Where the wise and wild things are

by Mika Provata-CarloneAmanda Brettargh is a quiet torrent of a woman. A conversation with her starts sotto voce, her Australian lilt making you think of vast landscapes and limitless horizons. And this would also sum up exactly her vision of Barnes Children’s Literature Festival, a weekend of talks, activities and workshops dedicated to children, to children’s imagination and to the beauty and power of words.

It is a formidable enterprise, and it has become a pivotal yearly event, all thanks to this one dreamy, determined woman. It was a delight to sit down with her for a very long chat earlier this year and to have the pleasure of interviewing her on the run-up to BCLF 2019.

MP-C: Books are very much part of your life, in every form and shape, in public and in private. Tell us a little bit about your own journey as a reader, as a publisher and now as the lifeforce and creative mind behind the BCLF.

AB: The first love of my life was Enid Blyton! I always loved reading as a child and would have all my dolls and toys lined up and all my little friends. The story is often told in our house about how I would be in the playground rounding up children for story time. Later I would make posters and have invitations with butterflies on them, and I always say if only my parents had let me put on a big books party in our garden none of this would have happened!

The BCLF is a celebration of children as thinkers, as voracious storytellers and story seekers, as thrilling visionaries. How did the idea come about, and why do you think children need such an event? In what ways is it similar to or different from literary events addressed to adults?

I was a journalist for years and then I moved on to public relations where I worked in publishing. I attended literature festivals large and small with my clients and in the adult events I’d look around the room and see them drifting off – literally – I’ve seen them reading the newspaper! But in the children’s events every single child would be transfixed, and the power of live literature was obvious to me. But at a lot of these festivals, the children’s events were almost an afterthought – and still are – and I always thought that they deserved a festival just for them. When I moved to Barnes, I had two seven-month-old twins and I would push my big buggy around beautiful Barnes Pond every day – sometimes several times a day – and I would think “what they really need here is a children’s literature festival!”

This brings us to another crucial question: what is children’s literature? Is it just literature for children, or do you feel it has a character and purpose unique and special to itself? What makes a great children’s author?

It’s a source of great frustration to me that there still persists this strange belief, even among people who should know better, that children’s writing is a lesser literature because it’s not for adults, a kind of literature-lite.

One of the absolutely best parts of my role is that I have the opportunity to read all the books that are submitted for the Festival by publishers each year, and every day I am reminded that the best children’s writing is as sophisticated, as complex, as important and relevant as any piece of celebrated literary fiction. And of course, anyone who has read any book by Michael Morpurgo, Morris Gleitzman, Katherine Rundell, Hilary McKay, Frances Hardinge or Philip Pullman, among so many others, could not possibly argue: “Everything has a meaning. If only we could read it.” – Lyra’s Oxford (His Dark Materials).

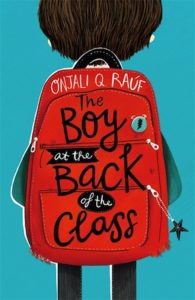

A spectacular example from the books that I have read recently is The Boy at the Back of the Class by the author and activist Onjali Q. Raúf. It’s an ambitious adventure about a nine-year-old boy who arrives at a London primary school after fleeing the war in Syria. It will bring a tear to your eye but there’s plenty to make you smile too; the depth of her empathy is extraordinary. It’s the worthy winner of both the Blue Peter Book Awards Best Story prize and the Waterstones Children’s Book Prize, and we’re honoured to be hosting Onjali as part of our programme for schools this year.

The BCLF is deeply rooted in the Barnes/Greater London community, yet it is certainly not a local event. How has it grown over the years? What are your visions for the future?

It takes a village to produce London’s largest dedicated children’s literature festival! The Festival was created in 2015 by a group of local families, most of us from Barnes Primary School. These days we have been joined by more than 130 volunteers from every Barnes charity, church and community organisation, and book fans from all over London. None of us receives any payment for our time or contributions. We say that we are literacy lovingly wrapped in community.

In our first year we sold about 2,000 tickets to ourselves, to our families and friends and to our schools. Five years later we will sell over 10,000 tickets to families from every London borough and from all over the UK, from Switzerland, Italy, Sweden, Norway, India, the United States and New Zealand.

From foundation our commitment was that every child should have the opportunity to experience the power of live literature, so our plan always included an Education programme of specially curated, curriculum-linked sessions that we would provide free to every state-maintained primary school in London. In 2017, we ran a trial for five hundred local children and this year we will welcome 4,500 pupils from the Richmond, Wandsworth, Hammersmith & Fulham, Kingston and Merton boroughs, and from schools as far away as Walthamstow.

