not break out of his genre, try as he did with his sixth book The Naïve and Sentimental Lover in 1971. I happened to be with him in Switzerland when that was published and I could see how concerned he was for it to be a success. He even asked me, a little boy of 11, if I had heard people talking about it and what they had said. Ah, writers. You have to love us. The book wasn’t a success. It fell flat on its face and le Carré went back to driving his spy wagon down those deep ruts.

I don’t like to get an advance from a publisher. I now never take money for something unwritten. That is just a recipe for disaster, though a tempting one. When I did, the advance sat briefly in my current account, and was then spent, and thinking about it became a painful reproach. It is much better to cut a slightly better deal and really enjoy thinking that I actually earn 50p or whatever it may be with each sale. With a big advance sales are basically irrelevant. You are never going to earn more than they gave you. They make sure of that. Also, I don’t like being overpaid for work. If the book doesn’t sell I don’t expect to get rich on the back of some publisher. In addition, I don’t work so hard on a manuscript if its route into print is assured. Being judged by your advance is like being judged by how much you boast. The only thing that matters is the sales I actually make, not dream about. Advances are payday loans that don’t have to be given back. If publishers sent round menacing heavies to the homes of writers to demand from their spouses the 100K the company advanced but which yielded a book that only sold 100 copies, British literature would be a lot more lively.

My friends are never jealous, and always encouraging; after all, it is easier to be kinder to someone who has not vaulted up the ladder of success above you.”

I have never chased sales, and I am certain that even if I had I would not have caught up with them. I plough my furrow across a new field with each book. I have written for my friends and myself, on an almost insanely wide range of subjects, and sort of hoped that others would like what turns us on.

I have never chased sales, and I am certain that even if I had I would not have caught up with them. I plough my furrow across a new field with each book. I have written for my friends and myself, on an almost insanely wide range of subjects, and sort of hoped that others would like what turns us on.

From time to time I get a call from the people in the movies. Morale soars. After a couple of excited conversations, a meeting is arranged. I insist on lunch to establish their style and budget. An intense three-hour meal follows in which we briefly discuss the book, swear eternal friendship, and leave the restaurant clapping each other on the back with tearful farewells and the promise to keep in close touch. Then I never hear from them again.

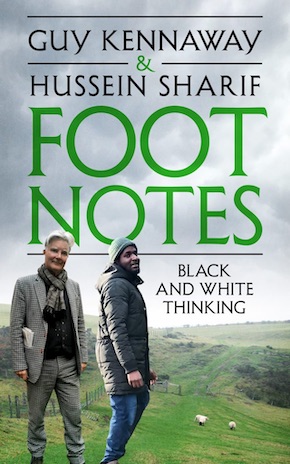

Now I am back at the fruit machine with a book called Foot Notes, about my walk across Britain in the company of a young black Muslim friend of mine. Let’s see how that fares.

This morning, I am about to go and sit with a 14-year-old boy whose severe disability means he cannot talk or move. I shall communicate with him entirely watching his eyes and eyebrows. I am not sure of his cognitive ability. I am finding out about it, because I am writing his biography – bringing his story to the world, and making it meaningful, funny and moving. That’s why I write.

Guy Kennaway is the author of Time to Go, a memoir about assisted dying, The Accidental Collector, a comic novel set in the art world, and Foot Notes: Black and White Thinking, co-authored with Hussein Sharif, a memoir about family, race and a very long walk; all published by Mensch.

Guy Kennaway is the author of Time to Go, a memoir about assisted dying, The Accidental Collector, a comic novel set in the art world, and Foot Notes: Black and White Thinking, co-authored with Hussein Sharif, a memoir about family, race and a very long walk; all published by Mensch.

menschpublishing.com

@guyken

@Menschpublishi1