For most of them, this will be their first experience of live literature: a chance to connect with books in a fun way, a small step towards saying yes to new things, to creating new conversations, to climbing higher, to telling their stories differently, to building their futures.

Our target for 2020 is 6,000 pupils; we are working hard all the time towards our goal of reaching every primary school in London.

In what way has the BCLF changed the lives of children (and their parents), of authors and publishers, your own life?

Because Barnes is put on by families, for families, we are one hundred per cent committed to making sure that our family audience has an amazing time during their visit with us, bearing in mind, of course, that families in London, and everywhere else for that matter, come in all different shapes and sizes.

That’s why at Barnes we programme books as film, theatre, music, maths, art, craft, football – whatever it takes really to bring the magic of literacy and literature to the children. And you’ll always find a few special treats at Barnes that you are unlikely to find at festivals anywhere else. This year, for example, we are presenting the London premiere of the outdoor theatre version of Robert Macfarlane and Jackie Morris’s glorious nature book The Lost Words.

Barnes was the first festival to provide specific programming for babies and we’re also committed to enabling children who, for whatever reason, might require a little bit more care for their first festival experience with the introduction of multi-sensory storytelling sessions for those with special and extra needs.

Back in our second year, we had to call the fire brigade down to Barnes Pond to rescue one of our very special visitors from our magnificent trees. Happily the little fellow, together with a book under each arm, was recovered undamaged in the end by the ice cream man using the traditional method of one scoop of chocolate and one scoop of vanilla. “My eyes wouldn’t stop reading,” our adventurer told the crowd, and it was one of those magical moments when after a year of very hard work it all seemed worth it.

If you could invite any living or dead author to the BCLF besides those on your already very impressive list, who would they be and why?

I dream of the day when we’ll welcome Shirley Hughes to Barnes, and I just know how much our audience would love it if David Walliams or J.K. Rowling would accept our invitation.

Do you think we outgrow children’s books? Do you have books from your childhood that are still echoes in your life as a professional, as a private individual, as a mother?

I often think about when I met Max! I was sitting in my primary school library when the librarian gave me a copy of Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak: the fierce text, the dark drawings, so completely different to the candy-coloured world of Enid Blyton or to any book that I had read before. A boy sailing “back over a year and in and out of weeks and through a day and into the night of his very own room” but after all that what he really wanted was “to be where someone loved him best of all.” And his supper! I imagine there’s plenty of truth in this for all of us.

We have a couple of weeks now until the Festival and what else can I say but “let the wild rumpus start!”

Children in the world, children’s books from all over the world. How has a more international perspective in publishing and in readership changed the landscape?

As Atticus says in To Kill a Mockingbird, “You never really understand a person until you consider things from their point of view… until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.” I’m a passionate believer in the transformative power of stories to help children see their world in a different way, to see it as someone else sees it, to walk in their shoes, if you like. And it would seem that children need stories now more than ever to help them make sense of the world that is presented to them through the screen culture, to celebrate the uniqueness of other countries and cultures, to discover our different journeys, and our similarities.

Actually, our favourite book in this house last year was a book in translation: The Murderer’s Ape by the Swedish author Jakob Wegelius, translated by Peter Graves.

The BCLF is the incredible creation of a single visionary woman. It is a little like starting to write a story staring at a very blank page. Tell us about the challenges and the wonders of your own children’s story.

We’ve become London’s largest dedicated children’s literature festival in just five years without any public funding or substantial sponsorship. Unlike the other top tier festivals, Barnes is completely organised and delivered by unpaid volunteers and none of us receives any payment for our time or contribution. We’re for love, not profit, all the way. This means that we can use 100% of the revenue we receive from ticket sales to produce the Festival and the largest free literature festival schools programme in England. Just imagine what we could achieve if we could attract a visionary brand or business who could work with us to help us reach more children, young people and families with the power of live literature than ever before.

If there is one piece of advice or wisdom you would like to share with young and old readers alike, what would it be?

These days I am frequently contacted by people from all over the UK – and from all over the world – saying “I’m a bookshop owner and I’ve been thinking about starting a book festival in my community” or “I’m a librarian and I’d love to organise a book festival at my school,” and to all of them I say: “PUT YOUR POSTER UP!” There’s a lot of hard work involved for sure, but there are some good reads and great times ahead!

Amanda Brettargh is the founder and director of Barnes Children’s Literature Festival.

barneskidslitfest.org

@kidslitfest

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.